“Pain is real when you get other people to believe in it. If no one believes in it but you, your pain is madness or hysteria.” – Naomi Wolf

For an exhibition centered on information, I certainly didn’t feel informed after leaving Walid Raad at the ICA. I felt disorientated; like I had just walked out of a top-level security briefing, overwhelmed by the layers of information presented to me and at me. At the same time, I felt like I had just rummaged through the museum’s storage, learning the detailed and occasionally mundane history of its archives. And even still, reflecting on the exhibition’s audio guide (arguably the backbone of the experience), I thought, “Did I just listen to a stand-up show too?”

It is, in fact, this playfully schizophrenic viewing experience, the upending of the “fact” of photography and human perception, and the gap between the authority of the archive and the responsibility of the public to question that authority, in which Walid Raad confidently situates his work. Raad was born in Lebanon in 1967 but emigrated to the United States in 1983 because of the escalating violence of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990). He studied photography at the Rochester Institute of Art and got his PhD at the University of Rochester. He currently teaches at Cooper Union. But even as I’m relaying this obligatory background information, I find myself resisting. And I think that’s because Raad’s biography, as well as the details of the Lebanese Civil War, are only useful tools for experiencing the exhibition up to a point–a point that comes shockingly and disarmingly soon after entering the galleries. After marinating in the exhibition for a few moments, it’s clear that this wielding of “required” knowledge to the viewer and almost immediately relinquishing it from them is very much by design.

Walid Raad, Section 88: Views from outer to inner compartments_ACT XXXI, 2015. Installation view, Walid Raad, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 2016. Photo by John Kennard. © 2016 Walid Raad.

The two bodies of work on view, The Atlas Group (1989-2004) and Scratching on things I could disavow (2007 -), are informed by the events and documentation of the Lebanese Civil War. However, Eva Respini, the Barbara Lee Chief Curator at the ICA, admits in her MoMA catalogue essay, “In both cases, parsing fact from fiction is beside the point.”[i] According to her, both “tell a complex composite truth stretching beyond historical fact, and both rely on storytelling and performance to activate imaginary narratives.”[ii] Interestingly, these imaginary narratives are fully activated by Raad himself as he performs Walkthrough for visitors, assuming the role of a tour guide. A similar experience is available on the audio guide for visitors who are not able to attend the limited number of scheduled performances.

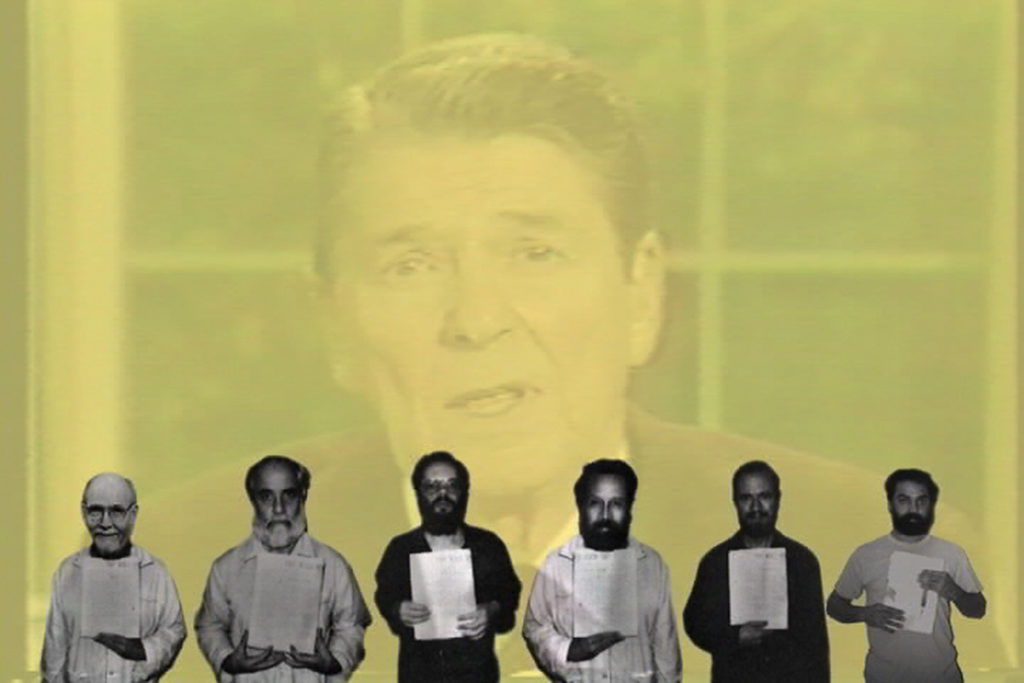

Walid Raad, Hostage: The Bachar tapes (English version), 2001. Video (color, sound), 16:17 minutes. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Jerome Foundation in honor of its founder, Jerome Hill, 2003. © 2016 Walid Raad.

