Conceptual art is often too subtle to reach the edges of our preconceptions, or it is so blatant it prevents our own imaginative leaps. Anila Quayyum Agha’s “Intersections” (2012, laser-cut steel, light bulb), recently on view at the Peabody Essex Museum, lies refreshingly in between. Image itself does the heavy lifting: a steel box suspended from the ceiling is scrolled with Islamic-inspired geometric designs—richly decorative, non-confrontational. At its center, and what brings this artwork alive, is a single light bulb that casts a radius of shadows. One has the sense of being enveloped—even comforted—by patterned golden light.

Anila Quayyum Agha, "Intersections," 2012. Photo courtesy Peabody Essex Museum.

Yet if there is some conceptual ambiguity here, it lies between the artist’s intentions and the experience itself. Agha invites us to grasp the complexity of personal and social conditions through simple beauty, a simplicity that is fluid, graspable, and yet compelling. She intends the viewer to experience a safe space in which, as she states in the wall text, “everybody—people of every denomination, color, race, creed, sexuality” are allowed to “be in that space because it’s a place of beauty.” But it is in the specificity of her experience that we find meaning: generalities lack the power to conjure empathy.

Agha’s story involves the uneasy crossing of boundaries: from Pakistan to the West, as a woman in a male-centric culture to a Muslim in a predominantly Judeo-Christian culture. As Agha puts it in her artist’s statement, “Having lived on the boundaries of different faiths such as Islam and Christianity, and in cultures like Pakistan and the USA, my art is deeply influenced by the simultaneous sense of alienation and transience that informs the migrant experience.” In crossing these borders she has traded one sense of alienation for another. Within Pakistan, women are segregated; in the West, even without the veil, her Muslim status renders her an outsider, particularly in our increasingly xenophobic political climate. But hasn’t this always been the case? Scapegoating “Other” is an enduring fact. Arguably, the only means for the viewer to make these connections is through the artist’s and curator’s explanations, which raises that perennial question: must we have a fuller context in which to appreciate a work of art? Even without this contextualizing, Agha’s work is metaphorically and emotionally powerful.

Viewed as an adjunct to the PEM’s exhibit “MegaCity: India’s Culture of the Streets,” Agha’s installation offers a counterpoint to the narrative of outsider-ness that “MegaCity” (through Dec. 31) explores through two-dimensional works. Collectively, we are invited to see these works in the larger context of South Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

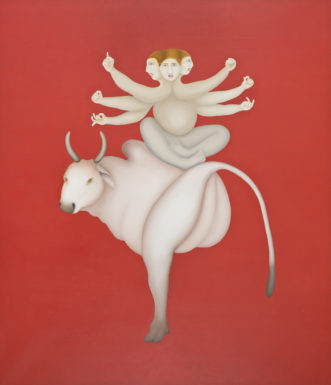

Manjit Bawa, b. 1941 – 2008

"Dharma and the God," 1984

Oil on canvas

85 1/2 x 73 1/4 inches (217. x 186.5 cm)

The Chester and Davida Herwitz Collection, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, E301148

In contrast to “Intersections,” the spare but arresting “Dharma and the God” (1984, oil on canvas) by Delhi artist Manjit Bawa (1941-2008), probes the Hindu principal of universal order. The flesh-toned “bull of dharma” (truth) stands on a single leg supporting an unnamed six-armed goddess, the entire assembly suspended in a red background—in this case, appropriating religious iconography appears to be less personal than philosophical, while both works suggest that “Truth” is in our common humanity. “MegaCity,” on the whole, is more documentary than invitation, providing a narrative specificity to balance “Intersections” in the larger context of the South Asian experience.

In the accompanying short film “Imagine South Asia,” which references the Agha installation, curator Sona Datta describes Agha’s “Intersections” as “an all-embracing space made of shadows and light.” While an apt description, the tapestry of “Intersections,” which Agha calls us to explore, may be unlikely to preach beyond the choir, and yet those visiting the museum who might wander into the grand room and find themselves bathed in a mustard glow have the opportunity to experience, through a specificity of form, an elegant immersion in one spiritual traveler’s take on the experience of Other. That so-called “Other,” in this context the “foreigner,” is not likely to be viewed as a liability. This, perhaps, is what makes “Intersections” such a powerful work: its inherent (and timeless) inclusivity. One hopes that this enduring message finds a permanent home as public art.

“Intersections: Anila Quayyum Agha” was recently on view in the Wheatland Family Gallery of the Peabody Essex Museum, East India Square. Visit www.pem.org for more information.

- Anila Quayyum Agha. “Intersections,” 2012. Photo courtesy Peabody Essex Museum.

- Anila Quayyum Agha, “Intersections,” 2012. Photo courtesy Peabody Essex Museum.

- Manjit Bawa, b. 1941 – 2008 “Dharma and the God,” 1984 Oil on canvas 85 1/2 x 73 1/4 inches (217. x 186.5 cm) The Chester and Davida Herwitz Collection, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, E301148

2 Comments

Great article. Very timely considering the political landscape in which all migrants must struggle and survive.

Thanks so much, Marjie! It is a difficult and volatile time for so many, sadly… They need our compassion for than anything, don’t they?