When I first moved to Orlando in 2011, a neighbor mentioned that I should visit the "ugliest building" in town. She did not know about my affinity for architectural underdogs; a colleague once suggested I start the "National Ugly Building Society." I knew I had found a downtown treasure when I laid my eyes upon an enormous, striated concrete structure—the 1966 Orlando Public Library, which I later discovered was the first library designed by noted modernist architect John Johansen.

Surprisingly, when the citizens of Orlando outgrew the poured-in-place Johansen structure (finished at a mere 60,000 square feet), they voted in a $22-million bond issue to raise funds for a 230,000-square-foot addition, in a style similar to the existing building—all concrete, from the floor to the roof, and in prime Brutalist form. This addition, designed by local firm Schweizer Incorporated in 1986, has since undergone a series of interior rehabilitations, while keeping the original style of both buildings intact. At the grand opening, L. Duane Stark, design architect at Schweizer, observed "The building projects the image of a well-studied piece of life-scale sculpture, and few who see it remain unmoved." The enormous structure, which now fills an entire city block, is far from the worst building in Orlando (you can only imagine some of our lesser examples), but it is a remarkable representative of a restored, lively Brutalist design that continues to captivate—and confuse—the public.

Unfortunately, the expansion and restoration of the Orlando Public Library is the exception and not the rule. Johansen’s work has been taking a beating for decades. One of the "Harvard Five," a group of Connecticut-based architects that collectively led the field with innovative designs in the mid-twentieth century, Johansen created a series of concrete buildings that are assertive, solid, and intimidating. Way back in 1988, at almost the same time that the good people of Orlando decided to keep their library, talk-show host Phil Donahue demolished Johansen’s one-of-a-kind Labyrinth House in Westport, Connecticut, calling it an "avante-garde bomb shelter," that collected fast-food wrappers and "lovers and other strangers at midnight." Built in 1966 for Dr. Howard Taylor, the 3,100-square-foot concrete house was known for its "juxtaposition of surfaces" and textural contrasts between the interior and exterior. Willis Mills, then president of the Connecticut Society of Architects, defended the site as "a seminal work by one of America’s most original and creative architects." But never mind all that. Donahue backed his decision, saying "Where were all these caring people when the building was empty? I’m supposed to have some moral obligation to a house nobody wants to buy?" He failed to mention that he had only owned the house for two months, and made plans for demolition without any knowledge of its historic significance. When informed of the architectural misdeed, Johansen replied "It’s like a death in the family. Mr. Donahue has a right to his taste, but ownership is a responsibility and not a power over everything."1 Apparently the owners themselves see it differently—at least two other major Johansen designs are currently being considered for demolition: the 1970 Mummer’s (Stage Center) Theater in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and the 1967 Morris Mechanic Theater in Baltimore, Maryland.

These outstanding buildings should be celebrated, not denigrated. Concrete is an ancient material (first utilized by the Romans) that is flexible, durable, and infinitely "plastic." Architects unleashed their imaginations during the Brutalist period, creating columns, cantilevered balconies, sun screens, and staircases of concrete, following contemporary design leaders such as Le Corbusier in France, but also expanding on earlier experiments conducted here on native soil. The concrete revolution was championed early in the century by luminaries such as inventor Thomas Alva Edison, who owned a Portland cement company and developed plans for a cast-concrete house that he hoped would transform the way architects designed and constructed buildings. In a 1911 handbook, Edison proclaimed that "the age of concrete has started and I believe I can prove that the most beautiful houses that our architects can conceive can be cast in one operation in iron forms at a cost, which by comparison with present methods, will be surprising. Then even the poorest man among us will be enabled to own a home of his own—a home that will last for centuries with no cost for insurance or repairs, and be as exchangeable for other property as a United States Bond."2 If he only knew that today even the sturdiest and most sacred structures are considered disposable. Edison’s company supplied the concrete in 1923 to build the once-treasured Yankee Stadium in New York, which hosted more than 6,500 games before its demolition in 2008.

Regrettably, too many of our Brutalist masterpieces are on the "maybe" list, including notable buildings and landscapes across the country: from Sarasota, Florida (Paul Rudolph’s 1958 Sarasota High School addition), to Chicago, Illinois (Bertrand Goldberg’s 1975 Prentice Women’s Hospital), to Minneapolis, Minnesota (M. Paul Friedberg’s 1975 Peavey Plaza). All of these sites are heading toward their inevitable date with the bulldozer unless we—architects, planners, preservationists—can propose practical and profitable ways to keep the structures in place while increasing public appreciation for a relatively obscure moment in architecture. In these cases, more than any other, advocates for the sites will have to expend a good deal of energy fighting the "eyesore" label, a favorite pejorative of critics, the press, and pretty much everyone who has a strong opinion about architecture.

