Photographer Nicholas Nixon’s exhibition, Persistence of Vision, centers around one of his most renowned series. The Brown Sisters began with an accidental discovery, not in the way of technique, but by capturing an image that proved worthy of recreating yearly for over forty years.

Nicholas Nixon, The Brown Sisters, New Canaan, Connecticut, 1975. Gelatin silver print, 20 × 24 inches (50.8 × 61 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

Nixon describes making the first Brown Sisters picture in 1975 while feeling “on edge” around his now-wife’s family. He asked his subjects — his wife, Bebe and her three sisters, Heather, Mimi, and Laurie — to pose however they liked. “This day was just really, really, really hot,” Nixon says, but that isn’t how you might imagine it while viewing The Brown Sisters, New Canaan, Connecticut. The sisters’ white linen and cotton clothing is fresh-looking, and their faces do not reflect the light of Nixon’s flash. With their composed expressions, the four subjects look anything but flustered. The photograph is reminiscent of classic family photos but contains none of the polished cheer that the artist disliked within the stiff, “stage-managed” photographs the Brown family organized in the past. This previous ritual may have provided a way for them to document their joy, but Nixon craved more range. This range includes joy, but also uncertainty, tenacity, pride, seriousness, sometimes even subtle frustration or sadness. Some images mark occasions, like The Brown Sisters, Hartford, Connecticut, taken at a graduation, but most are taken for the sake of the project.

Nicholas Nixon, The Brown Sisters, Concord, Massachusetts, 1992. Gelatin silver print, 20 × 24 inches (50.8 × 61 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

The Brown Sisters photographs are endearing. It is easy to feel familiar with the women; each photograph like an exchange. It helps that each of the sisters carries a quiet expressiveness and that their beauty in the first years of the series has been given the same prominence in each successive year. The sense of relationship between the subjects and artist is palpable; the latest photograph of the series, The Brown Sisters, Truro, Massachusetts, seems to impart a sense of shared knowledge. Bebe, who we get to know through all of the solo portraits in the exhibit, stands in the back, the sisters on each side of her with chins tilted upward, as if in acknowledgment of the viewer, but also of their mutual experience. In a previous image of the same name, taken in 2011, two of the sisters look in another direction; in the next, The Brown Sisters, Boston Massachusetts, they rejoin in an embrace. The embraces become more numerous as time goes on.

Nicholas Nixon, View of Essex Street, Near the Massachusetts Turnpike, Boston, 1976. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

In the audio tour, Nixon describes his own attempts to limit his work to the most respectful of material, but his concern is constantly challenged by a sense of urgency to produce unflinching work. These challenging moments appear frequently in Persistence of Vision. The Brown Sisters are accompanied by 8x10 shots of other subject matter done during the same year of each annual photograph of the sisters. These include a myriad of subject matter: architectural, aerial shots; portraits of his family members; people who agreed to work with him for some time, and strangers.

Nicholas Nixon, C.C., Boston, 1983. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

