A Decolonial Atlas: Strategies in Contemporary Art of the Americas places critical emphasis on the Americas as a region of densely interconnected artistic activity, focusing on artists from Latin and Central America while including Latino, Chicano, and indigenous artists of the U.S. as well as Latin American artists living abroad in Europe. At one time associated with revolutionary independence movements, nationalism in Latin America has long been linked to state repression that works in cooperation with imperialist interests. Thus a decolonial atlas of the Americas is one that undoes strict geographic boundaries and their ideological implications.

Instead of delineating works by region or country, the exhibition is divided into four overlapping themes, all of which are dominated by strategies of embodiment. The artists themselves or their subjects become bodily surrogates for fraught social and political issues. Everywhere one looks in the exhibition, bodies are present through photography and video, ritually enacting complex social histories or hybrid identities.

Strategies of collage, montage, and layering also dominate as a means of disrupting official histories and representations. The most obvious form this takes is the juxtaposition of what we would consider “traditional” cultural forms with contemporary artistic strategies. Eamon Ore-Giron’s canvases, the only paintings in the exhibition, offer the most simplified version of this juxtaposition. In a sort of stylized Meso-Futurism, they blend vaguely pre-Columbian design with high-modernist geometric abstraction in a gesture reminiscent of earlier twentieth-century bids for legitimacy through the marriage of international modernism and a self-consciously local vernacular.

Martine Gutierrez, Maria, Cakchiquel, 2016. C-print mounted on Sintra. © Martine Gutierrez, Image Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE, New York.

This stands in contrast to much of the work presented in the first section of the exhibition, “Recasting Indigeneity,” focused on the politics of indigenous representation. Jeffrey Gibson’s video performance and Martine Gutierrez’s photographic portraits both use queer strategies of performance and costuming to embody difficult tensions at work in hybridized self-representation. As queer and transgender artists with indigenous roots, their use of traditional signifiers of indigenous femininity become neither reductive nor repressive, but rather act as the means by which they create space for themselves within a culture doubly hostile to their presence.

Similarly, Raul Baltazar’s multimedia wall piece Botanica Deer, House, Coyote, Conejo (2017) embraces stereotypes of Southwest Indian visual culture through an assemblage of everyday objects and tchotchkes loosely associated with indigenous culture in the popular imagination. Balthazar’s assembled ritual objects reclaim the dominant culture’s cheap romanticizing of indigeneity as a commodity, slyly transforming these kitsch objects back into the thing they point to. Hybridity here is not the marriage of Western “high” culture and non-Western “tradition,” but of two seemingly incompatible notions of indigeneity—lived and romanticized—that nevertheless cohabitate.

The section “Dislodging Time” features works that present multiple overlapping conceptions of time, placing the Western, linear framework of history in dialogue with cyclical time that points to both pre-modern and contemporary conditions. Naufus Ramírez Figueroa’s video Breve Historia de la Arquitectura en Guatemala/ A Brief History of Architecture in Guatemala (2010-13) is a prominent inclusion. Figueroa is one of the better-known artists from the emerging Guatemalan performance art scene, a small but vital community that combines local performance traditions with internationally inflected avant-garde strategies. Figueroa’s video nods to Bauhaus artist Oskar Schlemmer’s 1922 Triadic Ballet, with three nude performers donning boxy silhouettes that allude to architectural tropes of the modern, colonial and pre-Columbian eras. The three circle each other awkwardly in time to folksy marimba music until they eventually collide with one another, destroying their costumes to reveal the bare bodies underneath. A playful articulation of Guatemala’s complex history at odds with itself morphs into a reminder of the human toll of violence in the country, which stretches back through the centuries but is most recently defined by its decades-long civil war.

Installation shot of A Decolonial Atlas

Tania Candiani and Paulo Nazareth’s video works are presented together in this section, likely because of their shared interests in cyclical time, repetition, and site-based performance. However, in a curatorial gesture that pervades much of the exhibition, the close juxtaposition of the two videos overvalues visual similarities at the expense of context, dissolving the specific meaning of the individual works. Nazaratte’s personal confrontation of the Afro-Brazilian slave trade, generational trauma, and the melancholic desire to undo the wounding effects of history is, to an extent, lost. In its place is an easy pairing of bodies performing surreal ritual actions in the landscape that appeals to a viewer’s registration of the tropes of the Latin American cultural cliché of magical realism.

The section labelled “Countering Extractivism” is dominated by works that challenge the documentary mode. Collage, montage, and multi-channel installation are utilized here to create open narratives that disrupt the rationalism that historically justified resource extraction in the Americas. Pablo Helguera’s collage series Panamerican Suite renders delirious the scientific texts, models, documentary photographs, and cartographic impulses that defined the Developmentalist discourses of neo-colonialism in Cold War-era Latin America. Ore-Giron is featured here again with a two-channel video, Morococha (2014), which documents the brutal and disorienting effects of industrial globalization. In the work, Ore-Giron juxtaposes the remains of a relocated town in the Peruvian Andes—razed to make way for a Chinese-owned copper mine—with its eerily unwelcoming replacement. Excavation here, as elsewhere in the exhibition, acts a metaphor for the cultural changes industrial exploitation has wrought on the region, and for the process of uncovering painful histories.

