THOMAS NASON @ THE FLORENCE GRISWOLD MUSEUM

"You talk about the decay of New England. It’s a compost heap."

- Robert Frost to Donald Hall

By the time of his death, the affinity between the prints of Thomas Nason (1889 - 1971) and the poetry of Robert Frost had become such a critical commonplace that the compiler of Nason's collected works felt free simply to match the two: "Frost evoked New England in poetry, Nason in pictures." A shared subject of rural life suggested the connection, while the engravings Nason made for a number of Frost's books published by the Spiral Press cemented it. The Road Less Traveled: Thomas Nason's Rural New England, on view through April 12 at the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut, not far from Nason's longtime home, teases out the equation further, adding new complications. If in 1947 the poet and critic Randall Jarrell could write an essay, "The Other Frost," arguing that this best known of poets was crucially misunderstood by his public, how should we think of the artist that contemporaries so readily identified with him? By showing Nason's work with Frost in both the context of his broader printmaking career and the work of his artistic peers, the exhibition offers some answers, including a re-evaluation of the printmaker's relationship to modernism.

Nason's engraving's for the 1934 reissue of Frost's first book, A Boy's Will, came only three years after he became an artist full time, but were rooted in an apprenticeship of more than a decade. Born in Dracut, MA, the son and grandson of New England ministers, Nason pursued an early office career that took him as far as Asia and Europe, followed by service in World War I. While working in Boston in the years after the war, he became interested in the prints he saw at Goodspeed's Book Shop, the Museum of Fine Arts, and the Boston Public Library, and by 1922 had begun to teach himself wood engraving from nineteenth century sources. The following year his first prints for sale appeared at Goodspeed's. Nason's career seems to have been one of steady growth both artistic and commercial. His earliest prints show a development from a broad technique giving effects more like a woodcut to one marked by a highly expert mastery of his tools reflected in a fine and controlled line. 1931's stark Back Country offers a distillation of key elements of Nason's maturing style in its simplified composition given texture through well-defined gradations of marks. By the late 1930's Nason had become recognized as one of the leading American printmakers, his work sought out by publishers and private clients, with a steady stream of honors coming his way, including election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1955.

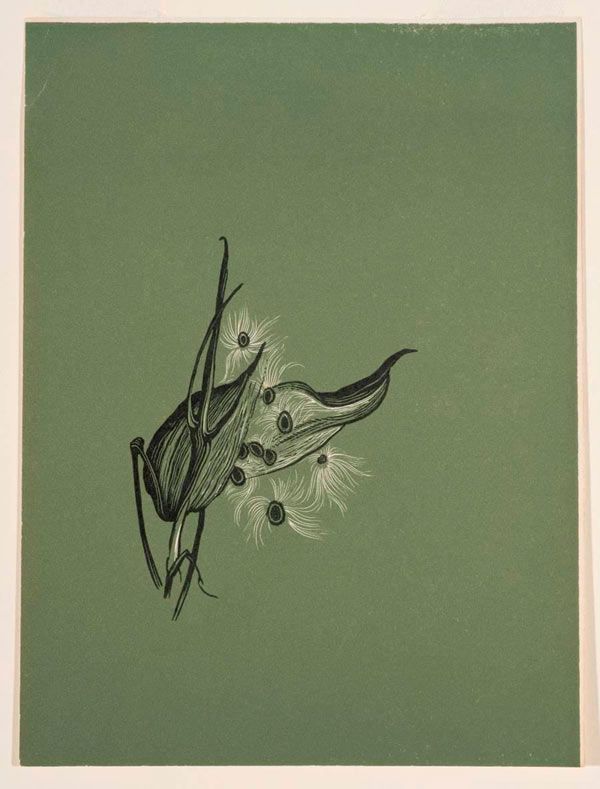

A craftsman's sensibility pervades Nason's work and stands central to evaluating the prints he made for Frost's poems and books. In them Nason demonstrated his design sense, never forgetting that he was creating artwork to accompany and accent the printed page. The selections made by exhibition curator Amanda C. Burdan, Ph.D., from the museum's deep collection of Nason's printing blocks, proofs, and final published works, demonstrate the attention he and the Spiral Press paid toward creating a visual presentation for Frost's poetry. As an artist he was always inclined to work small, but here he made sure to simplify his images to even more economical, suggestive effects. The 1954 cover of From a Milkweed Pod, showing a few seeds drifting free from its single namesake plant, for instance, provided a lyrical image of a literal burst of life, setting the tone for a certain range of receptions for the poetry within. Even more notable in this regard was 1934's Fence-Post and Rail for the title page of A Boy's Will, which became, in the words of the publisher of the Spiral Press, "a kind of Frostian symbol" used for multiple publications, including memorials for both Frost and Nason. In it, a single post with one broken rail stands asserting itself while plants wind around it, an individual caught between civilization and nature, decay and life - a spiritual analog of sorts to the early Frost poems such as "My November Guest" which it accompanied.

