Corita Kent and the Language of Pop is a tight survey, focused primarily on the work Kent and other pop artists produced in the mid-1960s. This span of time also maps onto Vatican II, the Catholic church’s ecumenical council that met from 1962 to 1965 to update the church for the modern world. It’s a historical moment that best demonstrates Kent’s position as both an artist and a member of a religious order who united these huge cultural shifts in a practice that supported her own religious life while she worked to bolster her community. The switch to vernacular languages from a Latin mass was one of the largest changes made by Vatican II, but the council addressed a number of issues and codified an updated aesthetic in church services and religious artwork, which encouraged Kent to take on new ground in her role in the art department at the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Los Angeles. The council also worked to bring in fresh analyses of religious texts, right at the moment Kent sought to “take the word and pair it with something visually exciting,” a modern method of creating illuminated meditations on scripture, just as monks had made for centuries.

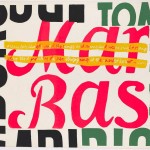

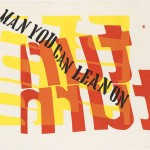

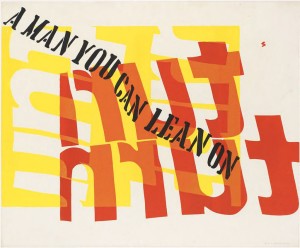

Corita Kent a man you can lean on, 1966. 30 x 36" Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund. © Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles

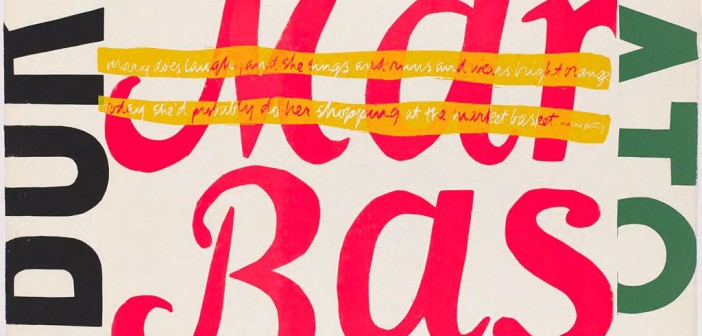

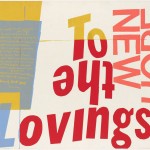

The cultural archive that can be mined in Corita Kent’s work pulls on the rich interconnectedness of the highest and most mundane aspects of culture, religious or otherwise. a man you can lean on is a bold visual take on The Byrd’s “Turn! Turn! Turn!” leading the #1 hit back around to the excerpt the song borrowed from the Bible’s Book of Ecclesiastes. A series of four prints takes a short bit of text from e e cummings (“be/ of love/ (a little) more careful/ than of everything”) and treats it with the weight of a standalone commandment. Elsewhere, a longer meditation on love from the same poet is a scribbled element in new hope, a dedication to Mildred and Richard Loving, who at the time were plaintiffs in the midst of the Supreme Court case that ultimately struck down states’ bans on interracial marriage. Those shifts in scale and the strength of Kent's disparate cultural pairings are united by the fearlessness of her visual style. They are strengthened by the presence of her contemporaries, a setting where her warped and layered texts, bright palette and complex compositions hold up against other artists like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Ed Ruscha who are more frequently celebrated for their commitment to tight visual vocabularies.

A parallel exhibition, Someday is Now: The Art of Corita Kent (organized at the Tang Museum at Skidmore College and currently wrapping up its tour at the Pasadena Museum of California Art), was the first career survey of Kent’s work to bring out the pop art context, but The Language of Pop, with its direct inclusion of works by other artists, clarifies and contextualizes just exactly how adept she was at a cutting edge aesthetic, seamlessly incorporating ordinary subjects and materials in prints that might spark larger radical thinking. What Kent referred to as her “footnote” references—the smaller, denser portions of text that appear in her own handwriting across her portfolio—pull in several writers and thinkers repeatedly, revealing long-term dialogues with works by a range of philosophers, poets, and feminists. These excerpts also draw on personal correspondence with the likes of peace activist and Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan. Parsing Kent’s sources takes effort but feels rewarding, and the gallery text assists commendably in the task. Kent also possessed an uncanny ability to replicate the process of viewing text in a built environment, so that viewer might look, and look again, and then commit to a close reading of those footnotes; an initial urgency slowing down to draw out concerns for social justice or ideas about faith and God. She spoke explicitly about this kind of study in her teaching practice as well, so from an artist-educator perspective it is astounding to see such a direct corollary between her approaches in the classroom and in the gallery.