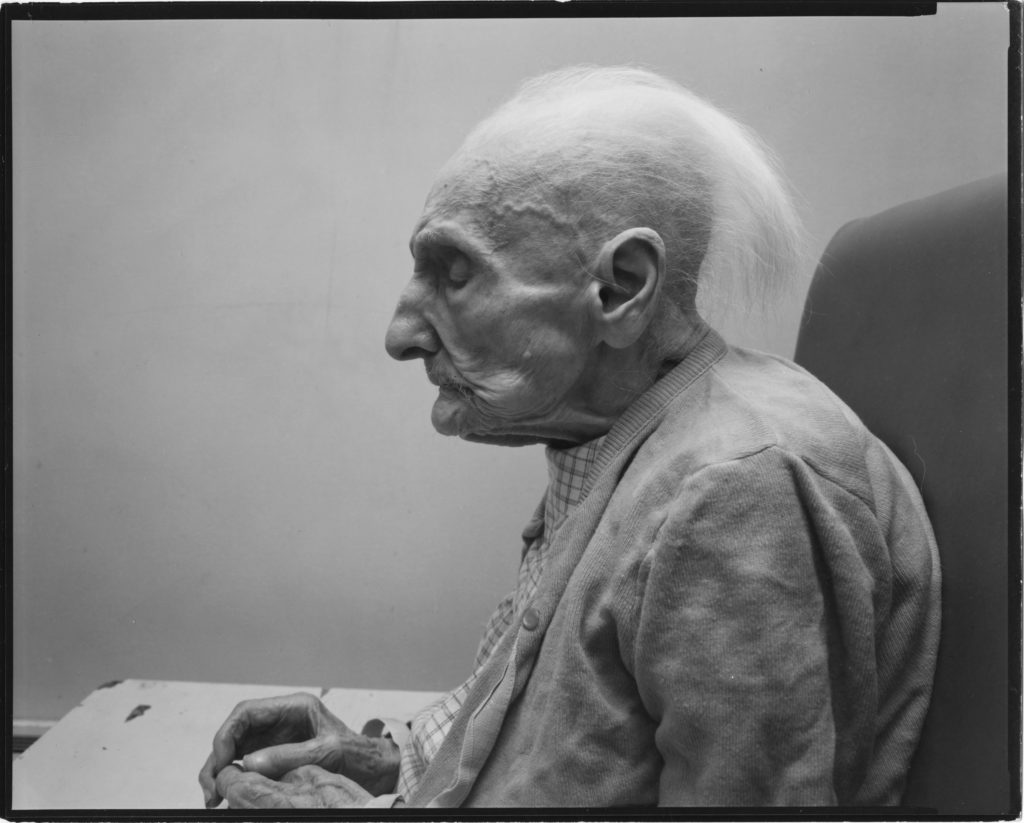

While volunteering at a Boston-area nursing home, Nixon initially promised himself to refrain from photographing the elderly patients he worked with, but in time felt compelled to. Hard to look at, the photographs of the elderly hold nothing back of the truth. They are sad, but these are sad moments. A.E., Boston, which shows a woman with a dejected expression, is possibly the hardest to endure, but also makes every wrinkle in her face appear beautiful. Another photograph featured from the same year, titled Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1985, depicts not aging, but an essential youthfulness. His wife holds his young son, whose skin, with its beautiful and delicate appearance echoes the woman in A.E., Boston, pictured just above.

Nicholas Nixon, Tom Moran, Boston, 1988. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

The photographs of Nixon’s family seem to inform the rest in their sensitivity to aging, to respect, and to closeness. It is daring, though, to try to achieve the same familiar tone in a series like People With Aids, through which he tried to answer his own question, “what if there were a group of pictures that showed individuals?”, pushing back against what he saw as the faceless media portrayal of those with AIDs. Working with those who lived with the disease, he captured both the peaceful moments and more agonizing ones. Catherine and Tom Moran, East Braintree, Massachusetts, 1987, shows Moran embraced by his mother, but in others, the subjects are by themselves. Tom Moran, Boston, Massachusetts, 1988, one of the last images taken of Moran, reminds us that the disease is real and impactful, capable of wearing a person down. Nixon makes it a practice to simply ask subjects to “be present.” Like his images of the Brown Sisters, the power of Nicholas Nixon’s exhibition is seeing the truth revealed over time through a wide range of emotions that should all be seen, acknowledged, and felt.

Persistence of Vision is on view at the ICA until April 22, 2018.

- Nicholas Nixon, Self, Brookline, 2009. Gelatin silver print, 14 × 11 inches (35.6 × 27.9 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

- Nicholas Nixon, John Royston, Easton, Massachusetts, 2006. Gelatin silver print, 10 × 8 inches (25.4 × 20.3 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

- Nicholas Nixon, Sam, St. Maries de la Mar, France, 1997. Gelatin silver print, 10 × 8 inches (25.4 × 20.3 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

- Nicholas Nixon, View of Boston Common, 2002. Gelatin silver print, 20 × 24 inches (50.8 × 61 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

- Nicholas Nixon, Covington, Kentucky, 1982. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon

- Nicholas Nixon, Allentown, Pennsylvania, 1982. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Nicholas Nixon