For over two years Mario Garcia Torres obsessively researched the circumstances surrounding an obscure assignment given to a small group of students at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) in 1969. In a process he has likened to detective work, the young Mexico-born artist fastidiously mined archives, tracked down participating students, conducted interviews, and even journeyed to Halifax to document a class reunion.1 Telexed to Halifax by New York-based conceptual artist Robert Barry, the assignment consisted of a simple proposal. It neither launched the career of a new art star, nor begot transformative artistic products. In fact, it produced no physical trace at all:

"The students will gather together in a group and decide on a single common idea. The idea can be of any nature, simple or complex. This idea will be known only to the members of the group. You or I will not know it. The piece will remain in existence as long as the idea remains in the confines of the group. If just one student unknown to anyone else at any time, informs someone outside the group the piece will cease to exist. It may exist for a few seconds or it may go on indefinitely, depending on the human nature of the participating students. We may never know when or if the piece comes to an end."

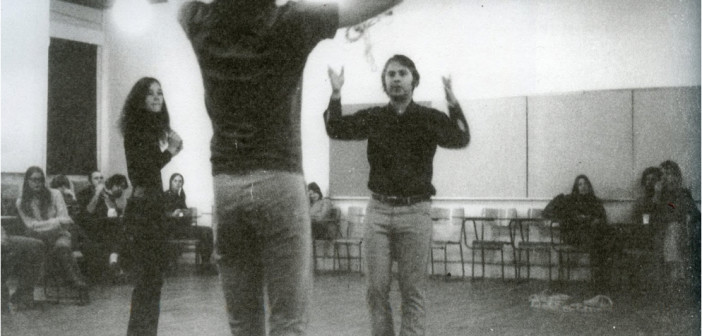

Garcia Torres illustrates his investigation of this assignment in a sparse slideshow entitled What Happens in Halifax Stays in Halifax (in 36 Slides), 2004-2006. The 36 slightly fuzzy black and white slides projected against a white wall quietly detail his quest for truths about this mysterious, singular assignment. Despite its microscopic focus, What Happens in Halifax Stays in Halifax has had international appeal—its exhibition history includes the 2007 Venice Biennale and the 2010 Taipei Biennale.

Garcia Torres is not alone in his interest in excavating the proposal-based assignments that began to infiltrate art curricula in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 2008, Brooklyn-based artist Eric Doeringer recreated John Baldessari’s I will not make any more boring art, an instruction piece which students carried out for a 1971 exhibition of the artist’s work at NSCAD’s Mezzanine Gallery. Baldessari’s practice was also the subject of a 2012 exhibition at CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art. "John Baldessari: Class Assignments, (Optional)" asked current CCA students to carry out the instruction notes from Baldessari’s Post-Studio class at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). "The Experimental Impulse," a 2011 exhibition held at REDCAT as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time initiative, looked more broadly at CalArts formative years. These are just a few examples of the proliferation of contemporary projects and exhibitions based on dematerialized assignments and defunct classes from over forty years ago.

Mario García Torres

Mario García TorresWhat Happens in Halifax Stays in Halifax (In 36 Slides)

2004-2006

Image courtesy of EgoDesign.CA.

This resurgence of interest could be attributed to what art historian Claire Bishop has described as the "retrospectivity" of contemporary art: the current fetish for cultural artifacts or archival materials.2 Or it could be categorized as part of the "pedagogical turn," the term given to describe the recent profusion of artists facilitating educational activities as part of their artistic practice. However, I think this particular trend reflects something more specific: the contrast between the open experimentalism of the proposal-based assignments used at schools like CalArts and NSCAD and the hyper-professionalization of art schools today.

CalArts and NSCAD represented the foremost testing grounds of the radical new pedagogical approach that emerged at premier North American art schools in the late-1960s. This approach privileged idea-based experimentation over the production of art objects and fostered an ethos of collective exploration and creative risk-taking. If we follow Garcia Torres’s lead and look more deeply at one of the most radical examples of this approach, David Askevold’s 1969-1972 Projects Class at NSCAD, we glimpse an open learning environment that has almost no trace in the competitive, professionalized sphere of art schools today.

