La Tierra del Olvido is the latest exhibition to be featured at Inquilinos Boricuas en Accion’s La Galería. Curated by Julie Gangrand and Juan Obando, the team behind Lucero—a curatorial platform operating in Boston—the show exhibits two Latina artists in honor of Women’s History Month. The selected artists, Rebakak Vargas and Stephanie Aguayo, elaborate on heavily mitigated memory, cultural fixation, and romanticized tragedy.

La Tierra del Olvido, or “The Land of Forgetfulness,” borrows its title from a famous track by musician and actor Carlos Vives. Vibrant and rhythmic, the track combines a multitude of musical traditions both from his native Colombia and foreign sources: rock, merengue, salsa, and pop. At the exhibit’s opening night, Juan Obando described this fusion genre of tropipop as a force that both “creates and negates” culture.[1] While the genre may highlight the varied and beautiful tropical settings of Latin America and the generosity of its inhabitants, it erases the multitudinous struggles of its citizens who struggle with political turmoil, natural disaster, international meddling, revolution, and counter-revolution.

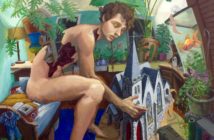

The ways in which we forget beget methods with which to remember, and the recursive cycle of forgetting and remembering take on a life of its own—for better or for worse. The works on view play with how we create memories through objects and media, and the displacing effects these factors have on historical and present-day realities. Vargas contemplates on contexts that are removed from cultural objects, while Aguayo creates skewed contexts from real life media sources.

Rebakak Vargas’ parents were forced to flee their home in Nicaragua due to the revolution and counter-revolution. Her work is a quiet reflection on finding her cultural past through objects and materials in the present. For the exhibit, she produced and printed two booklets, Recámaras vacías and Decoraciones para el Hogar Nicararaguënse.

The first booklet displays Nicaraguan crafts and art objects iconic of her home region on a stark white background. When I spoke to her, she shared that the forced emigration of not only her own parents but many others is marked by enormous emotional duress and the loss of most, if not all, material possessions, which engenders a fear of forgetting history and home Like the contrast between the colorful miniatures and the stark white backgrounds, the value that her parents might derive and the value a tourist might depend on context, which the images intentionally offer little of. Displaying these objects is likewise divergent. In the home of a traveler or tourist, they represent sunny vistas and leisure, a kind of willful forgetfulness of the nation’s embattled history with the United States. In the home of a refugee, they become symbols for loss and memories of distant homes.

An animated collage titled Altares vacíos is projected onto the opposite wall, featuring architectural elements and objects flitting about and dancing on plain white space. As a foreign observer, I could only participate in spectacle, whereas Vargas and others of Nicaraguan descent are able to participate in memory. These fragments, while meaningful in context, become mere novelty from an outside perspective like my own, and I have no other recourse but to wonder. Her third piece, Viajando sin ver, demonstrates this extrapolatory practice. From the vantage point of various vehicles, Nicaragua stretches out before the viewer. Some views are on the highway, some take in the rich natural vistas, and some tape the local citizens. Gathered from Youtube, news sources, and blogs, the video clips reveal what beauty lies in the eye of the beholder. For Youtube especially, user-created content has the disturbing potential to efface news sources with personally biased views of different contexts. The tourists, who frequently commentate as they tape, focus on historical sites, natural landmarks, and marketplaces, embodying a kind of animated postcard that is pleasing to the eye, but not to the social historian. The other clips, sourced from news reports, display the nation’s unhappy realities that would never be mentioned in a tropipop song by Carlos Vives.

Stephanie Aguayo’s Island "Scent"sation transforms a real-life CNN interview with Daddy Yankee, a collaborator on last summer’s ubiquitous “Despacito,” into a polemic on America’s continued lack of intervention in the wake of Hurricane Maria and capitalist interest fueling fantasies of ego-centered charity. The artist fooled even me when she overlaid the Lower Third of the original and replaced it with “Candle maker superstar, Daddy Yankee, speaks on his inspiration for the new scent fans are just dying for” (artist’s emphasis). Daddy Yankee, dour and soulful, pleads for help on behalf of Puerto Rico. The camera pans to blocks featured in the music video, now battered beyond recognition. Below the screen were placed eight candles with Daddy Yankee’s image and the name of the scent, “Island Suffering.” An imploring critique was printed on the labels. “For a small donation of $1 mil [sic]you can feel a sense of self-gratification, and burn the sweet scent of ‘Island Suffering.’” The reference to New England’s Yankee Candle, itself a patriotically titled product, brings to mind our increasingly isolationist political rhetoric, one that extends “Americanness” to select people, bringing harm to those in need—land of forgetfulness indeed.

Stephanie Aguayo’s Island "Scent"sation. Photo courtesy of Julia Cseko.

The tendency to romanticize, and thus keep at spiritual arm’s length, extends into an ambitious installation, SOS (Sensualmente Obtener Salvacion). From two heavy-duty chains, a cobbled-together raft sways. In front of it is an enticing, yet generic ocean view with all the frills: palms, glistening water, and an effulgent sun. Live flowers litter the swing’s surface, laying out the scene for a would-be romance. Three digital screens are placed in the center of the projection, depicting seemingly divergent scenes that coexist with one another, but display startlingly disparate, yet intermingled scenes. The top displays desperate emigrants sailing the open sea on orange rafts from Cuba to the United States. The bottommost screen has idyllic beach views spackled with professional models and promises of memorable nights in paradise—as far removed from reality as one can get. The middle, tellingly, is the iconic scene in “Titanic” where Jack bids his final farewells to Rose and sinks into the icy depths. The romantic melds with the tragic, creating rose-tinted lenses that do worse than erase tragedy, it revels in it, much like the labels on the Daddy Yankee candles.

While Vargas chose to strip away context with the stark white grounds and Aguayo chose to create them with media outlets, both strike at the core of our exceedingly selective memories. External and tourist-driven media run the risk of erasing pressing issues and over-simplifying complex cultures and histories. Many have heard “Despacito” on repeat, but forget that even this week, 11% of Puerto Rico is still without power in the wake of the hurricane.[2] We may support local crafters by purchasing their goods but proceed little beyond the external novelty. Bringing these dynamics to light, Aguayo and Vargas make the audience aware of the filtering veil’s weight and encourage them to lift it from their eyes.

La Tierra del Olvido will be on view at the Villa Victoria Center for the Arts until March 23rd. La Galeria is open Monday through Friday by appointment at 617-927-1717. An artist talk will be hosted at the gallery (85 W. Newton St.) on March 23rd at 6:30 p.m.

[1] Gargando, Julia and Juan Obando (exhibition curators), conversation with exhibition attendees, March 2018, Boston, Massachusetts.

[2] https://www.npr.org/2018/03/07/591681107/6-months-after-hurricanes-11-percent-of-puerto-rico-is-still-without-power