Editor's Note: This essay was written in reaction to Harvard Art Museum's re-opening on November 16, 2014. Kayla Hammond Larkin responds to the event of a major museum reopening to the public, the Harvard Art Museums collections, as well as the museum's place within the community. This is the first of two articles to examine Harvard Art Museums.

Six years can feel like a very long time time -- even in Harvard Square, where in the expanse of just a few city blocks, you can tread over the site of a brunch George Washington once enjoyed during his Revolutionary encampment, and then stride past the former home of Longfellow’s ear-nose-and-throat guy. But six years, even here, can truly make all the difference. In six years you can still create, if not something out of nothing, then perhaps something that is greater than the sum of its parts.

I have lived in and around Harvard Square for the better part of a decade, and during this time I have watched the Harvard Art Museums -- the Fogg, the Sackler, and their teutonic cousin the Busch-Reisinger -- coalesce into the $350 million complex that stands before us today, renovated and expanded under the aegis of the famed architect Renzo Piano. At long last the museums, now housed under a single roof, opened to the public in November -- with some things old, some things new, some things borrowed, and some things from Picasso’s Blue Period.

During the time it took to complete the space, I regarded the progress of the museums with equal parts tenderness and annoyance, because all the clamor and rough edges of their becoming something seemed to be in step with my own sense of becoming something. Over the course of six years I went from muscling my way through Quincy Street construction zones with late term papers in hand to gingerly maneuvering a baby carriage through the forest of orange fluorescent mesh marking the detours down Broadway.

But maybe this is all as it should be. By all accounts, the promotion of growth and advancement factor prominently into the mission of this institution. In addition to the galleries, much of its upper echelons are given over to an art study center and a conversation lab. Climbing the the narrow staircase at the spine of the complex is like a dream -- not in the sense that it is a particularly sublime experience (though the glass ceiling doesn’t hurt), but in the sense of one dream in particular: that dream where you discover a room in your house that you never before knew existed. On my way back down from the fifth floor, a man on his way up nodded at me and asked, breathlessly, "What’s up there, besides the books and stuff?" I told him that it was mostly just the books and stuff. He turned around and walked back down the stairs.

The wall text functions with the clerical accuracy of birth certificates, ignoring colloquial use in its insistence on listing the artists’ names in full. I did a double take when presented with works by " Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas" and "Pablo Ruiz Picasso." Even the cafe experience appears to have been designed with teachable moments and betterment in mind. Featured prominently on the menu are brussels sprouts (!) and cauliflower (!). When I asked for a bottle of water, I was informed by the staff that while they could not honor that particular request, what they could offer me was a more environmentally-friendly box of water.

I’m not sure how worried I should be about whether a cultural institution is too concerned about helping you learn to concern itself with helping you feel, but that’s the thing about Harvard. "Excellence without a soul" was the phrase used to describe the university’s particular problem by former dean Harry R. Lewis in his 2006 book of the same name.

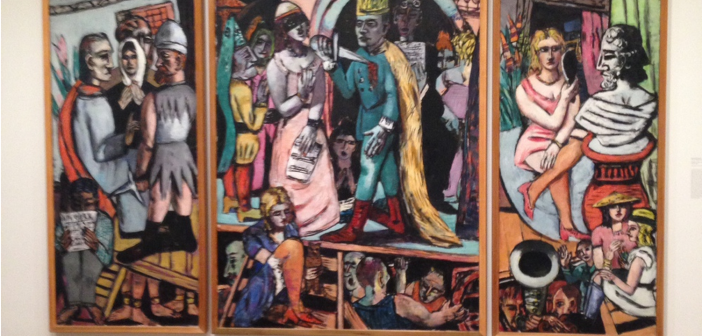

But much to my delight, from the moment I set foot inside the Harvard Art Museums, I knew that someone -- some invisible hand -- was trying to move me. The first painting visible to a museum guest from the Quincy Street entrance is the center panel of Max Beckmann’s triptych Actors (1941-1942). Let me be more specific: the first thing you see upon entering the museum is a sort of Day-Glo cartoon king stabbing himself through the heart with a stake. Of the 250,000 objects in their combined holdings, this is the first thing that the Harvard Art Museums want you to see. Talk about sight lines.

Beckmann (1884-1950) painted Actors while in wartime exile in Amsterdam as he faced the threats leveled at practitioners of the avant-garde by nationalists in his native Germany. The tragic king at the center has been identified as Beckmann’s self-portrait. Just look at it, and see how you feel.

As I followed the trail of the walleyed mid-century Germans to see Actors up close, I overheard two women on a friend-date discussing the guests at a dinner party they’d both recently attended. "Who was he, again?" asked one, studying a wall panels that outline the history and distinctions between the various movements represented in the gallery. "He was the guy," said the other, laughing lightly, "who had too much to drink and started crying."