Iván Argote, Turistas (Isabel Giving a Contract, and Christopher Pointing Out the South, At Bogota), 2012. C-print. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Perrotin.

The excavation of history also looms large in the final section of the exhibition, “Intervening the Archive.” Political dissent is perhaps most explicitly visible here, in works that directly draw on official histories and their channels of distribution to subvert their meanings or point to the absences within them. Marton Robinson’s Money Talk (2012-15) draws on the tradition of Latin American conceptual projects of dematerialization from the 1970s. Artists like Cildo Meireles hi-jacked modes of everyday circulation, from currency to Coca-Cola bottles, as minor—and untraceable—gestures of political resistance. Here Robinson continues the tradition by inserting black historical figures onto Costa Rican currency, insisting on the underrecognized role of black labor in the country’s formation. The project asks how everyday objects and gestures affirm official histories while masking others.

Paulo Nazareth’s Antropologie Do Negro II (2014), a haunting video performance in which the artist buries himself in human remains retrieved from a former asylum, presents an exorcism of generational trauma related to repressed racial violence. The work is unfortunately watered down by its pairing with Ricardo Estrada’s Cihuacoatl (2009), a photograph of a heavily tattooed male body performing with a human skull. Estrada’s image, while conjuring an interesting comparison of Chicano machismo to Pre-Columbian ritual violence, bears little conceptual or affective resemblance to Nazareth’s deeply felt poetic remembrance. This aesthetic flattening on the part of the curators does a disservice to both works, alienating them from their specific Mexican and Brazilian contexts for the sake of visual affinity. This form of curating through typology does little more than help codify an aesthetics of death within Latin American art, confirming the expectations of what Latin American art can or should do within the global art system.

Two nearby works set a different tone. Iván Argote’s video Barcelona (2014) documents the artist setting fire to a statue in Spain depicting an Indian kneeling before a Padre. Laura Huertas Millán’s video Journey to a Land Otherwise Known (2011) narrates and re-enacts journal entries of European colonial explorers in the artificial confines of a French greenhouse. In these gestures, and in Argote’s doctored photographs of colonial monuments cast as clueless tourists, both artists occupy the oblique cultural position of the trickster, what art critic Jean Fisher described as “the ambiguous figure that makes possible a critical hermeneutics of the social through its very resistance to inflexible and untenable interpretations of reality.”[1] Inflected with humor and a kind of self-aware futility, these works intentionally misapply colonial logics to reveal their absurdity. Interestingly, both are Latin American artists working in Europe, and the ironic detachment of their gestures speaks to a certain level of cultural mobility.

JOURNEY TO A LAND OTHERWISE KNOWN - trailer from Laura Huertas Millán on Vimeo.

When we discuss issues of representation within contemporary art, the term “agency” is often trotted out as an end goal, yet it goes largely undefined. Too frequently it is invoked as a reductive solution to a complex problem, wherein radical liberatory politics are made to sit uneasily within an elite and commodity-driven system like the art world. For Fisher, “agency means understanding the structures of power and the representational languages that sustain them, in which the self is entangled as both a symptom and a mediator.”[2] The challenge then for artists attempting to construct a decolonial atlas is to critically occupy this simultaneous position as “symptom and mediator” of the co-opting cultural machine, standing alongside or within systems of power, but subverting their codes. But what does this subversion look like?

Throughout the exhibition, strategies of performance and embodiment offer the potential for cultural resistance. However, it is worth questioning whether this tendency, which is so overwhelmingly present in an exhibition that covers an enormous geographical region, is a product of curatorial editorializing. What does it mean for the curators to seek out work in which the artists’ body is central? To what extent are artists from the global South, indigenous artists, or artists from other explicitly marginal positions expected to present their identities through their bodies, in order to be rendered legible and even marketable within the global art system? Is this a mediation of the politics of representation in contemporary art, or a symptom of its ability to co-opt revolutionary energies and marginal subjectivities?

Within the international art context and what philosopher Jacques Rancière has described as the “ethical turn” in contemporary aesthetics, bodily representations of marginality become a kind of cultural currency. In the context of Latin American art, this fixation on embodiment echoes a longer history of Latin America’s presentation as the sensual, irrational counterpart to Europe and later the United States, the spirit and body to a higher mind that justified exploitation of its resources and subjugation of its people. This ideological holdover is acknowledged by the curators, who cite explorer, philosopher, and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt’s dualistic formation of the spirit of the Americas as an ideological framework with which the artists on view are still wrestling. What does it mean to continually revisit colonial formulations in order to address contemporary issues of representation? Do they mask, or help us to understand, current realities?

