In 1951, the German philosopher Theodor Adorno wrote, “There can be no poetry after Auschwitz.” His assertion is pardonable but profoundly untenable. The supposed hole in the production of German art after 1943 was long understood as “the gap,” by historians to express a general apathy toward the creation of art. According to this narrative, post-war Germany focused on economic recovery and restitution, apathetic to creativity or altogether unable to create. Cultural advancement was low on Germany’s priority list, with a public still averse to modern art as defined by Hitler. While only about a quarter of artists labeled “Degenerate” by the Reich fled the country, they largely comprised the most important of the German Expressionists, others of whom committed suicide or perished in the concentration camps. Some remained in Germany but ceased working, floundering in what the Expressionist Ernest Barlach described as “a state of ‘inner emigration.’”

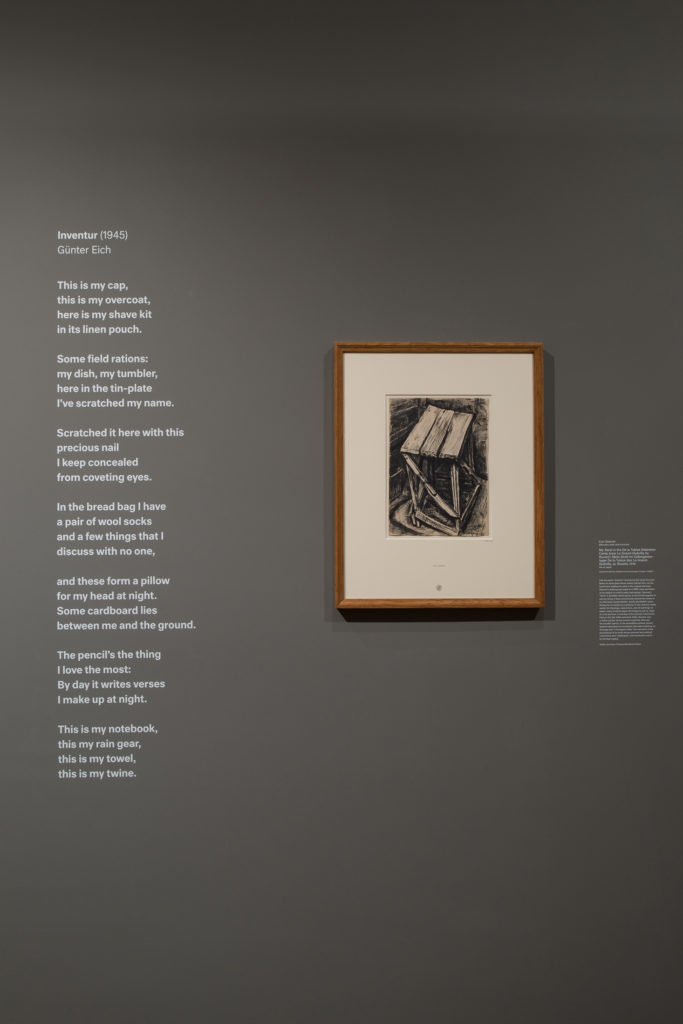

Installation of Inventur. Photo: Karen Philippi; © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Inventur, the German word for “inventory” or “taking stock,” comes from a 1945 poem by the largely apolitical, complacent Günter Eich. Written in a POW camp, the line “Scratched here with this precious nail/I keep concealed/from coveting eyes” vividly conjures images of defiant artists working in privacy during Nazi rule in any available medium. But as curator Lynette Roth demonstrates, the notion of Inventur runs twofold. First is the collective reckoning with guilt and the relief in the wake of the Holocaust. The second is a liberation of style among German artists, where the country’s four newly-established Allied zones made for the impossibility of collective styles or pursuits. German art critic Will Grohmann observed that “There is a lot of confusion… Right now everything is being tried again.” The overwhelming assortment of emerging styles, experimental mediums and philosophies of working artists had exploded into what is known as Postwar Pluralism. The willful abnegation of single mediums and styles gave rise to groups and collectives that worked toward common artistic - if not stylistic - goals, as had their precursors.

