The conversation between host and visitor is the art. He and other hosts bring in interesting objects that could be considered compelling in their own right, but Lee didn't put his name to these events so you can look at the objects. He is interested in how two people can interact when they are impelled to talk to each other, even without knowing each other.

Contemporary art comes in many flavors and Lee Mingwei's work can be over-simplified as a post-studio, social performance. His work obviously isn't strictly visual art, as social interactions are not visible. His kind of performance is not an active, studied dance or some form of brutal endurance test, but instead is an inviting encounter and seems more like our everyday experiences than a constructed display.

Lee's work that relies on conversation is deceptively simple as you are really having a conversation with someone. It's probably closer to a theatrical experience where the action activates your awareness of being with the performer, but the host isn't playing at being someone that they are not. While reviewing The Living Room for the New York Times, Deborah Weisgall said, "It is not quite a natural conversation. It is more intense, more self-aware." The awareness of how you are talking, how talking functions, is just one layer of experiencing this project first-hand. The transaction of chitchat—somewhere between small talk and getting to know you—is the thing to consider and retain.

Creating a connection between two people is evident in most of Lee's projects. For 2003's Harvard Seer's Project, he made a divination space in Memorial Hall that was run by astrologers, card readers, and other people from Harvard's community that were skilled in divination.1 He activated not only the people seeking information but he also revealed that there are people who use these tools everywhere. His Letter-Writing Project asks people to write something they've always wanted to write but didn't have the time to finish.2 This project asks visitors to really consider, even if it is painfully self-conscious to do so, if they really want to write down these things and gives them the space to finally do it. Being that there is a good chance that your note will only be read by a few people—certainly fewer people than would read the average Facebook post—the author is free to write down the truth, to confess and move on. The other subtlety to this project is that the environments for letter writing cause the writer to sit, kneel or stand, which are all meditative positions in Chán Buddhism.

The ongoing nature of The Living Room is evident in its location. Named after Lee's project, the room now known as the Richard E. Floor Living Room was created in consultation with Lee. The way that the Gardner takes care of its artists in residence is also part of this story. While some residencies cost the artist money and are effectively a partially subsidized vacation from the norm, when an artist is invited to the Gardner they are granted the time and space to create, and access to the comfort that Isabella was once able to afford. Lee has related the story of proactively coming to the Gardner with a preset project in mind but found that by relaxing through swimming at the Y, rollerblading around town, and having access to the Gardner Museum's archive gave him the space to reconsider that initial plan. He found himself interested in Mrs. Garnder's role as host.3 That unanticipated interest in hosting and providing for others generated The Living Room.

•••

Lee MIngwei I've been coming back, this is probably the tenth time, I think one thing very unique about the Gardner Museum is that they stay very close with their alumni, the artists in residence here. And for me, its really a growing process. It's great to be back and see the new part of the building.

John Pyper They say you've been here six times officially so far.

LM For this project, yeah. After the show opened, actually before the show opened I came back to do something, and I've been back and forth just to visit.

JP How has it changed over that time? Clearly it can't be the same thing, and it sounds like it's probably one of your longest projects?

LM You mean The Living Room? When I first did it in 2000, because the show was, I think two and a half months, so I figured that every other day there was a host, but this one is very different because it is stretched out to—I don't know how long—so clearly it's impossible to have to have hosts here every day. So, that's why I say: let's do it two days a week, and it doesn't have to be the same host, it can be a different host; so that's, clearly, because of the time and availability that we changed the original part of the project which is not continuous.

Besides from that, another thing that changed, the room is different, the original room was the contemporary space, over there, which is not longer in existence. I just turned it into a contemporary modern living room. This room is so different, in terms of ambiance and I tried to keep some elements to be very contemplative; birds in here—which calm me down at least—and the roll of the seat back there facing the garden and the Gardner, I asked Renzo Piano, that's very very important for people to be able to look back into where we all came from. that part of old history, and I'm so glad that they kept it that way. It was great. I guess that's the only... and also the size of the object that people brought in this time is much smaller in scale.

