At the center of Sandra Erbacher’s exhibition is an unsettling discovery found in an unlikely place. While flipping through the book Office Furniture from 1984 on adjustable desks and modular furniture, she found an image of men and women seated around a swastika-shaped desk. Erbacher, who was born and raised in Germany, was so disturbed and intrigued by the image that she did archival research to try to find its original use in product catalogues of the manufacturer, Krueger Wisconsin. Unable to find it or learn the designer’s intentions, the image is a dystopian marriage of workplace productivity linked to the most horrific consequences of bureaucratic efficiency. The powerful image became the inspiration for and centerpiece of Erbacher’s faux corporate lobby now on view at GRIN. The lobby, which Erbacher describes as belonging to a fictional company specializing in “knowledge work,” is not an immersive facsimile. Instead, it relies on the power of suggestion with discrete, individual works that employ universally generic markers of corporate drudgery – the water cooler, photocopier, carpet squares, bland waiting room chairs flanked by indoor plants, and a gold-lettered, aspirational mission statement.

That The World Should Know No Men But These, installation view. Courtesy of GRIN.

Each minimal work here is a product of Erbacher’s historical research into office space and its link to bureaucratic power. Erbacher draws from sources as varied as Herman Miller office furniture catalogues, to George Orwell’s 1984, to the writings of social theorist Max Weber, who thought professional specialization turned workers into alienated cogs and wrote the phrase borrowed for the exhibition’s title, That the World Should Know No Men but These. Erbacher’s touch is generally light, often relying on putting appropriated images, diagrams, and text together to form slightly altered combinations. The stock photo of people at the swastika-shaped desk is enlarged and hung against squares of yellow and brown carpet tiles to become ComSystem (2017). Her chairs are perfectly nondescript and like functional readymades meant for sitting like an exhibition bench. If this is the knowledge economy, it is not the flashy lobby of a tech startup, and it is more indicative of Erbacher’s interest in where we have been as she studies the history of office design, its relationship to corporate aspirations, and its actual impact on worker liberation (or lack thereof). This is summed up in one of the found diagrams push-pinned to the wall of an office layout with lines showing what I presume are possibilities for worker interaction, which Erbacher succinctly captions “Circulation of Optimism vs. Established Patterns of Control.”

Sandra Erbacher, ComSystem, 2017.

Archival Inkjet print mounted on di-bond, carpet squares. Courtesy of GRIN.

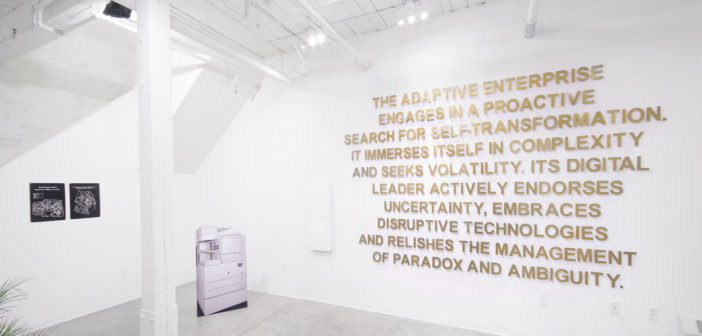

Text is also a major component of a large wall piece that sits opposite the waiting room chairs. The Adaptive Enterprise is a jargon-filled sentence that Erbacher found and lasercut out of acrylic, gold lettering. It proclaims that the “adaptive” company seeks out volatility, complexity, uncertainty, disruptive technologies, and “relishes the management of paradox and ambiguity.” This is the exact opposite of the tenants of bureaucratic predictability and seamless scalability that allow McDonald’s to give you the same burger no matter where you are in the world or Amazon to deliver your package in two days. It is a new ethos written in authoritative, passé lettering, and the gesture is indicative of Erbacher’s skepticism toward our assumption of the progressive trajectory of workplace evolution. Today’s trend of having an open-plan office does not necessarily solve any of the problems of workplace noise and lack of privacy that the notorious cubicle was invented in the 1960s to potentially alleviate. In an interview with Amanda Schmitt, Erbacher expands on these ideas and explains how she does not buy into the idea that individual empowerment will follow as the contemporary office space changes with the increase in freelance workers.

Sandra Erbacher, Utopian Structure for the Cultivation of Social Connectivity, 2017.

Styrofoam, plaster, wood, laminate. Courtesy of GRIN.

A cynical and humorous view of this historical march “forward” is further expressed by Erbacher’s riff on the ubiquitous office lobby sculpture. Carved out of Styrofoam and coated in hydrocal, ghostly white water bottles form a stacked tower resting on a cheesy, faux-granite laminate plinth. A formal nod to Brancusi’s Endless Column, the lofty and ridiculous title - The Utopian Structure for the Cultivation of Social Connectivity – makes fun of modernist ambitions to change social life through aesthetics and the failure of many such designs to erase workplace anomie. Aside from the carving of these water bottles where we can see Erbacher’s hand and the stains on the waiting room chairs, there is no sign of much life in this office lobby. A reproduction of an image of a photocopier mounted to a gatorboard placard risks being a little gimmicky, but makes clear that Erbacher is most interested in our idea of the perfect office and the aspirational language used to market it. In the found photograph that prompted her investigation of workers huddled around a totalitarian symbol, grand ambitions for employee agency are laid bare as just another mechanism for social control, and like Erbacher’s office lobby, left feeling empty.

That The World Should Know No Men But These is on view at GRIN through November 11.