Films by Baylis Glascock and Thomas Conrad loop in two locations in the gallery. One shows films from the 1964 and 1965 Mary’s Day celebrations at Immaculate Heart, the other footage of Kent in the studio and in a lecture setting. The sound is low, unfortunately, but both sets of films are worth a little extra effort for Kent’s narration. More of this kind of material can be seen in a small but worthwhile secondary exhibition in Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library. It includes a variety of archival materials: letters, sketches, students’ work, as well as additional prints and documentation of commissioned projects.

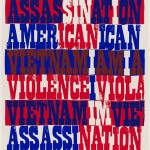

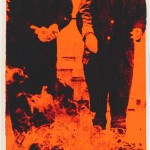

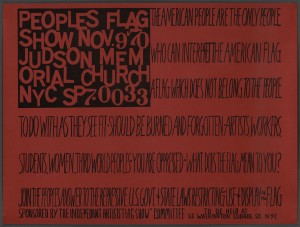

Faith Ringgold Peoples Flag Show Nov. 9 '70 1970. 18 x 24" Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of William S. Lieberman © Faith Ringgold

There are other excellent selections in the main exhibition beyond works from Corita Kent. With a female artist at the center of the show, more women are highlighted throughout than might be otherwise. Though they are still outnumbered by the many men who dominate the history of pop art, artists like May Stevens and Marisol are given real weight here. The best of these connections appears in a small selection of works that focus on the American flag. Kent’s american sampler serves as the jumping-off point for the inclusion of works by Jasper Johns, William Copley and Robert Indiana, but the selection lands spectacularly on two Faith Ringgold posters. The first promotes the People’s Flag Show and includes text written by Ringgold’s then teenage daughter, a short piece of writing considered so inflammatory the show’s organizers were charged with desecration of the flag. It is followed by the Judson 3 print of a U.S. flag in pan-African red, black and green, which Ringgold created and sold to cover legal defense.

Perhaps Kent’s vocation as a nun made her practice seem less formally oriented and contributed to art history’s neglect of her work, in a manner different and more pronounced than other female artists who go underrepresented. Corita Kent did intentionally shirk the term art, framing her creative practice within her religious life and her teaching, as opposed to a body of work that would ever stand separate from her or her values. She left her order in 1968, in response to mounting pressure from the local archdiocese that felt she and the other nuns had already overstepped the modernization laid out by Vatican II. Kent continued her work, relocating to Boston, working with a printer, and incorporating more overt anti-war sentiments into her prints as conflict mounted in Vietnam. At one point she borrowed a Balinese saying, “We have no art, we do everything as well as we can,” and she maintained that as a guiding principle, zeroing in how art can embolden viewers in a changing political landscape. With a fresh read, her commitment to holistic methods points to a hybrid of physical artmaking and community engagement that artists today are striving for in the domain of social practice. Kent sets a badly needed precedent for how one might engage with the world.

An artist’s ability to shift contexts and assemble new meaning from disparate fragments can feel whip-smart for a viewer as the work leads them through those leaps. That reaction seems to have diminished in current readings of pop art strategies, which may just be a product of burnout on the viewers’ part. The use of commercial signifiers in visual art has turned sometimes painfully, uselessly cynical while the general public’s media literacy has grown more nuanced in the intervening decades, leading to an exceptionally flat reading of a Campbell’s soup can or Claes Oldenburg’s plastic lunch. From this perspective, fifty years out feels like an exciting time to reexamine the open-ended works of a pop artist who tilted so fervently towards goodness.

- Corita Kent new hope 1966. 30 x 36″ Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund © Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles

- Corita Kent bread and toast 1965. 16.75 x 26.5″ Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund © Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles

- Corita Kent mary does laugh 1964. 30 x 40″ Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund © Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles

- Corita Kent american sampler 1969. 22.5 x 11.5″ Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund. © Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles

- Corita Kent a man you can lean on, 1966 30 x 36 in. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund. © Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles

- Corita Kent phil and dan 1969. 22 1/2 x 11 7/16″ Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund © Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles

Corita Kent and the Language of Pop is on view through January 3, 2016 at the Harvard Art Museums.