“Horror films don’t create fear. They release it.”

-Wes Craven

Wes Craven, who died on August 30th at 76, was a gentle, avuncular, and piercingly intelligent individual who created films horrific in their violence, sadism, and brutality. Raised in a strict, self-abnegating Baptist family where even movies were proscribed, his earliest memory was his terror of his brooding, raging father who died when he was six. Twenty-seven years later, Craven began to draw on these memories of fear to redefine a frequently dismissed film genre. His films are riddled with portrayals of sadistic father figures, menaced children and teenagers who no one believes, and disseminating, ineffectual parents. At his best, Craven used horror to represent nightmarish Freudian enactments of the crumbling family unit.

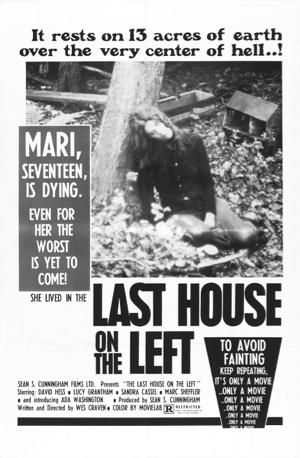

In his late twenties Craven left his Fundamentalist Ohio roots and moved to New York to pursue a PhD in literature. Having never seen a movie except the occasional Disney film, he soon discovered the classics of Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, and other giants of world cinema. As he approached the completion of his thesis, a friend and first-time film producer asked him to write a screenplay. There was one caveat: the backers wanted a horror film, and Craven had never seen one. What he came up with was The Last House on the Left, a loose remake of Bergman’s 1960 film The Virgin Spring, which in turn was based on a medieval Swedish folk tale, wherein a young girl is sent on an errand through the forest and is raped and murdered by a band of herdsmen who, by ironic happenstance, seek shelter at the girl’s parents’ house later that evening. Upon discovering what has happened, the parents exact murderous revenge. In Craven’s version, a teenager and her friend venture into the city and are subsequently kidnapped by a gang of escaped criminals. They are brought to the woods where they are humiliated, brutalized, raped and disemboweled. When the villains end up at the parents’ house, revenge is carried out in blood, chainsaws and oral castration. In mild terms, no one knew what to make of the script. Despite the advertising refrain “It’s only a movie,”1 the film’s wholly disorienting graphic nature elicited outrage and disgust. In an interview, Craven reflected sheepishly, “I don’t think we had any idea of quite what we had done until we went to the theater and saw it.”2 Having no practical knowledge of filming, he hired a cameraman who followed the documentarian’s edict that the camera must never turn away from the action.

This newsreel-style footage has led to readings of Last House as a reaction to the graphic coverage of the Vietnam War and a commentary on the collective guilt of sending America’s children to die in a foreign land. But Last House can also be seen as a commentary on domestic relationships, asking viewers to reflect on how we protect (or control) our children. Do we cloister them within the home, as the parents of Craven’s protagonist Mari would like? Do we render them forever dependent upon us, as the ganger leader in Last House does by hooking his son on heroin? Any resolution to such questions would violate the cardinal rule of horror; there can be no happy endings, and moral lines often blur. After the first prolonged murder scene in Last House, there follows a quiet moment in which the villains look upon what they’ve done in bewilderment and disgust. “You saw the bad guys kind of repulsed… and that angered the audience. They didn’t want to be forced to identify with these people.”3 Craven went beyond his (and the audience’s) comfort zone by writing about things he could not understand, and in doing so shocked even himself. Even by today’s standards, the film still elicits extreme reactions, and it is impossible to remain indifferent upon watching. The inchoate cuts from extreme violence to domestic bliss to the bumbling antics of the cops in pursuit opened the door to a genre-bending, anything-goes attitude with young filmmakers, ushering in the era of the midnight-movie that begat a spate of low budget gore/serial killer/rape-revenge melodramas. This age of low budget exploitation films operated just under the radar of popular entertainment through the 1970s to the age of censorship spearheaded by Reagan and Tipper Gore in the early 1980s.

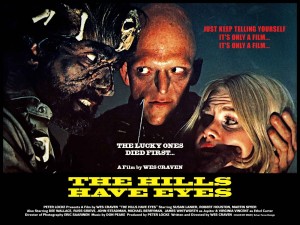

In 1977 Craven used the same guerrilla approach to make The Hills Have Eyes. Headed by a bellicose patriarch, a large family is overtaken by a family of mutant cannibals while driving through an abandoned missile-testing site in the dessert. Craven eschewed the topical theme of nuclear anxiety to focus on family dynamics, wherein the savages are ultimately no less tight-knit (and no less quarrelsome) than the “typical” American family they menace. As the tables turn and the tormented become the tormentors, the audience may find themselves wondering who the real savages are. Craven drew upon several biographical references, including the almost unbearable scene where the mother discovers her dead husband who has been burned alive: “That’s not my Bill,” she repeats over and over, replaying a scene Craven witnessed as a child when his mother stood at his father’s deathbed.