JP Yeah, there was a motorcycle in the original one, right?

LM Yeah, and also a Brancussi sculpture, and these are very large things. So because of the circumstance we asked people to bring things that we don't need a little bobcat to move around.

JP Right! For your own practice, where did this come out of? For yourself, I think most people won't question when someone who draws, draws, but we become very aware of the performance, especially when it's a non-object. So where did this come from for you?

LM I grew up in Taiwan, and then later on immigrated to San Francisco when I was about thirteen. But before that every summer, my father who was a doctor he asked me if I would like to spend some time in a Zen monastery. Because, at that time, I don't know why, I was spiritually inclined I just liked to go to church, temple, mosque, and whatever. So he said, "Well, would you like to go study with one of my patients, who is a very well known Zen Buddhist monk?"

I said sure, and went and stayed there for about a month during the summer. That's when I really, started looking into... or my teacher really taught me the idea of attention, and also that things are impermanent. So that having objects like this, it's really an illusion for myself that everything is permanent. So he tries to steer me away from that, by doing, for example, we'll go walk on the sand in the garden, the rock garden, and after that he would actually ask me to make as little impact as I can when I walk, which is impossible. But by doing that, it gives me a very hyper-sensitive feet when I step onto the sand and the temperature, each grain; it's really quite amazing because I didn't want to make an imprint. So from that training of something that is, everything is impermanent, my work has that element built in.

Originally, I was actually trained as an architect and also in biology, but I feel that I want to be in a field that has no absolute answer, no right or wrong, and also something that has original ideas. Originality. Also, when I went to school in California, quite a few of my teachers studied with a Zen master called Suzuki in the 1970's and their practice was highly influenced by him, so it really all makes sense that I start doing this type of work. Also, I wasn't very good at making things. I wasn't good at drawings. I failed my color class. It was terrible.

JP I think we've all been there.

LM Life drawing! Oh my god, this is terrible... So I really wanted to be an artist, but I failed these standard classical training class. So my professor said not to worry, there are other ways of being an artist, so he introduced me to Allan Kaprow's writing, Beuys's work.

JP You're based out of New York now?

LM Yes, I'm based in New York.

JP So being the way your practice is, do you have a studio?

LM I don't. I really don't. So when people say, may I come do studio visit, I say...

JP We're doing one now!

LM Exactly! I could do it anywhere, because this is my studio here! I really don't have a studio. But I do have installations and objects that are part of my work.

JP At the Smart Museum, you did the eating project—the four tatamis, the black beans—I guess in someways, you can run into the problem where your work is completely ephemeral, but once you do some stage craft to it, do other people try to force those objects as art objects upon you?

LM I think that these days, people are—well, at least in the contemporary art world—people are well versed enough that they try not to make that as an art object. Because clearly that was a stage, that wasn't really the art, that was a stage where these things happen. It's almost like you saw a performance of Pina Bausch at Joyce Theater and try to make the Joyce Theater the artwork and not Pina Bausch's work. So people are sophisticated in that way already. These platforms, or these tools that you see in my other projects, usually I would design them with an architect and then fabricate them with a fabricator I've been working with since I was at Yale. So he has a studio at Yale and fabricates these things for me. Eric made that platform that you saw at Smart, and the way we designed it is that it could be taken apart and reused again so that's not just a one time usage. So, as you know the project is traveling to other institutions, to Blaffer, to SITE Santa Fe, and other institutions, so this will be traveling

JP So, what about the relationship to the performers that come in for you, for lack of better word.

LM I was just talking to somebody about this. I always need other people to come in and do the project. It's not about Lee Mingwei doing the mending for you or Lee Mingwei sleeping with you. It's more about strangers doing this task with another stranger. So it's quite different than, you know, it has to be Marina Abromovic staring at you there at MoMA, nobody else can do that. But for all my projects, it's not about me doing it. It's about someone giving a gesture of gift-giving to another stranger, so that's completely built in to the project, that someone else will be that.

