IRVING HAYNES: ABSTRACTIONS @ NEWPORT ART MUSEUM

Striving to explain to an interviewer why he continued to paint the same subject, an elderly Josef Albers proudly reached back to the exacting standard set at the beginning of modernism:

When I want to speak about why I am doing the same thing now, which is squares, for - how long? - 19 years. Because there is no final solution in any visual formulation. Although this may be just a belief on my part, I have some assurances that that is not the most stupid thing to do, through Cézanne, whom I consider as one of the greatest painters. From Cézanne we have, so the historians tell us - 250 paintings of Mont St. Victoire. But we know that Cézanne has left in the fields often more than he took home because he was disappointed with his work.

The lesson from Cézanne that Albers was so eager for his questioner to understand was one that another teacher and painter, Irving B. Haynes (1927 – 2005), would have recognized and commended. An architect, artist, musician, and RISD professor, Haynes was a man of manifest range, but painting remained his touchstone, a practice of endless visual experiments which he pursued across the years. An exhibition at the Newport Art Museum, Irving B. Haynes: Abstractions, 1960 – 2005, demonstrates his commitment to the patient negotiation between vision and paint through more than four decades worth of rich work. Born in Maine, Haynes came to Rhode Island in 1948 as a transfer student to RISD from Colby College. After earning degrees in painting and architecture, he spent the 1950’s working for a variety of architectural firms by day and playing jazz by nights in area nightclubs. By 1968, the year of the Albers interview, Haynes had his own architectural practice, Haynes and Associates, in Providence. Another career began in 1973, when he started teaching Foundation Studies at his alma mater, assuming an Assistant Professorship in 1980. Haynes’ association with RISD would continue, as he retired from architectural practice in 1990 to concentrate on painting and teaching, becoming a Full Professor in 1997 before retiring in 2005. Painting seems to have been a necessary practice for Haynes throughout all his varied pursuits, something he would seize the chance do under almost any circumstances. All of his paintings were done on paper. Crayon figures into some of the earliest work on display, some of which is so playful it makes one imagine the sticks were taken right from a child’s set. Watercolor and ink recur throughout his practice, though acrylic became Haynes’ favored medium, valued for its quick drying and flat appearance.

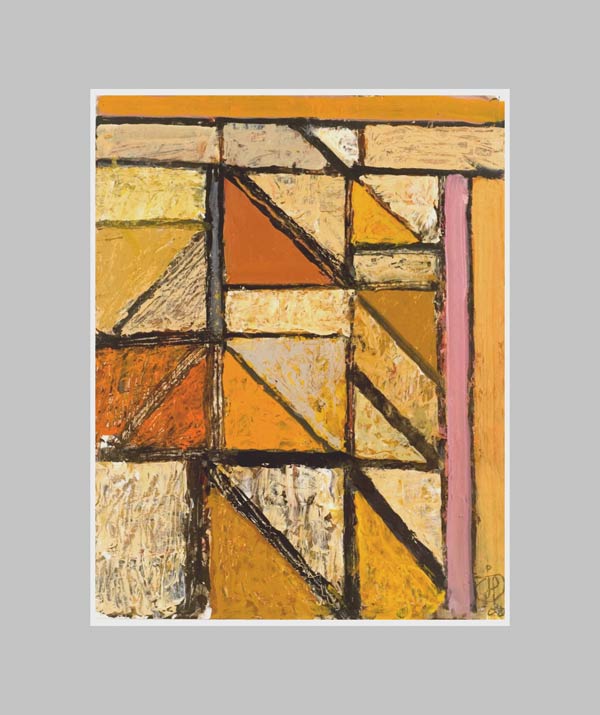

From the start one sees Haynes fully immersed in modernism. Post-Cubist understandings of space are a given, while some paintings, like a 1961 watercolor, engage in a cool biomorphism. Though his artistic sensibility seems to have been most closely attuned to European modernism, several works, including a large 1972 ink on paper, employ a brash Abstract Expressionist scrawl, with thick black lines carving across areas of blue and yellow in a shallow picture plane. A sure feel for color is apparent from the start, but in the paintings from the 1980’s on, Haynes increasingly bore down on the question of structure, with rough squares of color forming loose or implied grids, often interrupted or bisected in turn by black diagonals lines. Like many other abstract painters, Haynes seems to have found the investigation of his chosen structural principles to be freeing rather than restricting: the paintings from these years display a great range of mood, scale, touch, and tone, while almost all building upon the same guiding forms. Iberia, from 2000, to take one example, uses opposing and repeating spiky diagonals to complicate its vertical thrusts, with dusty whites, yellows, and oranges scraped over darker colors predominating the painting while narrow verticals of blue and pink set the range of tones. In a very different mode, China Lake (No. 10), 2003, deploys smooth, placid strokes to create squares and rectangles of cool, verdant greens and blues with only a few variations from its horizontal flow present. Both paintings are built out of the same recognizable process, have a rough grid pattern that visually divides the surface into quadrants and share the same range of shapes, but their achievements are thoroughly distinct. These paintings, like others of Haynes’ later career, and especially his last decade, have a quiet assurance that only comes from a lifetime spent in art.

As the titles of the two paintings might suggest, Haynes’ abstractions are grounded in observations from nature as translated into two-dimensional form. Their essential non-representational character, however, comes across most clearly by the several examples of his photo collages, all dating from about 1995. These consist of photographs of common phenomena—a door frame, a gravel path, woods—cut up, rearranged, and assembled together in grids in a manner to make the everyday strange and allow the underlying character of forms emerge. While not a direct working source for the paintings, they provide a striking example of Haynes at work, investigating and experimenting with the visual world.

The handsomely designed catalog features an essay by Judith Tolnick Champa, formerly of the University of Rhode Island’s Fine Arts Galleries, that skillfully traces the formal development and aesthetic context, visual and musical, of Haynes’ production. I would add one word on the location of the show. The Newport Art Museum’s Griswold House, dating as it does from 1864, is not the first setting one thinks of for abstract painting. The Illgenfritz Gallery, the modern addition where the exhibition hangs, features a more fitting “white cube” look, but the contrast between the two spaces offers perhaps a hint of an appropriate metaphor. Haynes thought his work particularly suited to a domestic space, which Griswold House was, and if its grand scale contrasts with the intimate one of his paintings, the visual stimulation of its rich wood inlays and graceful ornament provide an architectural parallel to his intently structured paintings. Given that Haynes was a modern architect with significant ties to Newport’s historic heritage—his firm headed the restoration of the city’s Trinity Church and Brick Market—as well as a resolutely abstract artist with a teacher’s comfort with the broad range of history, the contrasts and associations feel especially full. One more bit of counterpoint, perhaps, to the compositions on view.

- Irving B. Haynes, Iberia, acrylic on paper, 2000.

- Irving B. Haynes, Untitled, watercolor on paper, 1961.

- Irving B. Haynes, Untitled, ink on paper, 1972.

Newport Art Museum

Irving B. Haynes

Josef Albers interview, 1968 June 22-July 5, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

"Irving B. Haynes: Abstractions, 1960-2005", Newport Art Museum, Newport, RI, April 4-June 7, 2009

All images courtesy the Estate of Irving B. Haynes.