Most importantly, this tsunami of demolitions exposes a host of critical liabilities in our historic preservation programs and policies, both private and federal. First, no one is keeping track of the numbers; not how many outstanding Brutalist buildings we harbor, nor how many we have lost. A building disappears here and there, one or two or five per year, without much notice. The cumulative result is a steady disintegration of our cultural heritage collection over the decades, an irreversible erosion of our twentieth-century architectural story. And, with the exception of a few earnest, but isolated efforts, nobody seems able to stop it because, essentially, the idea of renovating and re-using old concrete buildings perplexes the public. People, as a group, find it difficult to look past the problematic issues (often present in any older structure), and prefer to focus on the reasons why a building doesn’t work, instead of an objective analysis of what the building can do for us, with a little care and a lot of imagination. Additionally, city leaders are often timid when faced with their concrete past; many of these structures were designed and built during a difficult period in American downtowns, within the historic context of inner-city riots, economic downturns, the turmoil of the Vietnam War, and the struggle for civil rights. Second, the process of designating a building as historic relies heavily on whether the structure has reached fifty years of age; less than that and the building must demonstrate "exceptional significance," to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Yet, most of these buildings never reach that point, with a number of structures—like Johansen’s Labyrinth House—razed within thirty years of construction and before scholarly research can catch up to this arbitrary timeclock.

If the twentieth century was the "age of concrete," according to Edison, maybe the twenty-first century will mark the renaissance of this much-used and frequently maligned material. The Getty Conservation Institute recently sponsored a Colloquium to Advance the Practice of Conserving Modern Heritage, drawing more than sixty historians, practitioners, and conservators from across the world to Los Angeles to debate and discuss the future of modern movement buildings, including Brutalist landmarks such as Boston City Hall, designed by Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles (1963-68), or Robin Hood Gardens in London, built in 1972 by the husband and wife team of Alison and Peter Smithson, acknowledged leaders in concrete construction and "New Brutalism" in Britain.

A few Brutalist buildings have already undergone restoration and a revival of sorts. Paul Rudolph’s 1963 Yale Art and Architecture School in New Haven, Connecticut, nearly met its end until the current dean, Robert A.M. Stern, fought to save his predecessors work. In 2008, the school invested $126 million to restore the building and construct a major addition designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates. Marcel Breuer’s 1961 Saint John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota, is a majestic, contemplative space created for its Benedictine residents; the all-concrete church is undergoing increased scholarly analysis with at least one new book on the campus design expected in the next year. And Rudolph’s 1971 Orange County Government Center in Goshen, New York—known for its eccentric eighty-seven separate roof sections—was recently saved at the last minute by a vote to rehabilitate the building rather than replace it.

