THE HURT LOCKER AND THE CONTEMPORARY WAR FILM

War films serve many functions in our society. On a superficial level they are entertainment. They follow the conventions of their genre, which were well established in the early days of cinema. We may not view Buster Keaton’s The General (1926) as a stereotypical example of a war film. After all it veers closer to slapstick and situation comedy than the existential moral questioning that later films attempted (I am thinking of The Grand Illusion which is about WWI but certainly foreshadows WWII). Yet even here one can see the foundation of the modern war film. There is conflict – between the North and the South – fighting, and destruction. Behind the narrative of lost and recovered love people die. The conventions of conflict are there. They serve a purpose, either to moralize or to thrill. On a basic level the anxieties of war are an integral part of the human experience and the war film serves to enable us (those of us fortunate enough to not have to experience it) to experience it vicariously. It allows those who haven’t (and probably never will) see for a brief time just what it might be like.

Keaton and Renoir’s films emerged in a historical moment that was haunted by both the past and future experience of war. WWI and II saw death and destruction on levels we can only imagine (just under 20,000 soldiers were killed in the first day of the battle of the Somme in 1916). People knew there were very real consequences to war. This would continue right up to the early nineteen-eighties when the United States still lived with the legacy of conscription. Many people could remember, if not a war, then at least military experience because they had no choice. Elvis Presley was drafted just as his career was exploding. Can you imagine any of the Jonas Brothers surviving boot camp? I think I might actually pay to watch that one. But for a generation that has never had to experience the military or fighting war is a very abstract concept. The current state of the mediated Iraq war (while certainly not as invisible as it was under former President Bush) has placed it far off of our radar. And so when a “war” film centered on the Iraq war emerges it is often met with apathy and tends to fall fairly quickly from the Cineplex.

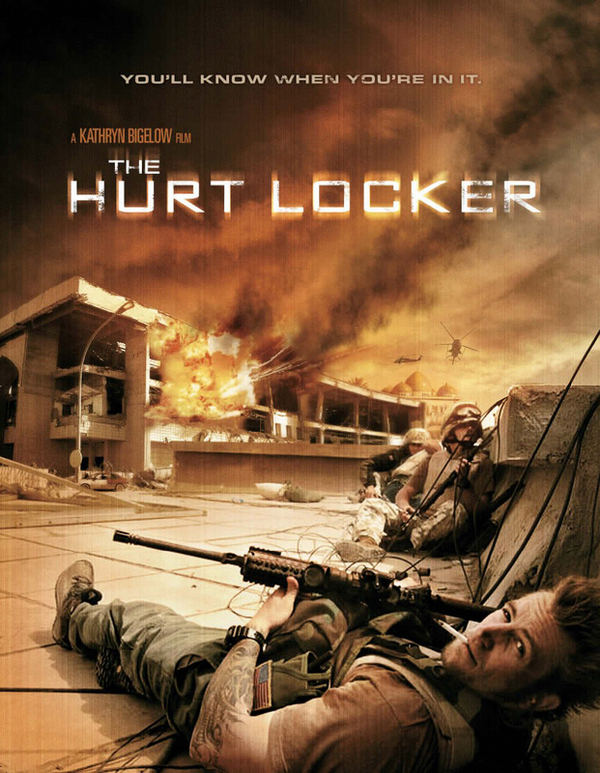

But I hope that something different occurs with Kathryn Bigelow’s new film The Hurt Locker. The Hurt Locker is undoubtedly a war film. But that doesn’t seem to be the point. It certainly takes place in a war zone but what makes this film different is that it is a character study. Ms Bigelow uses the environment of war to explore why some people thrive in these environments. And I don’t mean that they thrive in the sense that they are successful, they thrive in that the situation of war fulfills some part of their personality that the normal world cannot provide. There is something about the adrenalin and rush that being in a war zone provokes that attracts people. This is what her film is about. Unlike De Palma’s Redacted or Paul Haggis’ In the Valley of Elah Bigelow focuses on the individual moments and not the overarching themes of war. This allows her to ultimately make a comment about war without being didactic or resorting to melodrama.

