Up at the Danforth Museum\School through May 15, Volcanoes, Riots, Wrecks, and Nudes is a brilliant exhibition that showcases paintings and prints spanning Edward Hagedorn’s brief career. The title was taken from a 1944 quote wherein Hagedorn listed his favorite subjects. Hagedorn’s Expressionism feels familiar in the best way, born of the same esprit de corps that drove his German contemporaries, living in the shadow of two world wars, to create rough, emotive, graphic work. The exhibition’s curators, Stuart and Beverly Denenberg, rediscovered Hagedorn’s work in 1983 quite by accident. This American anomaly, whose domestic paramour might be found today in the graphic activism of Sue Coe, comes alive in this small exhibition, which includes the varying styles of this oddball Modernist in paintings on paper, ink drawings, watercolors, and prints.

Green Mountains, Pale Yellow Bolt

1935

Soft Graphite, ink, and watercolor

28 5/8 x 22 5/8 inches

All images by Edward Hagedorn (American, 1902-1982), provided courtesy of Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, California.

The exhibition was organized by Landau Traveling Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA, in association with Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, CA.

Born in 1902, Hagedorn was a lifelong resident of Northern California, but he eschewed mid-twentieth century West Coast landscape painting for the politically-charged sensibilities of Northern Europe. Unlike the East-coast American Expressionists, who were attuned to all manner of European “isms” as they emerged (primarily) from Paris, Hagedorn was closer to his Northern European counterparts Otto Dix, James Ensor, and Emile Nolde both in his forays into the sensual and in his ability to inject tiny, homeopathic-size doses of humor into even the most pessimistic of imagery. Its efficacy on the viewer, when confronted with his menacing personifications of the horrors of war, is at once merciful and unsettling.

While his Germanic heritage no doubt played into his proclivity for the stylistic trappings of Expressionism, Hagedorn showed no interest in aligning himself with any particular group. When the historian Galka Scheyer brought the work of German artists Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlenski, Lyonal Feininger, and Paul Klee to Oakland in 1926 as the so-called Blaue Veir (“Blue Four”), Hagedorn curtly spurned Scheyer’s invitations to join or even show with the group, preferring autonomy to the didactic styles of Expressionism’s subsets.

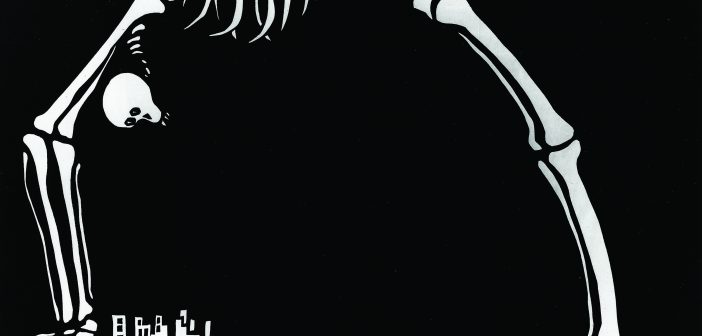

Perhaps the greatest revelation of this show is Hagedorn’s graphic work, produced almost entirely between the years 1925-1935, on the eve of Hitler’s great cultural purge and the mass flight of artists from Nazi Germany. Working deftly in etching, drypoint, lithography, and linocut, Hagedorn created anti-war prints that belong to the legacy of Goya and Dix both in their emotive impact and flawless execution (unlike many artists at the time, who worked in tandem with professional printers, Hagedorn printed his own work.) Medium-sized linocuts of gigantic skeletons representing war are expertly crafted with velvety distribution of ink and economy of carving. In The Rainbow (c. 1935), a skeleton roughly the size of Rhode Island stretches backward to cover a city- not with the calm beauty that follows a storm, but with the menace that precedes it. In the fearful etching Big Boots (c. 1925), a giant skeleton with a saber and Soviet ushanka tramples a crowd. Its long legs and giant feet recall the lanky figures of Feininger’s early work, though the threat of death in the form of bayonets, barbed-wire, gas masks, and sabers place these prints firmly within the history of graphic protest art.