JP That there's that transaction between two people.

LM Mm hm, that it doesn't matter if it's Lee Mingwei, or Mike, or John.

JP The other thing that I've noticed is that you've said your work is commercially unfriendly, it seems that the work is institutionally friendly though.

LM Most of these are commissioned by institutions. I'm very grateful that there are institutions who are willing to really give me the chance and explore what it is to create these ephemeral projects. I think every single one of these projects were commissioned by institutions. When the institutions don't know what they are going to get. They just say, Mingwei, come in, spend some time, and then come up with some idea. It's not like they say do a project about living rooms. And interesting enough, when it's commercially so unfriendly like that, some collectors actually were able to collect these things from institutions.

JP To turn them into objects?

LM No actually, they acquire the rights to perform them. So they don't really acquire the objects, because the objects are really the stage. So usually, if they want to restage this particular project, they will do an exhibition copy of the original platform. Like the mending project, the table and the spools.

JP It's interesting being a non-studio artist, that without having that simple definition that "my media is" that you've ended up being an additive artist. That you've ended up adding things to the definition of art.

LM I often think that I don't even know what art is, because I like the idea that everything can be a possibility of... how can I say it? That everything is art, but everything is not art for me. That it's up to other people to define what this is in their lives. So what I'm doing here is just an event, and people might consider that art because it's in a museum, they walk away, and I think my current thinking is that they walk away with a question, of what was that? If they walk away with their questioning me, I'm very happy already; about my work; about what it's all about.

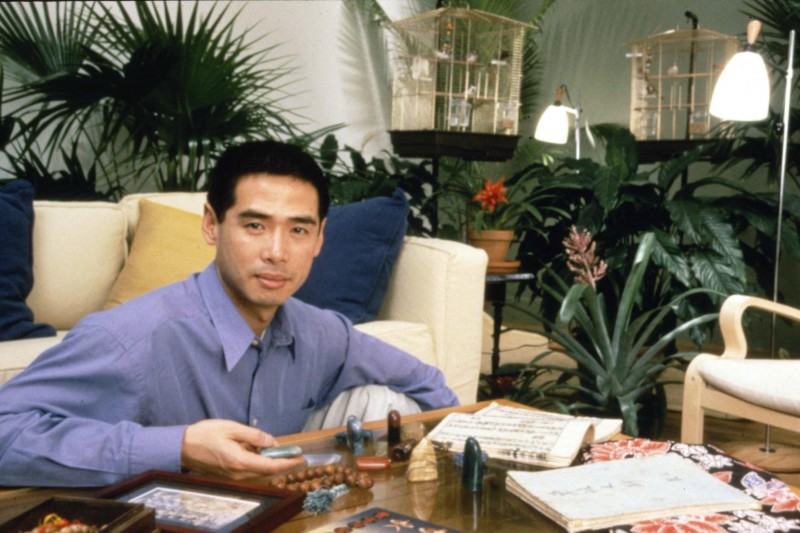

- Lee Mingwei, Host in The Living Room Project, 2000. Photo: Anita Kahn Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

- Lee Mingwei, Host in The Living Room Project, 2000. Photo: Anita Kahn Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

- Lee Mingwei in the Courtyard, 1999. Photo: John Kennard Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

- The Richard E. Floor Living Room looking towards the original portion of the museum. Photo courtesy of Nic Lehoux, Renzo Piano Building Workshop

- Lee Mingwei holding a conversation. Photo courtesy of Cheryl Richards

[1] Ken Gewertz, "Is this art?: Lee Mingwei says, 'Trust me.'," Harvard Gazette, 1 May, 2003, http://www.news.harvard.edu/gazette/2003/05.01/16-seers.html

[2] The Letter writing project at the Fabric Workshop Museum.

[3] Artist page on the Isabella Stewart Gardner website