The exhibition Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today at the ICA Boston includes the work of sixty artists, collaborations, and collectives. It demonstrates the detachment, escapism, and disenfranchisement of Internet users from various perspectives, as well as the Internet’s ability to bring about empowering change. Using unconventional modes of art-making, including html websites, algorithms, online games, and selfies, artists in this exhibition show how artistic expression changes with new technologies.

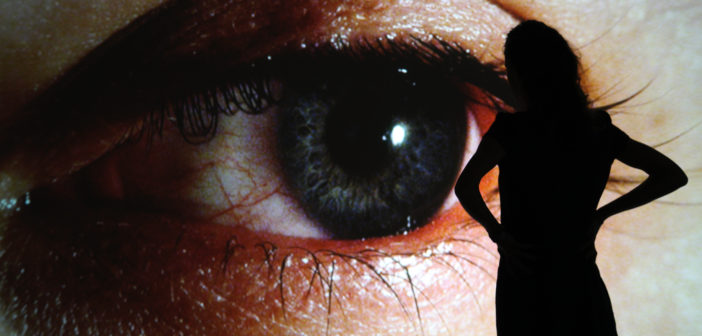

Installation view, Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2018. Photo by Caitlin Cunningham.

Many of the works were conceived in the early 1990s, such as Nam June Paik’s Internet Dream (1994) and Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Surface Tension (1992), and they are extremely prescient in their statements about an Internet age. Paik’s multi-screen installation of brilliantly colored, deconstructed images create patterns that suggest the Internet’s ability to expand communication through a connected network, perhaps metaphorically represented by the multiple, connected televisions stacked upon one another. Surface Tension, a project that was made following the first Gulf War and then reconfigured by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer in 2004 in response to increased governmental surveillance. Hemmer’s video projection combines surveillance technology with the image of a moving eyeball that follows viewers as they walk by the piece. Surface Tension’s implied statement about the sacrifice of privacy of individuals in the hands of more powerful organizations is especially powerful considering recent information leaks from companies like Facebook.

Sondra Perry, Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation, 2016. Video (color, sound; 9:05 minutes) and bicycle workstation. Courtesy the artist and The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Caitlin Cunningham. © Sondra Perry

More contemporary works in the exhibition give a voice to those living within the increased demands imposed by a fast-paced internet age. Sondra Perry’s installation, Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016), incorporates a bicycle workstation found on Amazon, “relaxation” themed music found on Youtube, and a simulation made to resemble the artist. The use of an animated face, rather than video footage of herself, which she often uses in other projects, creates a sense of detachment between the artist and the viewer, who is seated in a “workstation” intended for increased productivity. Perry speaks in the video of both spiritual and moral ideas, such as the just-world hypothesis—a belief that people get what they deserve—an idea that seems absurd in the context of the internet, which can often feel randomized, anonymous, rather than just and personal. She also mentions how our wellbeing correlates negatively with a fast-paced society, which puts less value on our bodies and lives. “We have been told to live up to our potential, but productivity is painful, and we haven't been feeling well,” she tells us.

