During his performance Don’t Make Me Over at the Tufts University Art Galleries on March 15, artist Jeffrey Gibson (Choctaw-Cherokee) deconstructed Dionne Warwick’s 1962 hit song into a strange, cyclical chant, part incantation and part love ballad. The words he sung—”Don't make me over / Now that you know how I adore you” and “Accept me for what I am / Accept me for the things that I do”—were printed on rainbow-hued, floor-to-ceiling curtains that served as a backdrop against which Gibson performed in a costume that transformed him into what he later described as a “radical fairy.” A garment made from layers of iridescent organza obscured his figure, and a cap of small golden bells covered his head. His pants were trimmed with jingles (three-inch-long copper cones worn during pow wow ceremonies and which, the artist later remarked, would traditionally only be worn by a woman), so that each step he took created its own metallic percussion. Nearby, two flat screen televisions displayed recordings of Gibson in a black t-shirt and baseball cap, looking directly out of the frame and singing the lyrics to “Don’t Make Me Over.” Their a cappella melodies acted as back-up vocals that repeated, echoed, and changed keys unexpectedly.

Blending elements of traditional American Indian ceremonies with twentieth-century pop music, generic craft materials, video art, and his own queer identity, Gibson simultaneously honors tradition and breaks from it, creating something radically new and decidedly his own. His performance was staged in connection with A Decolonial Atlas: Strategies in Contemporary Art of the Americas (January 16–April 15, 2018), an exhibition of works that destabilize misrepresentations of indigenous cultures that have been perpetuated since the colonial era. Speaking about his art practice after the performance, Gibson stated: “We need brave people on the front line...negotiating with the world about what it means to be Native American.”

Such a sentiment is central to the art of T.C. Cannon (Caddo/Kiowa, 1946-1978), whose work is featured in the concurrent exhibition T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America, now on view at the Peabody Essex Museum. The exhibition presents a survey of the artist’s oeuvre: a powerful output of paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, and writing created over a period of nearly fifteen years, from early student work produced in the mid-1960s to mature pieces made in the years preceding his death in 1978. Original poems and lyrics printed on the gallery walls underscore his passion for writing and folk music, while a display case of letters and other ephemera provide insight into his time served in the Vietnam War. In short, the exhibition provides a vibrant picture of the cultural moment of the 1960s and 1970s, told through the lens of Cannon’s work.

