“Painting is not merely illustration, but real-time communion with ancestors,” reads a wall text in Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia a show at the Harvard Art Museums up through September 18. Spanning several decades of work in a range of mediums, this show’s stand-outs are the paintings on canvas, paper, and bark that read as abstract but are driven by a narrative urgency all their own. They share a commitment to cultural memory and often a seething critique of the colonial project.

In “Emu Dreaming,” a painting by Paddy Nyukiny Bedford, a curving white block occupies a black ground, with one precise reddish circle in the upper left-hand corner. This painting shows the place where, during the Dreamtime, the name for the creation-time inhabited by ancestral spirits, Emu Woman transformed into the cliff face. The red circle indicates the nearby site where, the wall text tells us, in 1920 the artist’s relatives “were poisoned by pastoralists in retaliation for the death of an ox. The bodies were burned on a pyre of wood that the victims had chopped themselves.”

If this is abstraction, it is abstraction that has something to say.

The paintings in Everywhen seem barely contained by the purposefulness of their marks. This narrative made visual, in conjunction with the attention paid to the edges of the canvas, reminded me of the work of Thomas Nozkowski. His practice, on the hinterlands of abstraction, quivers with a communicative urgency and doesn’t seem to just push shapes around a canvas. It is not a coincidence, I think, that Nozkowski has said that all of his forms are drawn from incidents in his life: that while it might not matter to him that the viewer is not always able to read the references, they are the very foundations of what the viewer sees.

In this context, the wall texts put in overtime and then some. Unfortunately, the focus on the cultural practices around the subject of each artwork can come at the cost of delving into the particularities of each artist’s unique practice.

‘Big Cave Dreaming with Ceremonial Object’, by Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, for example, is a gorgeous panel covered in dense tally-like marks. The form on the top, concentric bands in red, brown, and white against a black ground, was described by the wall text as showing a cliff with water and food growing around it. I felt a certain dissonance between what the wall text told me and what I was seeing, not because I doubted the information but because for every shape whose significance was explained, there were ninety-nine I had no context for. Then again, how much could I claim to know from one of the Bosch-influenced prints in the show just next to this one?

Dense concentrations of smaller marks that build larger forms are a feature common to many of the painted works in the show. One of the most immediately striking works is an untitled piece by Doreen Reid Nakamarra. Short yellow dashes form horizontal bars that zip into three dimensions like psychedelic Venetian blinds. The effect is Bridget Riley-like, but without the rote qualities that op art can have.

Rover Thomas, Yari country, 1989. Earth pigments and natural binders on canvas. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Purchased through the Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of Pacific Dunlop Limited, Fellow, 1990, O.7-1990. © The artist’s estate, reproduced courtesy of Warmun Art Centre/© 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISCOPY, Australia.

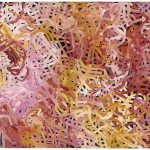

The compositions of other works, such as Rover Thomas’ ‘Yari country,’ draw attention to the canvas border. In Alec Mingelmanganu’s two ‘Wanjinas,’ the figures’ arms run a quarter of an inch from the edge, and their shoulders square upwards as though responding to the right angled corners of the canvas. In Emily Kam Kngwarray’s ‘Anwerlarr angerr (Big yam),’ a four-panel canvas of purples and pinks, the composition seems to want to continue off the canvas. Gulumbu Yunupingu’s ‘Garak IV (The Universe),’ a bark painting of black Xs and white dots, moves the eye around at different tempos in the way a Pollack can.

It’s clear the Harvard Art Museums has made a concerted effort to be reflexive about hosting a show of Indigenous art. The opening, in which Australian Studies Visiting Curator Stephen Gilchrist interviewed artist Vernon Ah Kee, began with a performance on the didgeridoo and a prayer led by members of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), on whose ancestral lands the Harvard Art Museums stands. A series of films centering contemporary Indigenous voices will also screen over the course of the show.

Unfortunately, little emphasis is placed on what transitions across media mean to Indigenous art forms that predate conquest by tens of thousands of years. We aren’t told much beyond the fact that the development of a contemporary Indigenous Australian arts movement dates back to a 1971 community art program in Papunya, led by Australian educator Geoffrey Bardon. Men from the community, some whose work is on display here, first began applying the visual language and stories previously told through rock painting, body painting, and weaving to canvas.

Some art forms that had been extinguished through cultural imperialism were soon transitioned into painting. For instance, the short dashes on the top half of one painting reference patterns of scarification, a practice eradicated by missionaries. What does it mean for art forms to be both preserved and assimilated into painted canvas, and how does this relate to the “eternal present?” Put another way, if all artists, as a precondition for participation in the global art world, are expected to speak English, must all art forms eventually be fluent in Painting?

I wondered about these questions as I looked at Regina Pilawuk Wilson’s ‘Syaw (Fish Net),’ a large canvas of patchy grids of lines against a yellow ground described by the accompanying text as “a painted testament to the now-extinct Ngan’ gikurrungurr technique of twining fiber. By painting the net, Wilson resurrects an object that was once central to Ngan’ gukurringurr life.” Words like “resurrect” and “testament” seem to point towards both an extinction of some traditional art forms and their new life in painted canvas.

Perhaps these are facets of the larger question of how to curate a show around indigenous Australian artists, or any ethnic or geographic identity, for a museum audience. On the one hand, shows like this introduce work to more viewers and situate Indigenous art as objects of cultural value. On the other hand, having a separate show can reinforce an artist’s status as outside the dominant system. If the only way Indigenous art gets into a museum is through shows expressly curated around Indigenous art, there is still a problem.

- Tommy Watson, “Wipu Rockhole,” 2004. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Purchased with funds provided by the Aboriginal Collection Benefactors’ Group 2004, 256.2004. © Tommy Watson/Courtesy of Yanda Aboriginal Art.

- Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, “Two Women Dreaming,” 1990. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Purchased 1991, 91.86. © The artist licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd.

- Rover Thomas, “Yari country,” 1989. Earth pigments and natural binders on canvas. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Purchased through the Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of Pacific Dunlop Limited, Fellow, 1990, O.7-1990. © The artist’s estate, reproduced courtesy of Warmun Art Centre/© 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISCOPY, Australia.

- Dorothy Napangardi, “Karntakurlangu Jukurrpa,” 2002. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. Collection of Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan; Promised gift to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: Spike Mafford © Estate of the artist licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd.

- Emily Kam Kngwarray, “Anwerlarr angerr (Big yam),” 1996. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Purchased by the National Gallery Women’s Association to mark the directorship of Dr. Timothy Potts, 1998, 1998.337.a–d. © Emily Kam Kngwarray/© 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISCOPY, Australia.

- View of the Transformation-themed gallery in the exhibition “Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia” on display February 5–September 18, 2016 at the Harvard Art Museums. Photo: Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- View of the Seasonality-themed gallery in the exhibition “Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia” on display February 5– September 18, 2016 at the Harvard Art Museums. Photo: Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College.