When the work of a former graffiti artist enters the hallowed white box of a museum, almost inevitably there will be cries of "Judas." Yet another in the ICA Boston's string of exhibitions dedicated to street, or "outsider" artists, Barry McGee joins the recently surveyed Os Gemeos, Dr. Lakra, Shepard Fairey, and a mural by Swoon, all following the triple bill of Street Level: Mark Bradford, William Cordova, Robin Rhode in the years since 2008.

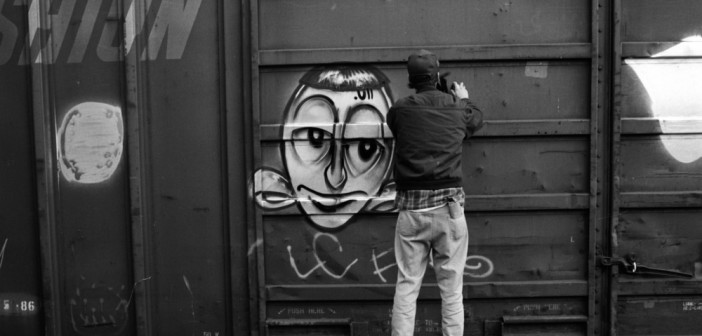

Much of the public backlash comes from the disconnect, which seems at least outwardly to be obvious to everyone but those involved, between the artists' original motivations and the flourishes presented in the institution. McGee's mid-career retrospective occupies the main galleries and has spilled out into the real world with two large blue and red tags behind Fenway Park—an entirely legit graffiti facilitated by the ICA and executed by Josh Lazcano, aka Amaze, and other members of McGee's crew. In Beautiful Losers, a 2008 documentary about McGee and his peers, he explains the power of the individual tag: "You can look at something for half a second and know the style, the risks the tagger took, everything; it's all condensed into one three-and-a-half-second movement. That's what I like about it. It doesn't have the glorious trappings of the art world. A kid's tag is a kid's tag, that's it." Within the museum, where shows are scheduled and designed years in advance, one can't argue with the claim that graffiti's spontaneity, and moreover its unsanctioned appearance, is lost.

But systematically scorning street art's adoption by the institution has become too predictable a reaction not to be questioned. So how does this exhibition, since that is what it is, hold up as an exhibition? What do McGee's works gain from being grouped into a chronologically ordered context? What particular gestures does the artist propose for this location, and how do the works originally intended for the street adapt to the space?

Barry McGee

Untitled (Crawling Man), 1999/2012

House paint on tin galley trays mounted on plywood

77 1/4 x 68 x 132 in.

Private Collection

Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

The overall mood of the show is profoundly sad, and, beneath the high sheen and reverberant color, each gallery in its own way reeks of loss. The losses are multiple: human, technological, artistic. Some are clearly addressed, others seem less intentionally present but cling to the air like the noxious smell of aerosol. Part of the retrospective presents a museum of the artist himself: Craig Costello's black and white photographs reflect a time of poverty, risk-taking, and marginal living. Stripped and rusted spray cans crowd together on the wall next to the trappings of the graffiti artist—his jacket and bolt-cutters. A wall stained the color of chewing tobacco displays early untitled drawings grouped into one of McGee's characteristic frame-clusters (a gesture now so ubiquitously present in hipster design magazines, it's hard not to smile). The contents of the frames are worth a closer look. And this can be said for all of the work on view: the guy can draw.

In the second, larger gallery I did a double-take—no doubt, exactly what McGee intended when he stood an automaton on a trashcan, hoodie-clad and mid-tag. Once you realize the tagger isn't flesh and blood, that the installation isn't still in progress, that the aerosol isn't really spraying, the sadness becomes overwhelming. That's when the mosaic of letterpress galley trays covering the wall begins to look like so many plaques in a mausoleum, and the exhibition takes a decidedly morbid turn. The animatronic taggers mimic a gesture in a closed, mechanical loop of non-productivity. Rooted in place, there is nothing furtive about the act: they are literally going through the motions, not unlike the wax recreations of the Madame Tussauds international franchise.

Death is directly addressed through the intimate exhibition of Margaret Kilgallen acrylics, McGee's late wife and artistic partner, protected inside a thick bunker of galley trays, whose entrance has been roped off from prying eyes. One of the best drawings in the show occupies a side of the edifice: a man crawling on his knees and elbows, in a gesture of prayer or exhaustion, sweats paint. These sculptural installations aren't the effort of a "street artist"—a term McGee says scares the living daylights out of him—but those of an artist plain and simple, whose past as a tagger, printmaker, and sign-painter informs the content and style of his work today. And there are other influences too. McGee's carved wooden figurines, reminiscent of early Christian statuary as much as folk art, are animated into tagging minions of various sizes, their genuflecting replaced by fingers on the nozzle. Walls covered with patterned shards mingle trompe l'oeil tile arrangements, found in stone floors throughout the Mediterranean since 400 BCE, with the garish colors and flattened textures of vernacular signage.