Carlos Motta’s queering of history, specifically of Humboldt’s travels throughout the Americas, addresses these problems, utilizing a narrative strategy present throughout the exhibition that blends what is known within the historical archive with what is absent. Motta draws from Humboldt’s archives, displaying letters to a male soldier and possible lover in order to read them against the gendered language of conquest. Juxtaposed with objects that suggest an archaeology of pre-Columbian same-sex desire, Motta’s project embodies a stranger, more complex codependency than is typically associated with colonial dynamics.

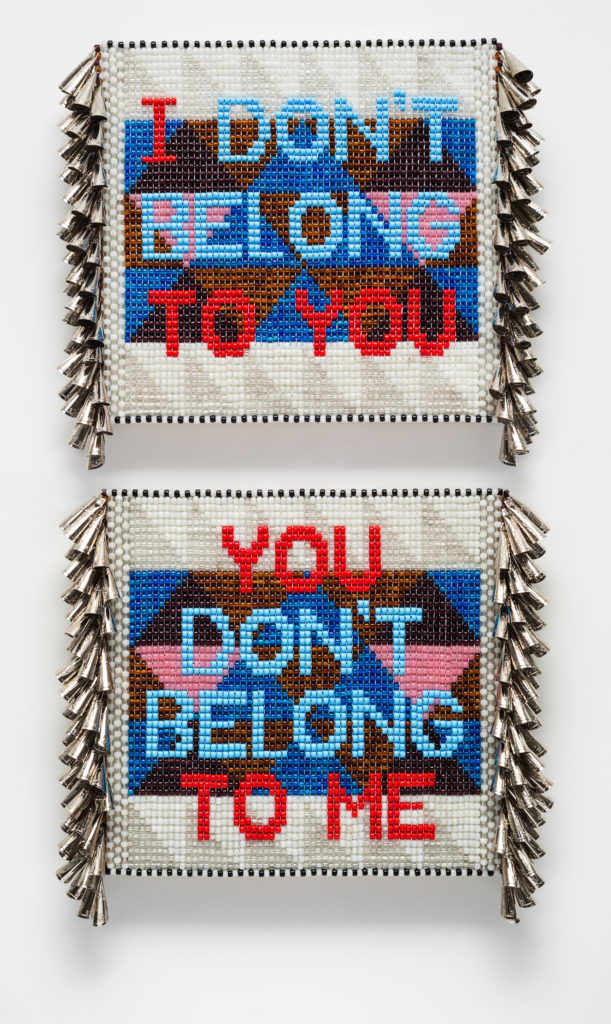

Jeffrey Gibson, I Don't Belong to You, You Don't Belong to Me, 2016. Glass beads, tin jingles, artificial sinew, acrylic felt, canvas, over wood panel. The Alfond Collection of Conteporary Art, Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Rollins College. Image courtesy of the artist and Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles, California.

Similarly, Motta’s video essay Deseos (2015) awakens the textual archive through media, blending fiction and history across temporal and geographic boundaries. By weaving together narratives of same-sex desire and repression from across the globe, queerness becomes a strategy akin to cultural nomadism, a sort of universal difference that allows transgressions against the limits of time, space, and cultural coherence. As Chicana feminist theorist Gloria Anzaldúa wrote, “Being the supreme crossers of cultures, homosexuals have strong bonds with the queer white, Black, Asian, Native American, Latino and with the queer in Italy, Australia and the rest of the planet. We come from all colors, all classes, all races, all time periods. Our role is to link people with each other. . . . it is to transfer ideas and information from one culture to another.”[3] Queer consciousness, she claims, exists inherently in the borderlands between cultures as well as genders, producing spaces teaming with the possibility for coalitional politics.

Many of the embodied strategies on view throughout the exhibition are performed by queer artists, who meld and misuse tradition and contemporaneity to pose important questions about cultural authority and the value of authenticity, transcending problems of the culturally representative artist. Near the entrance to the exhibition, Jeffrey Gibson’s shimmering beaded wall piece reads, “I Don’t Belong to You / You Don’t Belong to Me.” Here, a statement of interpersonal liberation drawn from the queer pop icon George Michael can be readily applied to the broader dilemma of cultural ownership and representation. In the context of this exhibition, it offers space to imagine a new pan-American social landscape, one that transcends the painful lineage of cooptation, enforced dependency, and exploitation in favor of a social project centered on personal and collective emancipation.

[1] Jean Fisher, “Art, Agency, and the Hermetic Imagination,” from Global Cultures: A Visual Anthology, 2011, 38.

[2] Ibid., 37

[3] Gloria Anzaldúa, “Towards a New Consciousness,” from Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 1987, p. 106.

A Decolonial Atlas: Strategies in Contemporary Art of the Americas is on view at the Tufts University Art Gallery through April 15.

1 Comment

Pingback: On the Front Line: T.C. Cannon at the Peabody Essex Museum - Big Red & Shiny