Tucked between Kevin Beasley’s immersive multi-room solo show and We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85, Caitlin Keogh’s first solo museum exhibition, Blank Melody, greets viewers with a handful of large scale, vibrant paintings.

Installation view, Caitlin Keogh: Blank Melody, May 9 – August 26, 2018, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston. Photo by Charles Mayer. © Caitlin Keogh

From a quick stroll around the gallery, it is almost immediately apparent that this assemblage of works is different from the others that bookend it. Blank Melody is site-specific. Keogh and her collaborators, including assistant curator Jeffrey De Blois, poet Charity Coleman, and artist Graham Anderson, created something of a Gesamtkunstwerk in this space. Though Keogh’s name is the most heavily featured and her work confidently takes center stage, it is clear that this project is also about an organic collaboration between painter and poet. Through these combined efforts, Blank Melody is presented as a chapel to contemplate both visual and written language and a space for two artists to deconstruct and reinterpret ideas of gender, representation, and artistic identity.

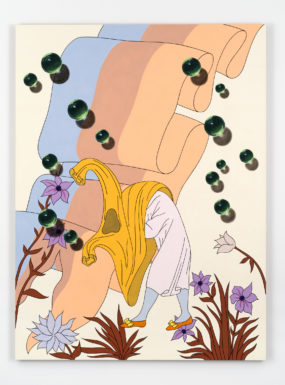

Blank Melody, Cloaked Figure, 2018

Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 63 inches

Wall text makes us aware that this exhibition is “dialogic in form.” The notion of interchange and dialogue between two or more entities seems to be a theme woven through both process and product--the works seem to reference each other, one phrase pointing to an element in a painting and vice versa. In a recent gallery talk, Coleman explained that she wrote Blank Melody (the poem) using Keogh’s paintings for the book Headless Woman with Parrot as visual cues. Immersed in Keogh’s work, Coleman crafted a poem that united Keogh’s visual language with her own voice. Keogh then developed new paintings and text-based work for Blank Melody from Coleman’s interpretive poem.

The space actively invites visitors to stop and look closely. Benches made by Keogh and Graham Anderson populate the room - more than one would usually encounter in a museum or gallery. Fragments of Coleman’s poem, displayed as text cut from paper and mounted on mirror, interrupt the flow from painting to painting, offering us a moment to review the words and see ourselves looking. De Blois noted in the gallery talk that in bringing poetry into this gallery setting, he and the rest of the team considered the idea of being able to “read” the exhibition like a book. Blank Melody presents opportunities for the viewer to slow down and take a seat. Space is made for us to study the elements and attempt to put a narrative together.

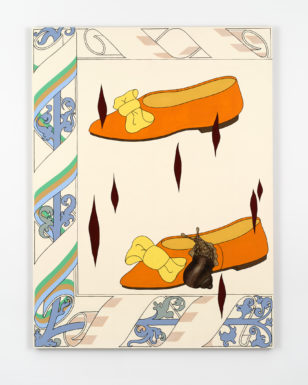

Blank Melody, Tears, Shoes, 2018 Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 63 inches

Keogh’s paintings invite us into a version of her world that references art history, fashion, popular culture. It is difficult to walk away with one coherent understanding - rather, the experience of immersing oneself in the show is dreamlike, like stumbling into a wonderland. It is unsurprising that another source of inspiration for Keogh (in keeping with the theme of a union of word and image) is twentieth-century children’s books. Blank Melody, Cloaked Figure and Blank Melody, Tears, Shoes (both 2018), for example, incorporate a figure and shoes that seem familiar for those who raised on classic fairy tales or the Brothers Grimm. Reading the laminated copies of the poem around the gallery help in deciphering visual elements, but writer and illustrator leave much room for interpretation.

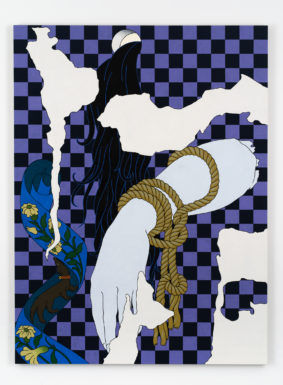

Keogh appears well-versed in the history of European art, referencing the design of illuminated manuscripts or Anglo-Saxon art in paintings such as Blank Melody, Helmet and Blank Melody, Old Wall (both 2018). She pairs these references with imagery of slippers, pearls, ribbons. The hyper-realistic marbles and pearls float on top of the canvas, as if almost on another dimension, providing the sense that these elements are related but not entirely in sync.

Blank Melody, Old Wall, 2018

Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 63 inches

Keogh playfully undercuts any overt symbols of femininity with the inclusion of a slug or “tear” in the canvas. None of the female forms depicted are whole. In some, such as Blank Melody, Limbs (2018), the muse appears to be a mannequin. In others, such as Blank Melody, Cloak (2018) or Blank Melody, Old Wall (2018), Keogh depicts grey-hued, severed limbs weaving through fabric or emerging through barriers, seemingly cracked as if they once belonged to a Greco-Roman statue. The flattened feminine forms fold, wind, twirl and entangle themselves around each other. Surrealism -- particularly its characteristic dream-like and otherworldly nature -- is also a noticeable influence in Blank Melody. Yet, Keogh’s visual style retains a level of ingenuity as it reinterprets imagery familiar to many.

Coleman and De Blois’s gallery talk made clear that Blank Melody is very much an internalized experience--Coleman chose not to read the poem aloud, instead inviting visitors to sit with the words in front of them. Taken together, the works, like topics in a discussion, constantly direct attention to each other or something outside of themselves through partial reference--like when a phrase or word reminds one of an anecdote that then steers the story in a different direction. Walking around the room, bouncing from the laminated copy of the poem to a painting to a text work, Keogh and Coleman’s conversation takes hazy shape. Perhaps even more time in the gallery would have awarded a clearer outcome, but it is very apparent we are just listening in. The dance between Keogh’s strong lines and lively colors and Coleman’s ethereal words plays out as much as we allow it, drawing us deeper into their twin headspace.

Images of paintings courtesy the artist and Bortolami, New York. Photos by John Berens © Caitlin Keogh