On the audio guide, Raad tells us that there are different kinds of facts: historical, emotional and aesthetic. For him, “an artwork is an interesting instance in which one may be able to maintain all these facts in their continuum and complexity.” It sounds like a radical claim, but Raad backs it up throughout the narration. Whether someone hears Raad in person or via his recording, this performance is the crux of the exhibition; it is the axis through which the viewers circumvent the physical space of the galleries and the porous space between what they’re told and what’s in front of them. Considering the fervor with which he narrates, it sounds like performing is also where Raad himself feels the most engaged. He tells enthralling and detailed stories of recovering art from the rubble of buildings in Beirut, the meticulous archiving of various car engines that litter the streets after car bombings, and outlines the Rube Goldberg-esque architecture of the international art market. After hearing Raad explain these foreign scenarios with such energy and supposed scholarship, one is induced into a stupor; hypnotized by the confidence of his storytelling. The result is an intoxicating sense of bewilderment that is, quite frankly, really entertaining.

But the spectacle comes with a cost, enticing visitors to suspend their disbelief and surrender their own methods of critical judgment much like an audience would in front of a convincing magician. Raad holds several positions at once: artist, narrator, conspiracy theorist, and ringleader–each with nuanced, overlapping sensibilities. Unlike a magic show, however, the audience of Walid Raad becomes privy to the smoke and mirrors. The viewer snapping in and out of a Raad-induced trance might, in fact, be the most palpable experience of the entire show. For me, that happened in two moments: once in The Atlas Group, and again in Scratching . . .

The Atlas Group section is staged in a clean white-cube gallery. The wall text accompanying the work is written in a language that, at first glance, is equally as legible as it is systematic. Very quickly, however, it bombards the viewer with a flurry of “facts,” including that The Atlas Group was founded in 1989 with the mission to research and document the history of Lebanon through the collection and archiving of notebooks, photographs, films, and objects. Even more interesting, and later hilarious, is that I forced myself to reread the seemingly endless barrage of information because I thought that it was required to experience the art. That thought was born out of insecurity: I don’t know anything about the history of Lebanon or the art that is created there. I’m actually not that schooled on photography either. Rather quickly I assumed that I was not the audience for this work, and therefore clung to supplemental forms of information like the wall text and the audio guide.

It turns out, however, I and many Americans are exactly the target audience for this work not only because of our ignorance of the history of the Middle East but more importantly because of our innate need as humans to cling to “the truth.” This need became more evident as I stood in front of Secrets in the open sea (1994/2004) a series of five prints that are various shades of blue. At first, they resemble “post-painterly abstraction” or the cool composition of Minimalism. They might even recall the Mediterranean Sea, or elicit some connotations of the color blue like tranquility, wisdom, or trust. But after “educating” myself by reading the wall text, I discovered that these monochromes apparently had been found buried underneath the rubble of a commercial district in Beirut that was demolished in 1993. The Atlas Group sent several of the prints to laboratories for analysis and were surprised to find that each one has a black-and-white image that was previously invisible. These latent images are of various groups of people who, evidently, had all drowned or were found dead in the Mediterranean between 1975 and 1991.

As soon as I read the last line, I thought to myself, “There’s no way that’s true.” The story was too elaborate. And the prints were in too good of a condition to be found underneath a demolition site. It turns out a lot is hiding in plain sight. According to the MoMA exhibition catalogue of the show, the figures in the latent images never died in the Mediterranean as claimed in the wall text. They were originally photographs from newspapers that documented group gatherings like board meetings.[iii] In fact, The Atlas Group doesn’t exist. After circling back to the introductory wall text, I remembered that the first sentence introduces the group as fictional–a detail that I had casually forgotten. Raad is its only member and none of the artworks on view were collected by the group. They were all appropriated either from original sources (like the newspaper photographs for Secrets . . .) or from Raad’s own photography.