Written by Mark Boal (who also wrote In the Valley of Elah) The Hurt Locker is the story of an elite Army bomb squad unit in Baghdad. Boal was a journalist embedded in a bomb squad and the film’s dialogue and setting have a ring of truth about them that certainly reflects that experience. The main character, Staff Sergeant William James (stunningly played by Jeremy Renner), is the aforementioned thrill seeker. Within minutes of meeting his team James is confronting death head on. He refuses to play it safe and is constantly throwing his body into danger again and again to the consternation of the team that has to back him up. This is perhaps the one complaint I have about the film. While the characters are certainly fleshed out (and convincingly portrayed), Bigelow defaults to genre conventions to identify each team member. They are standard archetypical characters. There is the young member of the team, Specialist Owen Eldridge, who meets with his therapist to help overcome his fear of the war. And there is the jaded, battle scarred veteran, JT Sanborn, who is counting down the days till he ships out. Navigating genre conventions is a strength of Bigelow’s. It serves her well in her other films (Vampires in Near Dark, cops in Point Break) but here it seems to fight against the well rounded characterizations. Do the character conventions allow the actors greater freedom? Perhaps? And it is a minor quibble. It bugged me but I let it go.

What I did like (and was fascinated by) was Bigelow’s use of the body. From the beginning we see the effects of the war and it’s devices on the human form. James’ predecessor is killed within moments allowing us to see the very powerful effects that these hidden bombs on the human body. This sets the audience up for each encounter. We get tense because we know what happens when the bomb blows. In another scene the team encounters a tortured body that James takes for a young boy he had befriended. He discovers numerous bombs inserted into the boy’s body. He places bombs along the top of the corpse planning to blow it up. But he then changes his mind, opens up the sutured body and removes the bombs. It is a horrendous and powerful scene. Not so much horrendous due to the body aspect (although it is pretty graphic), it is horrifying to see the absolute collapse of James when confronted by the boy’s body and subsequent torture. Up to this point we have seen James cool and intellectual in the face of every day dangers and here he has to deal with something outside of his comfort zone. There is no thrill of disarming a device. There is only the trauma of seeing what people are capable of. This is immediately followed by a scene where Eldridge’s therapist (who asked to tag along) is killed by a bomb. So in two back-to-back scenes you have the body as vessel for a bomb and the complete obliteration of a body by a bomb. This serves to destabilize both the audience and the characters. One begins to wonder if Bigelow is going to let anyone survive. She places the literal body is such a tenuous position that you feel that anything is possible.

This is the strength of Bigelow’s film. All war movies are essentially about the body and war’s effects on it (See Johnnie Got His Gun for a film about war and the body) but here she has tied this physicality with the desire of the main character to put his body into danger. Eldridge is seen playing a first person shooter video game as he waits for his therapist yet is frozen in fear when he is forced to shoot another human being. Conversely James is never seen to have doubts about what he is doing. He analyses and keeps the bombs he defuses. This act is everything to him. Putting his body on the line is how he lives. He has nothing else. This point is driven home when we see him interacting with his wife and son back in the United States. Dinner conversation consists of him talking about the various bombs he has worked on. War is simply the opportunity for James to test himself, to see the limits of the body. In this sense The Hurt Locker is not really a war movie. It is a psychological drama that takes place in a war zone. It is an examination of a character that willingly puts himself in harms way. That is the drive. And that is why this film is so powerful. You certainly can’t dismiss the setting and you shouldn’t. However, the role that the war and Baghdad play in this film is not what you would expect. It makes for several great surprises and some powerful moments.

Bigelow has raised the bar on how a war film can function. Her mastery of the genre has allowed her to move away from those conventions and present a film that is experiential and meaningful. Perhaps this will open the door for other filmmakers to approach the Iraq war in a way that allows for an understanding of the experience. Ultimately war films aren’t for those who have been in a war. They are a way for the rest of us to see what it was like. Friends of mine who are veterans of Iraq cannot and will not watch films about it. They have experienced it and films get either too close or not close enough. But we need these films to remind ourselves that people are out there fighting and having these experiences. We need to be reminded that war is not pleasant. Kathryn Bigelow does a pretty good job of it here.

- Promotional poster for The Hurt Locker

- Still from The Hurt Locker, 2009.

- Kathryn Bigelow

"The Hurt Locker" is on view in cinemas nationwide as of Friday, July 10th.

All images are courtesy of the artist and insert venue name.