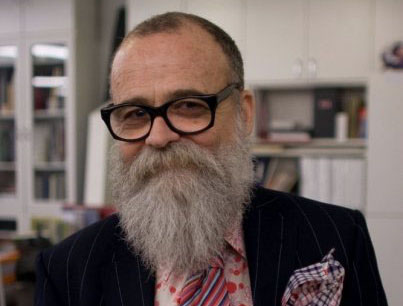

A CONVERSATION WITH AA BRONSON

Big RED & Shiny asked Andi Sutton, a Boston-based performance artist and activist, to interview AA Bronson about activism in the arts. Bronson will be participating in a panel talk as part of the colloquium, "Defining Performativity: Four Perspectives" taking place at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on Friday, April 3rd, 2009.

Andi Sutton: In General Idea, yours was a radical model of living and making art, where the personal was the creative was the political. It seems that you were making visible a new vocabulary of queer culture, and culture in general. From the beginning did you see yourselves as a part of a larger social movement? Outside of one? Creating one in, and through, your life and work? How did this sentiment change, if at all, when you began to be internationally recognized?

AA Bronson: General Idea began in 1969 with a group of us moving into a small house together in Toronto. We all came from beginnings that positioned us as part of the counter-culture that was still coming together across North America: I had been part of a radical commune, published an underground newspaper, and been involved with the beginnings of group and gestalt therapy. Felix had spent a year in Europe and North Africa, traveling in the footsteps of the beat poets. And Jorge had been involved with various experimental theater groups in New York and Vancouver. We saw ourselves as a kind of living theater troupe, moving around the city always in a large group, and indulging in mysterious activities that we saw as performance but which the public probably found inexplicable, like carrying a giant laundry-bag through the financial district. We were very aware of our connections to similar activities going on in other parts of the world and before too long we were in correspondence with people like Ray Johnson in New York, Joseph Beuys in Düsseldorf, and Genesis P. Orridge (of Throbbing Gristle) and Gilbert & George in London. From the beginning we saw our lives and our living as inextricably part of our work, which was itself a kind of reflection on living in an era of mass culture and consumerism. By 1977 we were traveling to Europe on a regular basis, and it was interesting that the Europeans—especially the Italians—saw us as a Marxist group. They were interested in the way that we worked as a group, against the idea of the artist-as-hero, in the fact that our decision-making was built on consensus, and that we were three queer men. This opened our eyes to our own identity: in North America the left-wing thinkers were decidedly uncomfortable with anything queer, and the element of camp in our work made it decidedly unpopular with the straight white men who dominated both the art world and the world of leftist politics. In Europe we were given the freedom to be who we really were, and honored for it. It was understood that despite the use of ambiguity, camp, and humor in our work we were serious about what we did and how we did it.

AS: It is interesting that your strategic uses of humor and camp were not taken seriously in North America – I’m not surprised. It was a strong challenge to the sober and masculine framework of modernism that so much experimental work seemed to be reacting against here. But that you were three queer men… the challenges to this model that your life/work together posed were both literal and symbolic. I think that’s what made the work so potent – and perhaps so instigating.

The work General Idea produced at this time was certainly political – it sounds like these elements were picked up in Europe particularly – but did you also qualify it as ‘activist’? Did this change when you began to focus your practice on the topic of AIDS?

Bronson: General Idea focused on work addressing the subject of AIDS from 1987 through 1994, when my two partners died. We began, because AIDS appeared around us; our best friends were diagnosed. Our earliest AIDS works were based on an AIDS logo we devised, based on the infamous LOVE image of 1967 by Robert Indiana. Remember that this was a time when the president of the United States had not yet uttered the word AIDS in public. We began what was essentially a publicity campaign for a disease. Using the language and methods of the mass media and advertising, we devised projects for posters on the street, the Spectacolor Board on Times Square, billboards, magazine covers, signage on trams and buses, posters in subways, and even displays in museums. Over 70 projects appeared in New York, San Francisco, Toronto, Seattle, Berlin, Florence, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Vienna, and Hamburg.

Finally Felix and Jorge too discovered themselves to be positive. Our life was filled with pills, and doctors. Our projects took the form of pills rather than logos, for example One Year and One Day of AZT, a massive installation of 1825 oversized AZT pills, based on the five-per-day dosage that Felix was on at the time, which showed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In a way, this was not activism in the usual American way. We did not indulge in angry theatrics, but rather presented a quiet steadfast resistance to being invisible. We were more interested in communication than confrontation. At the time that approach was criticized by other activists. But over time, it has become clear that our works continue to broadcast their message for the long term.

AS: I did want to discuss your current projects - where you see yourself now and the relationship of your work to politics and/or activism. I’m curious whether you see a relationship between art and activism and shamanism and healing. Could you comment on whether you see ways that these practices intersect – in your work and also more broadly (in concept or practice)?

Bronson: This is a great question, but I fear I may not have the time to do it justice.

There are several themes that emerge from this question. One is the idea that the artist is engaged in a practice. He is not a producer of collectibles for rich folk; rather, he is engaged in a dialogue. The artist tends to think through making, arranging, and presenting. That's what we do best. And, like writers, our art tends to be our life and our life can often be seen as our work.

Jorge and Felix died in 1994, a few months apart, and both at home, with me the primary caretaker. It was at that point that my activism transformed into shamanism, into healing. Our work had been about AIDS because our lives were dominated by AIDS; but now my life was dominated by the fact of their deaths, and the death of General Idea, and the death of that part of me that went with them. My work, once I was able to begin working again, had to start with what I had: death, mourning, and healing.

In that sense, the two roles of activist and healer have not been so dissimilar. Each has allowed me to engage with the world through a social and political viewpoint. My earliest work after Felix and Jorge died were death portraits of each of them. Since then I have gone on to an actual one-on-one healing practice, which I frame as a performative work: sometimes the gallery becomes the location for healing, with sessions taking place before and after gallery hours, and the space transformed into a kind of spa. More recently my School for Young Shamans returns to my interest in free schools and radical education from the 60s, and weaves in the theme of shamanism.

I am now back at school, working towards my Master of Divinity at Union Theological Seminary, a seminary with a long history of involvement with social justice and radical approaches to feminism and issues of poverty. The place suits me very well, and I am eager to see what I will produce next.

- AA Bronson

- AA Bronson, from the Invocation of the Queer Spirits for Plug In in Winnipeg. Photo by Noam Gonick.

- AABronson, Felix, June 5, 1994, lacquer on vinyl, 1994/99. Bronson’s ‘death portrait’ of Felix.

"Defining Performativity: Four Perspectives" is an all-day colloquium at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on Friday, April 3rd, 2009. The colloquium features a panel talk by AA Bronson, Jose Luis Blondet, curator of the Mills Gallery at the Boston Center for the Arts, and Matthew Nash, publisher of Big RED & Shiny. The keynote address will be given by Ameila Jones, professor and Pilkington Chair in the History of Art and Visual Studies at the University of Manchester.

More information is available here.

AA Bronson images are courtesy of the artist and via Facebook. "Felix" found on Google Image Search.