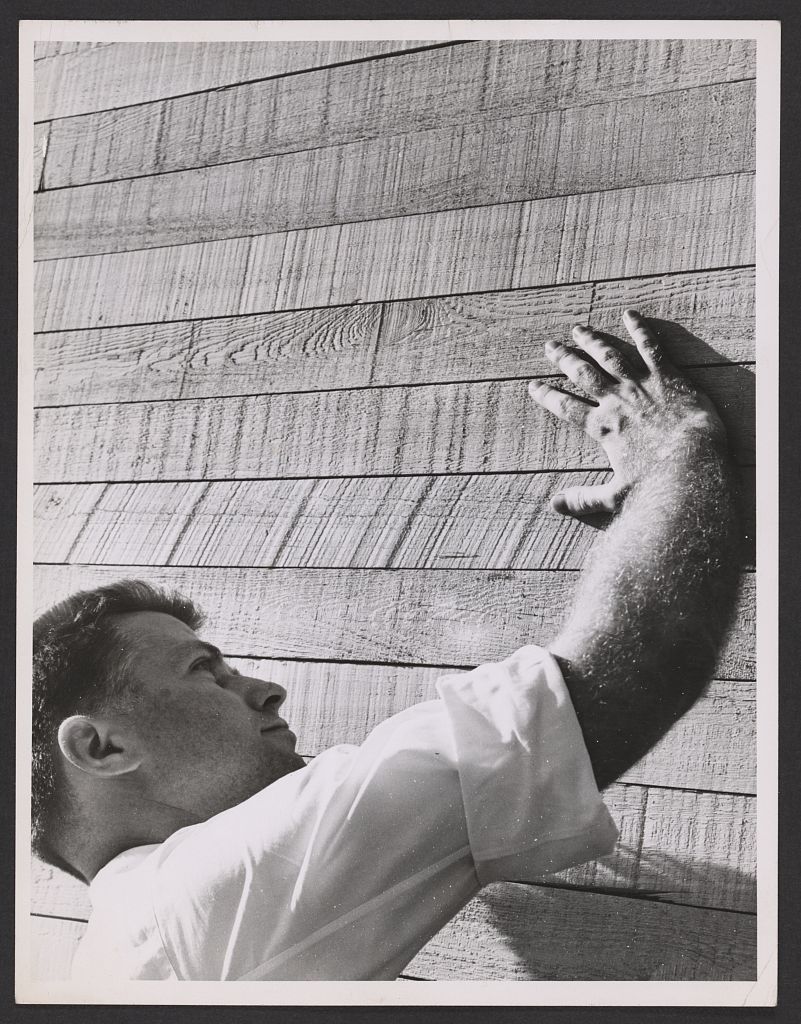

I admit that a Brutalist building doesn’t shout out "hug me" to the casual passerby. The raised, rough-edged corduroy pattern would scrape the skin off your elbows. But, there is a material sensitivity if one looks intimately. Seriously, get close—really close—to your neighborhood concrete. You will see striations, stripes, swirls, wood grain, and even splinters embedded in the textural crevices. Take some time and observe how the sun and resulting shadows change the façade’s character, or how the light penetrates the interior in tightly controlled, meaningful ways. Follow Rudolph’s lead: A period photograph of the architect held at the Library of Congress depicts him softly caressing a board-formed wall, his hand and eyes delicately exploring the multiplicity of fossil-like wood imprints on the surface of the concrete.

This idea of loving, and living with, Brutalist buildings as Johansen, Rudolph, and others promoted is catching on again, particularly in the northeast, where perhaps the greatest concentration of these structures and landscapes occur. A trio of architects in Boston began their own advocacy campaign under the moniker of "Heroic Concrete" to better express their vision of what these buildings represent, highlighting the "New Boston," in a series of events and exhibits accompanied by a survey of local concrete buildings built between 1957 and 1976.3 The strictly black-and-white blog "Fuck Yeah Brutalism," is gaining currency as an international gathering place for fans of the much-maligned style, featuring dramatic photographs of buildings from Scotland (James Stirling’s 1964 Andrew Melville Hall at the University of St. Andrews) to Uruguay (Nelson Boyardo’s 1962 Columbarium at Northern Cemetery, Montevideo). And Archinect, a design networking website, provides the perfect opportunity to announce your allegiance to all things concrete: a T-shirt (appropriately modeled by a tattoo-sleeved gentleman) emblazoned with "I Heart Brutalism."

Johansen, who died recently at the age of ninety-six, never understood the destruction of his buildings. Why would one destroy art? He did provide solace to preservationists with these words, however, inscribed on his website: "The reward is in the doing; I won already for having created it. I offer finally a more forceful reference: forgive them, for they know not what they do." As one who has fought for the future of a number of modern buildings, and occasionally lost, I second those thoughts. Architectural design is cyclic; an entire generation of Americans went to school, attended church, paid their traffic tickets, and served on juries in Brutalist buildings. Saving these buildings is about more than keeping a structure upright; it is also about saving people’s stories and understanding our own contributions to history.

- Paul Rudolph circa 1960 getting close to concrete. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

- The Schweizer addition to the Orlando Public Library Christine Madrid French, 2012

- The Schweizer addition to the Orlando Public Library Christine Madrid French, 2012

- The original section of the Orlando Public Library. Ruben Madrid, 2013

- Schweizer’s design for the staircase in the Orlando Public Library Ruben Madrid, 2013

[1] Victoria Balfour, "TV’s Phil Donahue Demolishes a Unique House and Perhaps His Reputation as Mr. Nice Guy," People magazine, June 27, 1988, vol. 29, no. 25. Nick Ravo, "Eyesore or Landmark? The House Donahue Razed," New York Times, June 10, 1988.

[2] Myron Henry Lewis and Albert Hotchkiss Chandler, Popular Hand Book for Cement and Concrete Users: A Comprehensive and Popular Treatise on the Principles Involved and Methods Employed in the Design and Construction of Modern Concrete Work, New York: The Norman W. Henley Publishing Company, 1911, 89.

[3] http://www.overcommaunder.com/heroic/