Today we stand a long way from the time of Jarrell's two Frosts, one popular, beloved, complacent, and faintly phony, the other a secret hero of the intellectuals, a terrifying poet haunted by despair, isolation, and death. Now the poems on which the latter reputation resided, far from being little known, as Jarrell could argue they were, are accepted as central. That does not mean that those works the critic scorned -- "Birches," say -- are any less a part of what we know about Frost, just that we find ourselves on the far side of a critical journey that's long over. Seeing the prints and chapbooks in cases at the Florence Griswold and returning to their historical moment, however, it's hard not to conclude that Thomas Nason's art played a formative role, along with Frost's own efforts, in building the popular image of the poet and the meaning of his work. If that image was in some ways a disguise, a way of safeguarding Frost for (or from) his public, the fact is not without its irony; for in some respects, Nason, working as a collaborator, was disguising himself as well. Exploring the hidden aspects of his prints -- the other Thomas Nason, if you will -- lead curator Burdan to consider a new topic, the artist's relationship to modernism.

That Nason even had such a relationship is a bold topic that would have surprised his contemporary admirers, one of whom, the artist and writer Clare Leighton, eulogized him after his death as a craftsman who had the misfortune to live into a time "when paintings of soup cans are esteemed highly in the market." The exhibition makes its case on two fronts: first, by noting the change in recent critical understanding of the Regionalist artists with whom Nason has sometimes been grouped -- Thomas Hart Benson, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood, among others, work by whom is on display -- and comparing their own long-unremarked modern aspects to elements that can be found in his work. Nason was not uninterested in modernism -- books from his library on display include a copy of Roger Fry's Vision and Design as well as a volume on the Bauhaus -- nor above employing expressive distortions in his work, as in 1932'sThe Leaning Silo. It remains the case, however, that his exploration of formal modernist effects remained quite restrained, even in comparison with the Regionalists. There's nothing of Rockwell Kent's graphically charged idealism or Benson's wavy plastic contortions in Nason.

It is the exhibition's second argument, a new comparison with Frost, which fits best. Thomas Nason's place in American art, of course, is not the same as that of Robert Frost in poetry, but in some of his works, he did sound similar notes. While informed about modernism, neither artist placed its devices at the center of their practice but instead came closest to its desired extremities of feeling through plainer modes. Nason's independently produced images of abandoned farms and homes wrapped tight in darkness, subjects he returned to frequently, portray a landscape of loneliness. It is perhaps not coincidental that many of these works by Nason seem to come from the 1930's. They seem to speak of the terrible emptiness of lives with, Frost's word's, nothing to look backward to with pride, and nothing to look forward to with hope, so now and never any different.

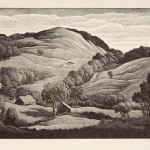

"Pastoral" is a word that one finds frequently used in regard to Thomas Nason's prints, not without reason: a relative late engraving such as 1954's Midsummer depicts a untroubled landscape, New England in a bucolic vision. But the guiding spirit of his art may perhaps be found more precisely in georgics, the adjacent genre that meditates on rural work rather than shepherd's play. Working landscapes not only fill Nason's prints, his own devotion to work remains documented in them. Explanations of the technical side of printmaking too often are a dreary pro forma element of such exhibitions, but in this area as well Burdan has marshaled her resources expertly, providing a clear exposition of Nason's primary techniques of wood and copper engraving. Examples of his blocks, often shown with different prints made from them, make Nason's labor physically present, offering a strong sense of how much patience and dedication went into their creation. It's a fitting tribute to an artist whose dedication to his craft and chosen subjects stood in quiet unity.The Road Less Traveled not only documents Thomas Nason's work, it shows how he made art out of the fertile ground of an older New England in decay.

- Thomas Nason, Illustration for Robert Frost’s From a Milkweed Pod, chiaroscuro wood engraving, 1954.

- Thomas Nason, Midsummer, wood engraving, 1954.

- Thomas Nason, Back Country, wood engraving, 1931.

"The Road Less Traveled: Thomas Nason's Rural New England" is on view January 17 through April 12, 2009 at The Florence Griswold Museum.

All images are courtesy of The Florence Griswold Museum.