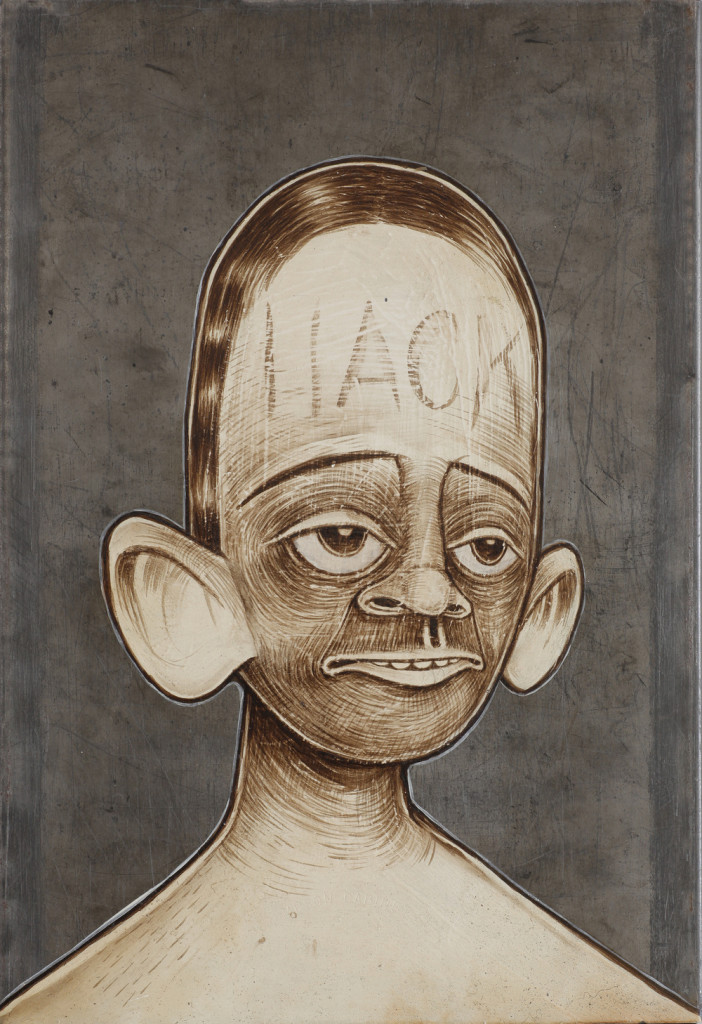

Barry McGee

Untitled, 1997

Housepaint on tin galley tray

13 1/2 x 9 1/4 in.

Collection of Jay Pidto and Lynne Baer, San Francisco

Photo: Wilfred J. Jones

A disturbing boil, oozing out into the room from the wall, carries with it a tidal wave of framed photographs and sketches. Accumulation is expressed as a growth, a mass, a tumor, which puts the institutional space under stress by suggesting an imminent eruption. But the inflation, repetition, and suggestion of collapse, which many may interpret as playful irreverence, can also intuitively be perceived as a manifestation of doubt—the wooden head banging against the wall, that has all the indications of being a self-portrait, doesn't help dispel the feeling of creative unease. The artist is conflicted and unresolved. He accepts his presence in the museum, yet shrouds the work, almost entirely made in the late 90s and early 00s, in an atmosphere of frustrated effort. He tags "HACK" across his forehead.

One could say all this is evidence of irony, self-deprecation, and that the joke is on us. The last room in the show is a local re-staging of a museum within the museum. McGee "curates" the work of local street artists alongside memorabilia from his life. Everything is encased in plexiglass boxes, offering up an ersatz of lived experience. It is eerie to see someone still relatively young struggle to relinquish hoarded bits of youth and drag others along with him in this premature preservation of what should be a dynamic, fluid practice.

Instead of perpetuating a conversation about the place of street art in the institution, I'd like to draw attention to this individual attempt at expressions of sorrow, loss, and what feels like self-loathing resulting from stagnation. At a crossroads, McGee could shed some of the aura of early underground stardom, to arrive at more complete sculptural expressions that do more than memorialize and re-enact lost youth. In other words, lance the boil, topple the TVs. Or, he could find a way to transform the practices that initially drew Twist* into the museum in the first place.

- Craig Costello Twist, 1993 Digital scan from silver gelatin negative Courtesy of the artist

- Barry McGee Untitled (Crawling Man), 1999/2012 House paint on tin galley trays mounted on plywood 77 1/4 x 68 x 132 in. Private Collection Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

- Barry McGee Untitled, 1998 Ink, graphite, acrylic, commercial screenprint, and photographs on paper, frames 115 x 280 1/2 in. Collection: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Miriam and Erwin Kelen Acquisition Fund for Drawings, 1998 Photo: Glenn Halvorson

- Barry McGee Untitled, 1997 Housepaint on tin galley tray 13 1/2 x 9 1/4 in. Collection of Jay Pidto and Lynne Baer, San Francisco Photo: Wilfred J. Jones

Barry McGee, which runs from April 6 through September 2, 2013, is organized by UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Its presentation at the ICA/Boston is coordinated by Jenelle Porter, Senior Curator.

www.icaboston.org

In 2004, Christophe Perez reviewed Barry McGee's show at the Rose Art Museum for Big Red & Shiny. You can read that article here.