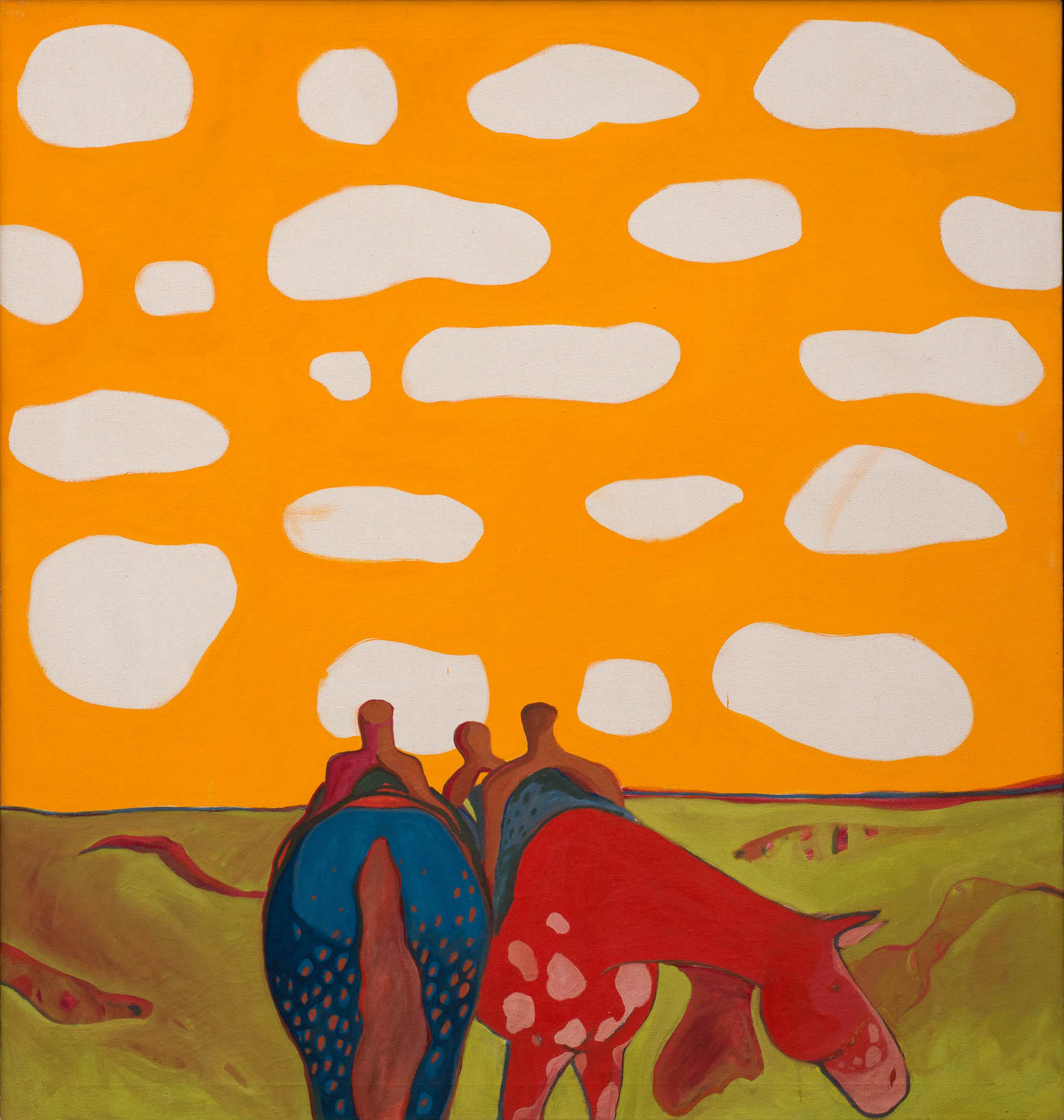

T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), All the Tired Horses in the Sun, 1971–72. Oil on canvas. Tia

Collection. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon.

The multimedia elements of the exhibition and the somewhat overstated exhibition design can be more distracting than enriching. One gallery is dominated by the sounds of a musical recording piped in, but the looping music tends to detract from viewers’ ability to experience the work on their own terms. The entry point to the exhibition is a small square vestibule, each of the four walls serving as a slate for a collage of projected images—of Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Dennis Banks, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the artist himself. The projections are accompanied by an audio recording of a poem written by Cannon. The room aims to situate the viewer in Cannon’s socio-political moment via an immersive, multi-sensory experience, but without any previous introduction to his artwork the room leans more towards disorienting. Why not let his artwork, which so clearly and vividly tells this story, speak for itself?

The following gallery accomplishes this same end, with Cannon’s acoustic guitar on display flanked by two of his early paintings—one a portrait of Bob Dylan, the other a towering canvas titled Mama and Papa Have the Going Home Shiprock Blues (1966). The work features two main figures—a woman wearing sunglasses and wrapped in a blanket, and a man, legs crossed, casually smoking a cigarette—seated on a bench. They float in an undefined space of earthy fields of color, in which opaque patches of olive green brushstrokes abut washes of gold and amber. Ghostly impressions of the two figures repeat across the canvas, and the word “Dineh,” a term for the people of the Navajo Nation, appears in bold stenciled letters in the upper left-hand corner of the canvas.

The painting, which blends figurative expressionism with Pop aesthetics reminiscent of artist Larry Rivers, is often deemed a landmark in Cannon’s career—and in the course of contemporary Native art. Painted while Cannon was studying at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, Mama and Papa certainly had an impact on his fellow students and professors, who at that moment began to question not only what defines American Indian identity, but what constitutes American Indian art?