The Projects Class represented the beginnings of a new era at NSCAD. (The school had previously existed as a non-degree granting provincial art school with a focus on landscape painting.) After the artistic and socio-political ruptures of the 1960s, the administration realized that only a curriculum overhaul could save the school from complete obsolescence. They reacted by appointing a new president: Garry Neill Kennedy, a 32-year old Nova Scotia native who had been making moves as head of the art department at Northland College in Wisconsin. Kennedy sought to make the school "relevant" by taking the contemporary art world as his pedagogical model. Rather than rehashing any existing art education methodologies, Kennedy turned to the budding conceptual art movement as his principal paragon. Mirroring the strategy and language of conceptual art, Kennedy has said of his approach: "The ideas would come first and the structures would follow."3 He created several initiatives for fostering interactions with young innovative artists and appointed instructors who would do the same. The restructuring at NSCAD included leaving permanent faculty positions open so that salaries could be divided up among several visiting artists, establishing a printing press that published emerging artists’ works, and directly connecting students to broader networks of artists through information networks like mail art and alternative periodicals.4

Kennedy hired David Askevold, a young, conceptually-oriented video and photo-text artist, to teach a Foundations course in 1968. Wanting to move beyond the skill-acquisition formula of the Foundations model, Askevold evolved the course into what he called the "Projects Class." The class was structured around open-ended instructions, or "Project Proposals," which Askevold solicited from a roster of emerging artists. These proposals translated an emergent conceptual art strategy—propositional instructions—into an educational methodology.5 Participating artists —including Lucy Lippard, Dan Graham, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, and Robert Smithson —were asked to mail, telex, or telephone the class with their proposals. This mail art-inspired structure allowed ideas to flow directly between the participating artists to the students, rather than being mediated through lectures and formalized assignments. Students could choose whether or not to manifest the projects and frequently worked on them collaboratively. Rejecting the role of instructor, Askevold positioned himself as a "moderator" and often joined his students in executing the proposals.6 The idea-based proposals emphasized exploration of creative processes over the production of physical art objects. Through this class structure, Askevold effectively replaced the linear training in artistic skills typical of foundations classes with de-hierarchized open-ended activities.

In the Fall of 1969, Dutch artist Jan Dibbets, mailed the following instructions to the class:

"Photos of tree shadows every 10 minutes.

1. Find a place in a not too closely overgrown part of the woods where there are very clear shadows.

2. Use one or more days to find out exactly how the shadows are moving: when they start and what moment they come into camera view. Try to get as much as you can from the trees in the photos, keeping in mind that their shadows are the most important part of the photos.

3. When everything is ready start taking the photos. #1 — no shadow, #2 — first shadow, #3 — extended shadow, etc. Take one every ten minutes. Choose a day with uninterrupted sunshine.

4. Make a work drawing on paper. Glue all the photos (contact prints — small) in order of succession and hang in order; the negatives on negative-leafs.

5. Make two prints of each on paper 24×24 centimeters and 30×30 centimeters. Hang them in a row, so only the shadow is moving."

The practice of recording the shift in light over the course of a day mirrors Dibbets’ own work at the time, which frequently used serial photographs to document subtle environmental changes. Rather than training students in a specific skill, this project encouraged them to share in the artists’ investigation. It also pushed students out of the studio, asking them to closely observe natural phenomenon. Unlike the traditional landscape painters who previously dominated the school’s faculty, Dibbets’ proposal emphasized the durational process of observation, not a fixed or finished product.

Despite its fresh approach to an observational assignment, Dibbets’ proposal remains somewhat conventional in its specification of medium and its carefully delineated instructions. Sol LeWitt’s project, submitted to the class in the same semester, rejects such preconceived outcomes:

"1. A work that uses the idea of error.

2. A work that uses the idea of incompleteness.

3. A work that uses the idea of infinity.

4. A work that uses the idea of completeness.

5. A work that uses the idea of stupidness.

6. A work that is subversive.

7. A work that is not original.

These could be done in any form chosen by the student. Please ask your students not to do more than two of the above works."

These seven open-ended instructions resemble the tone and form of LeWitt’s "Sentences on Conceptual Art," which the artist published in the art journal 0-9 in 1969. In "Sentences," LeWitt lists guidelines for idea-based art, such as "#10. Ideas can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical."7 As is declared in "Sentences," LeWitt’s Projects Class proposal does not presuppose a fixed result, but instead requires students to generate their own ideas. The proposal also leaves the medium, form, and subject completely open to the students. Several of the guidelines—error, incompleteness, infinity, stupidness, unoriginality—encourage students to question the limits of what constitutes a work of art. This openness links to another "Sentence[] on Conceptual Art:" "#1. Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach."8 In contrast to the objective, mechanistic way that conceptual art is often read, LeWitt endorses the idea that artists possess a special subjective, illogical, even magical level of creativity. In creating guidelines that are free from any preconceived outcome, he encouraged participants to tap into that experimental potential.