Inventur opens with nine ink drawings by Wilhelm Rudolph created in 1945-46 depicting the rubble of Dresden, where he lost his home, studio, and work. Their hasty, loose execution and muscular hatching nevertheless evoke a Piranesi-like precision. It is the most visually narrative series of images, foisting a concrete reminder of both devastation and the trembling anxiety of recovery.

Installation of Inventur. Photo: Karen Philippi; © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Like Rudolph, the artist Juro Kubicek takes a deliberate evaluation - or stock - of recovery after Nazi rule, this time via a sketchbook-cum piss-take of Nazism’s requisite tome Mein Kampf. While the drawings in the pad are reminiscent of Friedrich’s Teutonic Romanticism, it’s title, Mein K(r)ampf (roughly translating as “spasm” but frequently used in reference to stomach pains), is a jab at Hitler’s renowned room-clearing digestive issues. Not restricting himself to one medium even in the context of his journal, he weaves his own written screed of opposition, including bawdy cartoons of prostitutes clamoring over an impassioned Goebbels.

Kubicek looked to New York, the new epicenter of the art world, particularly Abstract Expressionism, as did several of the exhibition’s artists. While their execution is generally jaggedly severe (reminiscent of Expressionist woodcuts or the angularity of German Renaissance drapery folds), the resemblance to mid-career Pollock and de Kooning is unmistakable.

The Ab-Exers, despite their domination of the art world during the 1940s, were not the only Americans to which these diverse groups turned. While Northern artists like Munch and Klee remained influential along with the Western Surrealism of de Chirico and Dali, American influence runs like a choppy river throughout the show. Jeanne Mammen’s 1945 oil Falling Facades (Berlin Ruins) is one of many works that bare an uncanny resemblance in its three-dimensional bump-and-hollow abstraction to the work of Dove or even the concrete, quasi-Cubist/Futurism of Duchamp’s then thirty-plus-year-old Nude Descending a Staircase #2. Others looked closer to home. Harald Duwe’s unnerving Carnival Feast depicts a cellulite-ridden couple gorge-ing themselves with shameless abandon on what appears to be human organs and fire water, resting comfortably with the grotesquery of the artist’s forebearers Dix and Grosz.

Installation of Inventur. Photo: Karen Philippi; © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Several artists expanded upon mediums still heavily tied to Germany, if only by mid-century association. Hann Trier’s series of six color woodcuts, I/I-VI, from 1950 are carved into abstracted shapes and printed in various colors - no more than two at a time. Rearranged to be printed in different configurations, the effect is that of Appel, Jorn, and the Northern COBRA artists.

It’s tempting to turn a slow walk through Inventur into a game of match the artist with their influence, but this would be a grievous mistake on the viewer’s part. To neglect certain wholly unique works created in isolation or made in small collectives would be to reject the notion that art born of trauma, discord, and mass uncertainty can release an atavistic impulsivity spawned seemingly from the ether. K.O. Gotz’s Airpump Studies (1945) evince a thoughtful approach to abstraction via poured watercolor washes that may stand as compositional springboards for larger works but also stand alone in sublime, deceptive simplicity. Indeed, with their mottled, washy centers with spindly lines jutting out like an entomologist’s specimen, they demand the viewer to define simplicity for themselves. Many will walk past these not out of disinterest, but because the diversity of the work in Inventur is so varied that it is almost impossible for visitors to absorb the entire show in one visit.

Installation of Inventur. Photo: Karen Philippi; © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Despite a logical semblance of order on the curator’s part - in the end, there is no “right” way to navigate the show. To return to Adorno, his writings on “mass culture” capture the admixture of discord, isolation, and transmission of ideas that bounce around the exhibit from piece to piece, creating a web that connects them all: “What is important.. is the sense of belonging, …identification, without paying particular attention to [the art’s]content.” In this case, the more attention payed to content, the more we puzzle over the artists’ impetus behind their creation.

Inventur—Art in Germany, 1943–55 is on view through June 3, 2018.