Much Native art produced in the earlier half of the twentieth century, created under the auspices of newly established government-funded schools and museums, often conveyed a nostalgic or romanticized picture of Native culture frozen in the past. These programs encouraged an idealized vision that was favored by collectors and tourists—scenes of ceremonies, dances, and religious traditions that were, at that point in time, practices largely banned by the government.

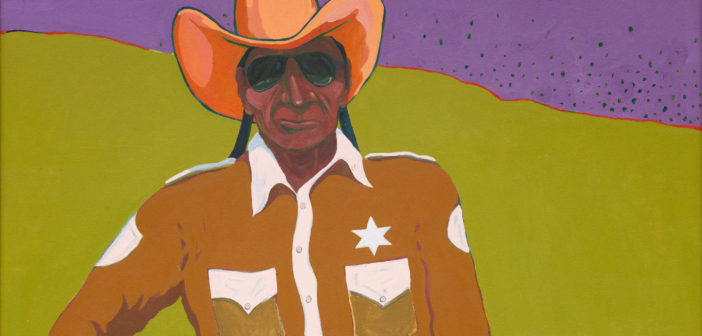

Cannon’s work pushes beyond these strict confines, echoing the mission of the IAIA laid out by its co-founder Lloyd Kiva New: “The Institute assumes that the future of Indian art lies in the Indian’s ability to evolve, adjust, and adapt to the demands of the present, and not on the ability to remanipulate the past.”[1] Cannon’s Native subjects are hard to pin down. They wear aviator sunglasses, western-style button-downs, and army fatigues. They recline on park benches and lawn chairs, carry umbrellas, top hats, and revolvers. But they are just as often portrayed with feathers in their hair, or in ceremonial dress. As in Mama and Papa, elements of popular culture and his Native heritage meld and overlap, suggesting that the two are not mutually exclusive.

T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Indian with Beaded Headdress, 1978. Acrylic on canvas.

Peabody Essex Museum. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Kathy Tarantola.

While Cannon’s paintings depict his experience of contemporary culture, his work does not shy away from historical content. Paintings like Three Ghost Figures (1970) and Small Catcher (1973-78) pay homage to Native ceremony and beliefs. Often he used nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographs of American Indians taken by Edward S. Curtis and William S. Soule as source material for his more historical paintings, which wrest the subjects from their static black-and-white surroundings, recasting them in fluorescent color and imbuing them with life.

History is acknowledged in other ways, too. One of his most dynamic paintings, Beef Issue at Fort Sill (1973), is an arresting combination of vivid color, intense pattern, and minimal texture that addresses the impact of the American Indian Wars on Native lives and culture. The canvas presents two figures in the act of slaughtering a cow, the entrails of which spill out onto neon green blades of grass, as a pair of dogs looks on. One of the figures has paused in the act of cutting to gaze at the viewer, knife gripped in one hand and the other shading her face from the sun. While her eyes are obscured by the shadow of her arm, the dead animal’s large glassy eyes stare eerily out at us, unseeing yet unrelenting. The accompanying label indicates the “beef issue” refers to “a food ration from the U.S. government in the nineteenth century,” in which American Indians received meat—often spoiled—while they underwent imposed assimilation programs. The work is also accompanied by one of Cannon’s poems, titled “Beef Issue,” which begins: “everything must be used / then else returned to the earth / for even now / the grass is black with blood.”

It is not until the early 1970s that Cannon seems to have arrived at this signature figurative style rendered in flat bright color with the occasional textural embellishment. As he moved away from earlier experiments in abstract expressionism, he retained his Pop sensibilities and synthesized aesthetics of western European traditions, such as Fauvism, into his work. His emphasis on bold areas of color encased by dark outlines recalls the Synthetist style of artists like Paul Gaugin and Henri Matisse. Perhaps most influential to Cannon’s style was post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh. Strangely enough, the two artists’ careers and personal lives have some uncanny parallels. Similarly peripatetic, they produced powerful works rife with symbolism during their lifetimes, cut short by untimely deaths in their thirties.