With the proliferation of VHS, these “video nasties”, most of which had extremely limited theatrical distribution (Faces of Death and I Spit on Your Grave, and Texas Chainsaw Massacre, to name a scant few), found new life and a wider viewership. Craven got off to a shaky start as he began making wide-release films, (mostly) due to meddling studio executives’ demands for toned-down violence. The days of the exploitation film were over, and larger budgets meant less directorial control. 1981’s Deadly Blessing might be remembered solely for Sharon Stone in her first roll, while 1982’s Swamp Thing - its dialogue neutered for a PG rating - was so under-funded that you can see the rubber suit rotting away over the course of the film.

In that same year, Craven produced his masterpiece A Nightmare on Elm Street, inspired by a string of newspaper articles about several teenage boys who, after doing everything they could to stay awake, died screaming in their sleep. Truth is considerably more terrifying than fiction, and this was how the razor-gloved, fedora-wearing chatterbox Freddy Krueger was conceived. Named for a kid who used to beat Craven up as a boy, Krueger is the ultimate anti-father: the son of a woman raped by a hundred maniacs (or a hundred bad dads) turned child murderer. He embodies the collective secret shared by the parents of the children of Elm Street who burned him alive. The idea of a dream-dwelling villain was unique, but the idea of a villain exacting revenge on his murderers by tormenting their children is in perfect keeping with the myriad of ways that 80’s films portrayed the disintegration of the nuclear family (Back to the Future, Terms of Endearment, Poltergeist, Mr. Mom, and countless other top-grossing films all speak to this in some way or another). While A Nightmare on Elm Street is a far cry from the stark realism of Last House and Hills, the themes of imperfect parents is clear: Freddy may be the Big Bad, but the parents are the true offenders in their unwillingness to listen, let alone act. Box-office demographics showed that teenage audiences identified.

Freddy exists in a disturbing world where anything is possible: his arms extend to impossible lengths; a sheep runs across an empty room; body bags drag themselves through high school corridors. Such imagery is all the more terrifying for its mundane dream-like plausibility. In a widening sea of franchise-friendly movie villains (Jason of Friday the 13th, Michael Myers of Halloween and Chucky from Child’s Play) Craven created the scariest, and somehow most believable. As checks poured in for Nightmare’s sequels, Craven wrote and directed many other (sometimes mediocre) films with two standouts: 1991’s The People Under the Stairs, about an orphan trapped in the home of a genteel, inbred couple that keep their hoards of cannibalistic children in the basement; and 1994’s Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, in which he cleverly reinvented the tired Elm Street franchise.

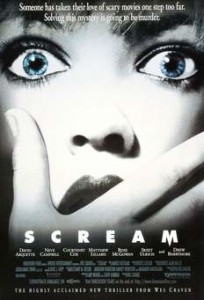

Scream, Theatrical release poster, 1996.

His last commercial success was 1996’s Scream. Probably the first post-modern horror film, it pokes fun at itself as its film-savvy but ultimately hapless teens draw on their vast knowledge of the “rules” of horror movies in hopes of sticking around for a sequel. With its stunning opening and Janet Leigh/Psycho-style offing of the would-be heroin, he once again reinvented the formulaic horror genre with which studios and audiences had become at once complacent and bored, challenging filmmakers to abandon old formulas for new frontiers. Box office numbers from Scream and Scream 2 (1997) garnered major clout with studio executives, particularly the producer-giant Harvey Weinstein, who gave him Carte blanch to make any film he wanted. Craven chose to make Music of the Heart, a drama centered on a classical orchestra staring Meryl Streep. It was a surprising shift away from horror and indicates the sort of films Craven might have made had he not been pigeonholed so early in his career.

Ultimately, Craven was no different from all great directors, which is to say, imperfect. Over the course of his career, he created a handful of game-changing masterpieces, along with many box office flops and schlocky B horror films. Nineteen years after Scream, Craven’s messages are again lost within the Hollywood money machine. Opening weekend numbers at the box office generated by endless horror remakes, predictable “found footage” films, and pointlessly gory, interchangeable torture porn sequels continue to trump originality. Having dismantled the tropes, clichés and inevitabilities of the horror film at least three times, Wes Craven eschewed conventionality, seeing horror film as a medium rife with untapped source material and the potential for social and cultural commentary. In the wake of his passing, we look to new, ferocious breeds of film that shock as they subtly take on such contemporary issues as xenophobia and feminine/gender identity crises. While the age of VHS and late-night grindhouse showings is gone forever, such films can be accessed through Netflix, Amazon and Hulu for the patient viewer sifting through the genre’s endless offerings. Horror, that bastard spawn of civilized cinema and warped mirror to our social mores, has a lot to teach about contemporary society if only the general public had the stomach for it.

----------------------------------------------

1 Theatrical Trailer. The Last House on the Left. Dir. Wes Craven. 1972. DVD. MGM Home Video, 2002.

2 “Still Standing: The Legacy of The Last House on the Left Featurette with Wes Craven.” The Last House on the Left: Collector’s Edition. Dir. Wes Craven. 1972. DVD. MGM Home Video, 2015.

3 Ibid.