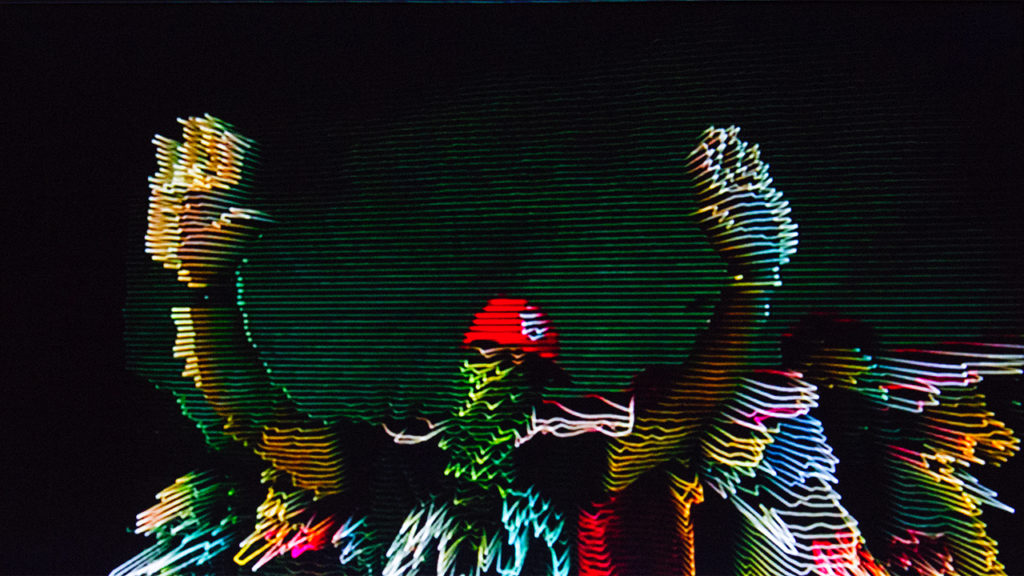

Installation view, Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2018. Photo by Caitlin Cunningham.

There are empowering aspects, however, to an Internet age. Juliana Huxtable’s Untitled (Casual Power) (2015), a visual poem with striking language that celebrates African American culture with phrases like, “WHERE THE ONTOLOGICAL CHAINS OF THE ATLANTIC TRIANGLE REVERBERATE TO SHATTERING POINT IN PATTERNS, BEATS, RHYMES AND TECHNICOLOR INSISTENCES ON A NEW NEW WORLD…” The stream-of-consciousness style of writing suggests the quick flow of information exchanged within our society, and how messages of activism can spread. Untitled in the Rage (Nibiru Cataclysm) (2015), a bold self-portrait, challenges the boundaries of representation with its imaginative use of color. Depicting herself with bright green skin, Huxtable confronts our assumptions about how people “should look” relating to their race. Huxtable uses the word “longing” in Untitled (Casual Power), but I believe it could be applied to this work as well, which so accurately portrays many people’s longing to be seen as more than societally imposed stereotypes. About her representation of self in her work, Huxtable says, “I feel like I am always living as a hybrid of my online presence and my IRL [in real life]presence. I used to feel a bit powerless, and it was actually through playing with my body as an image file that could be manipulated, distorted, rendered, decorated, and placed in new contexts that I came to accept and feel at home in my body as it is currently, but also to imagine how it might move into the future.” This idea of rendering is even more interesting when paired with the sculpture Juliana (2014-15) made by Frank Benson in collaboration with Huxtable and inspired by her self-portrait displayed in the same gallery space. The rendering of her image, which was first a digital 3-D model, then printed, is extremely detailed, a quality that makes one question the lines between our virtual and physical selves. And like other sculptural methods before it, 3-D printing technology can reveal what a society values by what is chosen to be rendered.

HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?, thewayblackmachine (still), 2014–ongoing. Thirty-monitor video installation, approximately 80 x 30 x 10 inches (203.2 x 76.2 x 25.4 cm). Courtesy the artists. © HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?

As Huxtable describes, social media can function as a platform for empowerment personally, but as foreseen in Paik’s Internet Dream, it can also function collectively. Displayed next to Paik’s piece is thewayblackmachine (2014-ongoing) by the collective of artists and thinkers HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN? The thirty-monitor video installation incorporates video footage sourced algorithmically, including tweets from online activists and trending hashtags like #Ferguson, which corresponded to the shooting of Michael Brown and the activism following it. It includes overwhelming footage of media coverage and protesters, like a child holding a sign that says, “Don’t shoot.” It recalls the devastation that one feels while bearing witness to these events on the huge stage of the Internet. But it also gives hope—hope that this increased access also might mean a heightened platform for important ideas and voices.

Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today is on view through May 20.