T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Two Guns Arikara, 1974–77. Acrylic and oil on canvas. Anne

Aberbach + Family, Paradise Valley, Arizona. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Thosh Collins

One can spot van Gogh’s influences on Cannon in the bright, lurid colors, the lines imbued with movement, and the way static objects appear to shift and dance unsettlingly in space, as in Washington Landscape with Peace Medal Indian (1976). Working again from nineteenth-century photographs, Cannon depicts a Native leader receiving a peace medal from the government in Washington D.C. He sits in a room defined by a slightly warped linear perspective reminiscent of van Gogh’s The Bedroom (1889), in which the furniture seems in danger of floating away, not tethered to the floor by gravity. Though the figure in Cannon’s portrait rests in a seated position, there is no visible chair or support beneath him; his body appears suspended in air, superimposed against a backdrop of orange curtains patterned with Cannon’s signature ringed circles.

Van Gogh appears again in Cannon’s self-portrait Collector #2 (1973), in which Cannon stands to the right of a copy of the post-Impressionist artist’s Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889). There is confidence and a sense of ownership in Cannon’s stance, with his arms crossed, jaw set, and eyes obscured by sunglasses and wide-brimmed hat; he exudes a cool power. Indeed, a collector manifests a certain kind of authority and influence. She has control over what she selects to surround herself with, and what she rejects—the power of choice, dictated by personal taste and values. By proudly displaying a reproduced van Gogh on his wall, Cannon positions himself as collector rather than collected.[2]