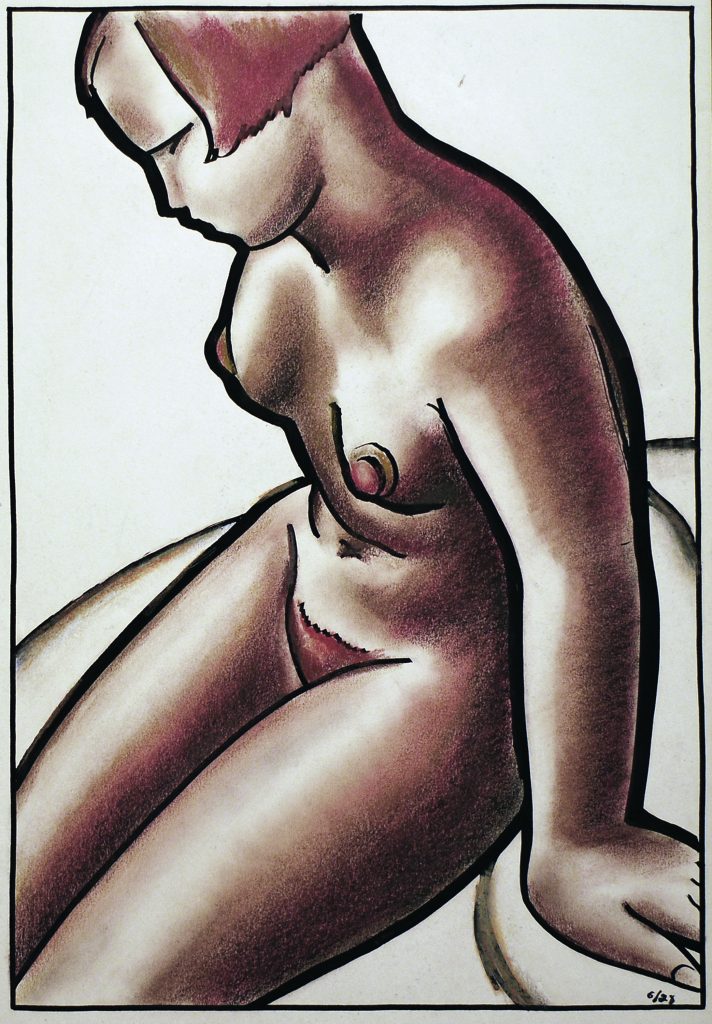

Seated Female Nude 1928

Chalk and ink

18 7/8 x 12 7/8 inches

All images by Edward Hagedorn (American, 1902-1982), provided courtesy of Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, California.

The exhibition was organized by Landau Traveling Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA, in association with Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, CA.

Nearby, a group of paintings serve as a foil for the graphic prints: these paintings celebrate life over death, color over its absence, and mystery over the inimical threat of violence and death. Several landscapes painted in bold purples, yellows, and pinks, depict a private realm between reality and the not-quite-possible. Purple mountains jut out of the Earth with heavy, Beckmann-esque black outlines and short dabs. Several black and white graphite drawings accompany these odd mountainscapes. Obsessive scribbling over heavy black washes give depth and texture to these geological impossibilities while maintaining a graphic flatness. Painted nudes present enlarged sections of the body in bleeding, thinned temperas, creating balanced but unusual compositions that recall Nolde’s watercolors. Warm, colorful drawings of splayed uteri, as if from taken some unholy medical coloring book, are shown on choppy waves or prickly plants. Finally, the curious monotypes of The Crowd (c. 1925), depict small groupings of figures - the meek and horrid bastard spawns of James Ensor’s masked monstrosities and Karel Appel’s loopy, undefined faces - posed as vulnerable sentinels of the unarmed masses.

The Denenbergs’ monograph, while not a catalog to the exhibition, serves as comprehensive guide to an irascible character who virtually disappeared from the scene from the 1940s until his death in 1982. Hagedorn’s work comes as a revelation amid the popularity of recent exhibitions of German Expressionism (there are currently two major exhibitions in the U.S: Edvard Munch and Expressionism at the Neue Galerie in New York and German Expressionism at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art). But Hagedorn’s work refuses to fit snugly into any one category, partly because Hagedorn himself is such an enigma: a West Coast American artist who was more akin to his German contemporaries than to his regional peers. It is a tragedy that so few people are familiar with this work, but given the dearth of venues for this traveling exhibition and the work’s inability to be pigeonholed into any specific style, group, or place, it is perhaps not surprising. Time will tell if, through the efforts of the Denenbergs and a receptive public, we will see more opportunities arise for Hagedorn’s work to get the attention it deserves. In either case, bump this show to the top of your list.

Edward Hagedorn: Volcanoes, Riots, Wrecks & Nudes will be up at the Danforth Museum\School through May 15, 2016.

- The Rainbow 1935 Linocut 9 5/8 x 17 5/8 inches All images by Edward Hagedorn (American, 1902-1982), provided courtesy of Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, California. The exhibition was organized by Landau Traveling Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA, in association with Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, CA.

- Seated Female Nude 1928 Chalk and ink 18 7/8 x 12 7/8 inches All images by Edward Hagedorn (American, 1902-1982), provided courtesy of Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, California. The exhibition was organized by Landau Traveling Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA, in association with Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, CA.

- Green Mountains, Pale Yellow Bolt 1935 Soft Graphite, ink, and watercolor 28 5/8 x 22 5/8 inches All images by Edward Hagedorn (American, 1902-1982), provided courtesy of Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, California. The exhibition was organized by Landau Traveling Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA, in association with Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, CA.

- The Crowd/Two Figures 1925 Oil monotype on thin paper 12 7/8 x 9 1/2 inches All images by Edward Hagedorn (American, 1902-1982), provided courtesy of Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, California. The exhibition was organized by Landau Traveling Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA, in association with Denenberg Fine Arts, West Hollywood, CA.