Robert Barry

Robert BarryA Work Submitted to the Projects Class, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Fall 1969

Image courtesy of Garry Neill Kennedy

Robert Barry’s proposal, which so captivated Garcia Torres, is similarly open-ended. Beginning in 1967, Barry abandoned painting for dematerialized media such as inert gasses, language, and systems for transmitting information. His interest in non-visual information exchange is evident in his instructions for the projects class, which asks the students to decide upon a "shared idea" that would be kept secret from both Askevold and Barry.

This proposal forecloses the production of anything material, requiring students to work completely conceptually and focus solely on intellectual decision-making processes. It is also contingent upon collaboration between students. Barry’s emphasis on collectivity was in line with Askevold’s pedagogy. As "moderator," the latter encouraged his students to test out ideas together. This enthusiasm for collaboration represents a complete departure from the emphasis on competitive individualism that runs through modern academic art education. The push towards collectivity and exchange instead recalls the radical pedagogy of the Black Mountain College, a major precedent for both NSCAD and CalArts, and John Dewey’s influential theory of experience-based learning.9 However, Askevold was notably drawing not on these precedents, but on contemporary conceptual practice's emphasis on sharing ideas and information.

The open-ended format, as seen in the aforementioned examples, represented tremendous potential for what Italian theorist Umberto Eco describes as "improvised creation" in his influential 1963 essay, "The Poetics of the Open Work." For Eco, open works are those that depend on the participation of the audience for completion. In doing so, they blur the boundaries between the artist and audience, or in the case of the Projects Class, artist and art students, creating new communicative situations and fresh modes of perception.10 By bringing this strategy into the classroom, Askevold not only rejected the traditional art class structure, but also encouraged students to wildly expand their perceptual and aesthetic experiences. By realizing these open proposals in a context completely untainted by the art market, the students that participated in the Projects Class were essentially realizing conceptual art's most utopian potential.11

This ideal of open experimentation has become legendary in the years since the proposals were first enacted. Of the Projects Class, Garcia Torres has said "this program created in the school an open space where conceptual practices could flourish... I think it was definitely a very interesting way of thinking about a school, more as a platform for things to happen."12 The organic freedom of this pedagogical model is clearly very seductive for young artists and curators. What Happens in Halifax Stays in Halifax is tinged with romantic yearning. The work’s nostalgia is evidenced in Garcia Torres’s use of the outmoded display technology of the slide projector and in the slightly out-of-focus black and white images that it projects. As if in homage, the slideshow maintains the orthodox visual and verbal language used by Barry and his conceptual art peers. The number of slides corresponds to the number of takes on a roll of film—a conceit frequently used by photo-conceptualists to eliminate subjective choice. Each slide consists of an objective, documentary snapshot coupled with a simple statement. A slide with a photograph of the Halifax harbor reads: "As usual, that winter morning David Askevold handed out the new instruction piece to be executed." Another, an image of reuniting students, states: "For them the piece was less about dematerialization of the art work than about friendship and loyalty." Some of the text in What Happens in Halifax Stays in Halifax also alludes to the slipperiness of historicizing an immaterial project. One slide suggests that some of the participants no longer remember the original idea. Another reveals that Askevold is rumored to have secretly bugged the students’ meeting, essentially breaking the rules, and therefore the existence of the work, at its very inception. These admissions fuel the mythology that surrounds the proposal, ensuring the continuing legacy of the experiment in information exchange.

Notably, Garcia Torres was first seduced by this myth while enrolled as an MFA student at CalArts (he received his degree in 2005) The Projects Class would have seemed very radical in comparison with to CalArts in the mid-2000s, where a harsh, competitive environment hads supplanted the atmosphere of creative exploration. Here, in what art historian Howard Singerman has described as the "flattened landscape" of contemporary art schools, the crit has has replaced experimental proposals as the core of the curriculum. The discourse is controlled and edited by a small clique of students and faculty.13 Thierry de Duve has labeled this the "attitude-practice-deconstruction" model of education, indicating that it is a system based on critique, rather than production or ideation.11 In the "attitude-practice-deconstruction" system, the innovations of the 1960s and 1970s have been codified and turned into administrative procedures that foreclose, rather than follow, the experimentation of the earlier period.15 Garry Neill Kennedy, who remained president at NSCAD until 1990, has lamented this process, identifying the increasing prioritization of the administration—the ossification of schools’ "institutional skeleton[s]"—as a principle cause.16 This increasing administrative presence and the aggressive competition among art schools to lure students with state of the art facilities and big-name teachers has led to skyrocketing tuition costs. Plus, the multiplication of MFA programs have flooded the art world with "professional artists" who, once graduated, must compete for a tiny pool of residencies, shows, and teaching jobs. This landscape, again, represents a dystopic reversal of the freedom and openness of the art scene in the late-1960s and early-1970s, when artists worked hard to escape the market, rather than enter it.

