By KATIE HARGRAVE

Artist Steve Miller's first museum exhibition at Brandeis University's Rose Art Museum in Waltham is certainly a destination, painter Steve Miller's Spiraling Inward is worth the excursion, though don't expect to immediately grasp the visual language Miller has employed in his paintings.

Miller looks to the intersection of art and science, specifically investigating the connections between Nobel Prize winning scientist (and Brandeis Alum) Rod MacKinnon's personal notebooks, blown up images of proteins and molecules, and the history of abstraction in modern art.

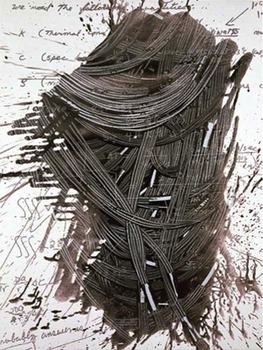

We need the Following Qualities looks like it might be a jumble of wires, or maybe it is muscle fibers, or yarn. Silk-screened on canvas, Dr. MacKinnon's notebook page is obstructed by this confusing protein image, with only the title words and a mess of partial equations showing through. What qualities do we need, Mr. Miller? The work creates a conversation between the neurobiologists who understand these equations, but in their obstruction, he denies the usability of the science. Instead, viewers are left with undeniably beautiful and poetic images.

If Miller is disallowing the scientists to be able to understand this work, then who is it for? Miller claims the work is realistic and representational; these are real images of proteins and real images of MacKinnon's notes. But they also fit ever-so neatly into an art historical narrative about abstraction, borrowing from Pollock's action paintings or the drippyness we find all over painting today.

As a part of the exhibition, The Rose hosted Visualizing Science: Image-Making in the Constitution of Scientific Knowledge, an interdisciplinary symposium surrounding Miller's work.

Several scientists spoke on their personal relationship with aesthetics, from creating 3D models and animations, to decorating the foyer of new scientific buildings with huge edifying images. Miller was sitting directly behind me, and in-between two speakers, I heard him murmur about the constant use of the word "beauty" by these scientists. It was true. For them, Art and Beauty were synonymous; creating an aesthetically pleasing diagram or rendering was akin to creating a work of art. I am not sure about that, and neither was Miller.

Michael Rush, director of the Rose, writes in the catalogue of the similar plight of the scientist and the artist. He claims we're both in the business of discovery, working to understand more about the way our world works. "The most daring move the artist or scientist makes is that first gesture, that irreversible leap into the unknown of their own creativity." [1] The artist and the scientist as Genius? Vasari wrote about this in 1550, the height of the Renaissance, and the idea has surely persisted. Come on, do we really still think that the artist is some sort of all-knowing creative creature tapped in more so than the rest of the world? Professor of the History of Science at Harvard, Peter Galison spoke about the different cultural views of the scientist. He explained that until the 1830's, the scientist too was viewed as Genius; followed by the scientist as diligent worker objectively representing what he sees; and finally the scientist as expert. Pulling from his new book Objectivity (with Lorraine Daston published by MIT press), he noted that these different views are not discrete. Instead, they layer like sedimentary rock, and slowly, hopefully, the genius model will be displaced.

Though a bit lagged behind his model (like more than a century), the art world is mirroring this move. With advanced training and critical thinking, artists are trained in their craft, becoming expert workers rather than being born artistic "rocket scientists".

- Steve Miller, We Need The Following Qualities, dispersion, silkscreen on canvas, 2007

- Steve Miller, Protein #395, 2004

[1] Rush, Michael, ed. Steve Miller: Spiraling Inward. Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University. 2007: iii.

Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University

"Steve Miller: Spiraling Inward " is on view through December 16, 2007 at The Rose Art Museum.

All images are courtesy of the artist and The Rose Art Museum.