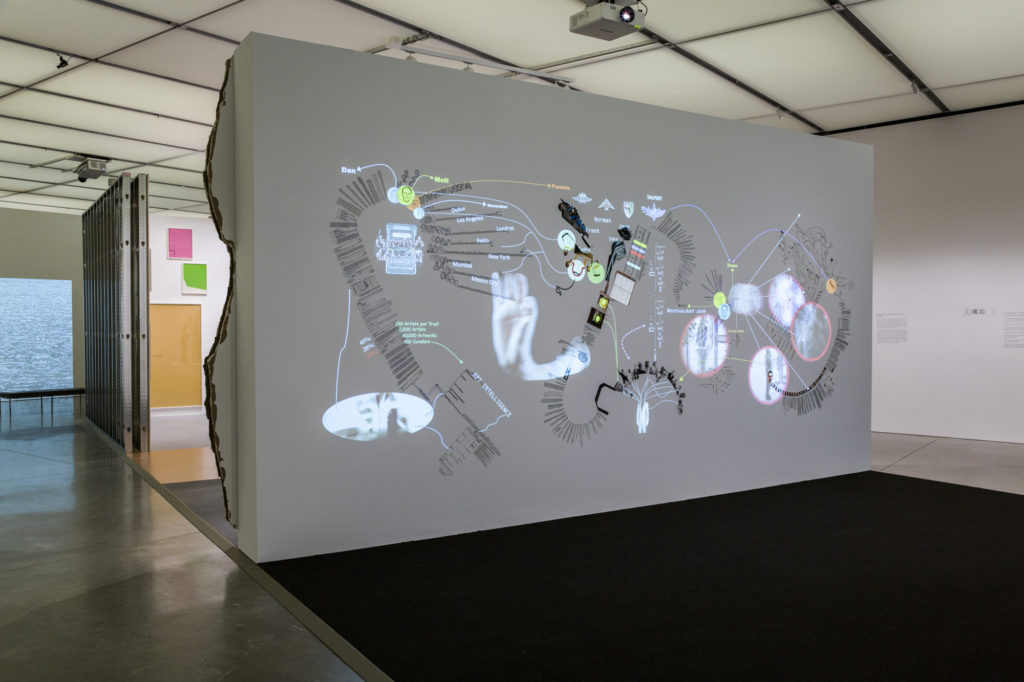

With careful shaping from the audio guide and the wall texts, these documents mutate into what Raad calls “hysterical documents” that are not based on singular facts and memories, but rather “fantasies erected from the material of collective memories.”[iv] Scratching . . . focuses less on the authority of the archive, however, and more on the authority of museums themselves. This section of the exhibition dissects both the intellectual and physical space of the museum by revealing the structures that comprise it. The walls, for example, are not seamless like those in Atlas Group but appear to have been haphazardly ripped out of the side of another building, erected in diagonal procession across the gallery like dominoes about to fall. On the audio guide, Raad explains the design of the international art market by discussing (ranting about) the Artist Pension Trust (APT) that has profoundly complicated ties to the Israeli military. To many viewers, this attempt at transparency is probably very much welcome given the general opacity of the international art market.

Installation view, Walid Raad, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 2016. Photo by John Kennard. © 2016 Walid Raad.

As explicit as Scratching . . . appears to be, I couldn’t help but be reluctant to fall for yet another mirage. Then I encountered Section 139: The Atlas Group (1989-2004), a gallery model from 2008. Here Raad tells arguably his most fantastic story, which I listened to with equal parts suspicion and intrigue. After several years of back and forth with a curator, Raad finally agrees to show The Atlas Group work at a new gallery in Beirut and quickly ships the gallery the work. A few weeks later he visits the gallery in person and sees Section 139. He’s shocked to discover that each of his works has been reduced to 1/100th of its size. Panicked, Raad asks members of the gallery for help. They assure him that this is what they received. Raad comes to the conclusion that his work shrunk after arriving in Lebanon.

Section 139 might be the richest of Raad’s “hysterical documents” because it asserts a profoundly interesting proposition: violence can cause form and objects themselves to change. The story behind Section 139 claims that Raad’s work was actually traumatized from being in Lebanon. This narrative brings up absurd and fascinating questions: could the work return to its normal scale if Raad took it outside of Lebanon? Could it truly be itself ever again? Is one’s artwork diminished by the very nature of being in its creator’s homeland?

Walid Raad, Section 139: The Atlas Group (1989-2004), 2008. Installation view, Walid Raad, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 2016. Photo by John Kennard. © 2016 Walid Raad.

Section 139 resembles a typical gallery model used for exhibition planning, although Raad insists that it isn’t. Here, Raad and Respini present the exhibition as what all exhibitions are: constructions. Standing over Section 139 in the somewhat cramped, dimly-lit gallery feels a lot like movie impressions of a four-star general standing over a miniature version of the battlefield, altering the position of small tanks while carefully considering the possible outcomes. In fact, a curator must have a similar relationship to the gallery model. It’s a place of strategy and control, of preemptively executing ideas “in a vacuum” to see if alternative routes reveal themselves. Yet somehow I didn’t feel more liberated or in control after being granted this transparency. On the contrary, I felt even more insecure and less informed than before. But I’m sure that’s part of the point.

Never have I experienced an exhibition that gave me so much information but made me feel so laughably helpless. The wall text, a common museum tool for educating the viewer, frequently distracts the viewer with fabrications. Visitors might find temporary comfort in the audio guide, but the narration is also the carrot that leads the ass aimlessly around the block. In Walid Raad, it seems like Respini and Raad are a highly effective duo. Her over a decade-long tenure as a curator in the MoMA’s Department of Photography gave her an extensive knowledge of photography’s “slippery” nature in terms of truth telling, which gels perfectly with Raad’s oeuvre. Walid Raad oscillates between being startlingly dense and effortlessly straightforward, producing an entertaining and informative experience that reveals just what can happen when you walk into a room and expect someone else to tell you the “real” story.

[i] Eva Respini, “Slippery Delays and Optical Mysteries: The Work of Walid Raad,” Walid Raad, catalogue preview (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2015), 29, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/publication_pdf/3227/MoMA_WalidRaad_PREVIEW.pdf.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid, 39.

[iv] Ibid, 33.