Consider the body and its relation to technology and art. Does technology bridge the obtrusive gap between one’s consciousness and the art one creates? The brush, the fragment of charcoal, a stick of graphite, pen, mouse, keyboard, joystick, digital camera, DV camera, Final Cut Pro, Avid, Bolex, Photoshop, AfterEffects -- all are tools; technological “innovations” that enable us to take a dream, an idea, a vision and bring it forth from pure consciousness with the body acting as intermediary. The body enables us to navigate and manipulate these tools. It is in some sense the ultimate tool. We use our physical presence to push, shove, drive, crush, stomp, and smear these mark/image-making technologies in an attempt to conjure up some reflection of what our psyche demands of us. The body does the work of translating. It is the conduit for our desires.

But there is a demarcation between the physicality of pushing or dragging a brush along a surface and the gentle slide of a finger across a mouse pad as one divides a track of audio in two. This demarcation is not set up between what is or is not art. This is not a discursive foray into the pros and cons of digital verses “traditional” art. I am more interested in what technology has done to shift the body’s role in the act of creating.

Imagine yourself in a drawing studio. It is dimly lit with a set of spotlights upon a figure or still life, (this is a scenario from my own studio experience. Feel free to insert your own). Your body is there. You can feel your feet upon the floor, your weight shifting as you find a comfortable stance with your “tools” in easy reach. The figure is before you, at some distance beyond the easel. You know there is a distance between you. The distance has a physical presence. The room is filled with the smell of other people, your charcoal, paint, whatever. The point being that every sense is active: smell, touch, & sound (your breathing, others breathing, perhaps music). You begin interacting with the figure before you by using your tools on the paper/canvas/board. Your weight shifts over and over again as you change tool or change the position of your body in relation to the easel. There is no escaping the fact that you are present in a space. Every shift or stretch of the arm changes the image you are creating. You rub and push the brush, pen, charcoal, oil, graphite until satisfied. You occasionally step away from the easel allowing distance to change your perspective.

Now, you are shooting a video. The video involves you performing an act. The DV camera is your tool. It sits before you on a tripod. The lens is pointed at you. A microphone is mounted on top of it capturing every sound you make. You are alone. You begin performing. You feel your presence in front of the camera. You might even have the LCD screen pointed towards yourself to “see” what the camera sees. You feel the camera looking at you. You let go of self-consciousness and use your body to illustrate feelings or moods. You yell and scream; your body is your tool. As above, your body is interacting with the space, making marks, however, not on a surface held by an easel. You are making marks on a small piece of plastic inside the camera in the form of ones and zeros. Your every movement is being translated into a digital form. You finish performing but this is only the first step. The camera is connected to a computer where the ones and zeros are displayed as video signal. Your further manipulation of the material is now dependant upon your knowledge of computer navigation. It is now about your relationship with the software. Your project either grows or is constrained by your knowledge of video editing software. Let’s presume that you are adept at using the software. You now must spend a set amount of time manipulating a mouse and a keyboard in order to complete your video. You have shifted from an intense physical interaction with a piece of technology to a linear relationship between your mind and the technology. You have to know how to use it to even begin. The digitization will allow you to transform your image, reverse it, segment it, and even freeze it.

With the exception of the hands, from this point forward the body is useless. Your body is hunched in a chair with the eyes affixed to the screen, fingers and hands shifting slightly as desires are raised and satisfied. The hands sit atop a keyboard, arms resting upon a desk. The fingers are splayed across the keys, (if one is less skilled then one hand must rest on the mouse with the other on the keyboard). The distance between your idea and the realization of the idea has collapsed. The distance between you and your image has collapsed. You can zoom in or out of your image in an instantaneous satisfaction of the desire to see more. Through the use of the camera your body has become pure image and your “real” body sitting at the computer simply acts as a vessel for conceptual manipulation of your digital body. For this example I used video with a performance. If the artist is not performing for the camera but shooting, the body is used in a similar fashion to the first example. The camera is held as an extension of the eye with the artist moving and manipulating the frame in an act of composition. With video art that uses appropriated material it is simply a matter of acquiring the footage and beginning the editing. Regardless of how the material is acquisitioned further evolution of the piece is dependant upon technological manipulation. This dependence forces a rethinking of how that art is created. What is occurring in the removal of tactility in creation? The computer and the software have affected a chasm between the artist and the work.

It is this psychological distance that the technology creates and involving the bodies relationship to said technology that I am interested in. On the one hand it is a conflation of distance in what Paul Virilio terms a “time collapse”. There is an instantaneity about art in a digital sphere that allows the mind to focus in a moment of conceptual decision-making and move forward instantaneously towards aesthetic resolution. On the other hand it could be seen as a distancing of oneself from the art. With the technology acting as a device that inhibits “true” art making. This would follow on the belief that to make art one must be literally in the space of art to the complete disavowal of anything digital being art at all. Now it would seem that in the face of contemporary art this perspective would be rather out of date, however one only need to experience a present day art school environment to see that it is consistently promulgated.

As I said above this is not to be a foray into the “is digital art art?” discussion. I believe that technology is forcing us to come to terms with what art making can be. Traditional art making modes are not going to go away. But technology is going to open up the avenues of how it will be made. If a sculptor uses Form-Z to plan out a sculpture, emails the schematic off to a machine that can carve it out in a fraction of the time that the artist could have, does this make the sculpture any less meaningful? The artist was not there in a studio with utensil in hand physically carving away. Yet the object exists as an aesthetic experience for the viewer.

The body has become irrelevant in the construction of a work of art. Technology has become positioned as the interlocutor between the mind and the medium. To some degree it is a realization of Deleuze’s notion of the body without organs. Technology has taken the place of the body. Not completely of course because for the moment most of us are still reliant upon our hands. However, when the majority of the body has been rendered useless, technology has developed to the point where computers can and are manipulated by eye and tongue movement. The body is simply the mind telling the technology what to do and how to do it. It is the flow of pure idea unencumbered by physicality. It is the flow of pure desire. These are the possibilities that technology opens up for artists. Technology is enabling us to literalize our inner visions. It is not pushing aside older forms of art making but it is forcing a re-thinking of what can be art and how one can make it.

- Julia Sher, Security By Julia II, Mixed media, installation view, 1989.

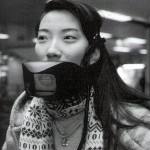

- Krzysztof Wodiczko, The Mouthpiece (Porte Parole), portable audio/video personal instrument, 1993.

- Sue de Beer, still from Hans und Grete, 2002.

Sue de Beer image from "Whitney Biennial 2004" catalog. Published by the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Krzysztof Wodiczko image from "Critical Vehicles: Writings, Projects, Interviews" by Krzysztof Wodiczko. The MIT Press.

Julia Sher image from "Art At The Turn Of The Millenium", edited by Burkhard Riemschneider and Uta Grosenic. Taschen Press.