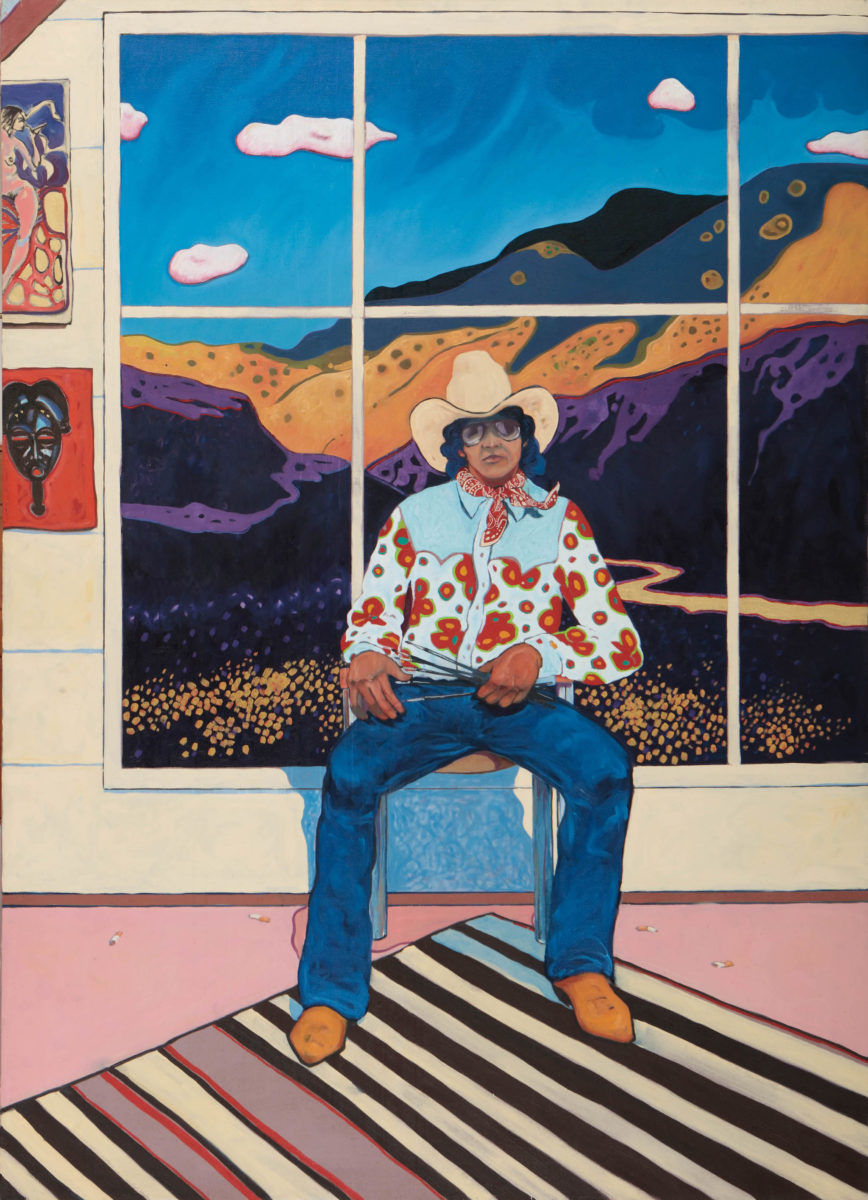

His appreciation for van Gogh might also be tied to his fascination with far-flung cultures; van Gogh looked to the east, specifically to Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, for inspiration, weaving their unique quality of line and color into his work. A few years after Collector #2, Cannon painted Self-Portrait in the Studio (1975), a towering six-foot-tall canvas (presented as a reproduction in the exhibition) that carries on the tradition of artists, from Goya to Brancusi, depicting themselves in their workspaces. Rather than absorbed in his work, Cannon sits in a self-assured pose, gazing out at the viewer from behind his signature aviator sunglasses, a bouquet of paintbrushes clutched in one hand. Although the title indicates he is in his studio, a vast window dominates the background, offering a view onto an almost-psychedelic American landscape: hot orange and violet mountains drip like molten rock against a turquoise sky. The studio floor is covered by a Navajo woven rug (and cigarette butts), and on the wall to his left, a Picasso or Matisse painting hangs above an African mask.

Cannon has surrounded himself with a bricolage of cultural objects, indicating that American, European, and global art traditions, ancient to contemporary, are all part of his personal aesthetic landscape. The key, however, is that this absorption occurred on his own terms. His self-portrait anticipates the words of artist and curator David Garneau, who describes contemporary Indigenous artists as “scouts discovering new pathways of being Native, following ways that are embedded in territory and tradition while also participating with their global relations….[creating]art that gives shape to how we are changing and what it might mean.”[3] In Cannon’s work, the message is not so much one of survivalist mode—a necessary adoption of the dominant white culture in order to endure. Instead, he shifts this narrative, refashioning it into an eclectic worldliness that fed his creativity, but did not overwhelm his identity.

T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Self-Portrait in the Studio, 1975. Oil on canvas. Collection of

Richard and Nancy Bloch. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Addison Doty.

Endnotes:

1. Lloyd Kiva New, in David W. Penney, North American Indian Art (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.: 2004), 205.

2. Ibid.

3. David Garneau, "Contemporary Native Art: Plugged In, Turned On," in Transformer: Native Art in Light & Sound (New York: Smithsonian, 2017), 13.

- Portrait of T. C. Cannon, about 1965. Courtesy of Archives of the Institute of American Indian Arts.

- T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), On Drinkin’ Beer in Vietnam in 1967, after 1978. Lithograph. Private Collection. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Allison White.

- T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Small Catcher, 1973–78. Oil on canvas. Collection of Gil Waldman and Christy Vezolles. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Courtesy of the Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona. Photo by Craig Smith.

- T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), All the Tired Horses in the Sun, 1971–72. Oil on canvas. Tia Collection. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon.

- T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Two Guns Arikara, 1974–77. Acrylic and oil on canvas. Anne Aberbach + Family, Paradise Valley, Arizona. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Thosh Collins

- T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Self-Portrait in the Studio, 1975. Oil on canvas. Collection of Richard and Nancy Bloch. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Addison Doty.

- T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Indian with Beaded Headdress, 1978. Acrylic on canvas. Peabody Essex Museum. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Kathy Tarantola.

- T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Law North of the Rosebud, 1971. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Charles and Karen Miller Nearburg. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Brad Flowers.

- T. C. Cannon (1946–1978, Caddo/Kiowa), Collector #3, 1974. Acrylic and oil on canvas. Collection of Alexis Demirjian. © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photo by Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art.