Today, the legacy of the Project Class seems to exist largely outside of institutionalized academic settings. Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher’s Learning To Love You More, 2002-2009, for example, translated the class’s proposal-based model into an online platform. The Bruce High Quality Foundation, a New York based art collective currently runs a "University," which asks artists to propose public workshops. Meanwhile, art schools—especially those that have introduced the visual art PhD—are more professionalized than ever.

Faced with this ever-increasing professionalization and bureaucratization of art education, teachers and administrators might do well to look to the loose administrative structures and open-ended proposals of the late-1960s and early-1970s as models. Perhaps a rejuvenated embrace of experimentation and openness could guide the formation of a radical new art pedagogy.

- Terrel Seltzer, Rope Trick, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1970 Image courtesy of Garry Neill Kennedy

- Robert Barry A Work Submitted to the Projects Class, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Fall 1969 Image courtesy of Garry Neill Kennedy

- Mario García Torres What Happens in Halifax Stays in Halifax (In 36 Slides) 2004-2006 Image courtesy of EgoDesign.CA.

[1] Mario Garcia Torres in interview with John Menick. Published in John Menick, "What Happened in Halifax: An Interview with Mario Garcia Torres," September 26, 2007. http://www.johnmenick.com/2007/09/mario-garcia-torres-interview

[2] Claire Bishop, "How did we get so nostalgic for modernism?" 14 Sept 2013, Still Searching, FotoMuseum Winterthur, http://blog.fotomuseum.ch/2013/09/1-how-did-we-get-so-nostalgic-for-modernism/

[3] Garry Neill Kennedy, in Bruce Barber, ed., Conceptual Art: The NSCAD Connection 1967-1973 (Halifax, Nova Scotia: NSCAD, 2001), 20.

[4] As a result of these changes, NSCAD became somewhat of an artistic hub. The huge roster of visiting artists were able to experiment with performance, video, lithography, experimental lectures, etc., while on campus. Students were not only able to access these artists, but also join in their projects— they learned technologies.

[5] To give a few examples of this strategy: As early as 1960 Yoko Ono was began creating instruction pieces while involved in the Fluxus movement in the early 1960s. Sol In 1968, LeWitt’s wall drawings began creating wall drawings, which existed primarily as instructions that were could then be carried out by "draftsmen." Artist and Curator Lucy Lippard also used an instruction-based format her well-known "numbers shows."

[6] David Askevold, "The Projects Class: History", in 13. Garry Neil Kennedy, The Last Art College: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968-78. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 13..

[7] Sol LeWitt, "Sentences on Conceptual Art," 1969.

[8] Ibid.

[9] For an outline of Dewey’s theory see: John Dewey, Experience and Education. New York: Collier Books, 1938.

[10] Umberto Eco, The Open Work, translated by Anna Cancogni (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989).

[11] Within the secluded, padded environment of the school, students, teachers, and visiting artists seem to have achieved the ideal evoked by Lucy Lippard in the introduction to 955,000: "Art intended as pure experience doesn't exist until someone experiences it, defying ownership, reproduction, sameness." See: Lucy Lippard, "Introduction," in 955,000 (Vancouver: The Vancouver Art Gallery, January 13-February 8, 1970), n.p.

[12] http://www.johnmenick.com/2007/09/mario-garcia-torres-interview

[13] Howard Singerman, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press: 1999), 211.

[14] Thierry de Duve, "When Form Has Become Attitude — And Beyond." In The Artist and the Academy: Issues in Fine Art Education and The Wider Cultural Context, edited by Stephen Foster and Nicholas deVille, 23-40. (Southampton, UK: John Hansard Gallery, 1994.)

[15] Singerman and DeDuve actually claim that the current system emanates from the c.1970 pedagogical shifts, however, I think that, in their zeal to theorize the trajectory of art education, their analyses overlook actual historical detail of the experimental structure and reception of proposal-based assignments.

[16] Garry Neill Kennedy, "Introduction," in Garry Neill Kennedy, The Last Art College: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968-78 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012).