Two current major exhibitions in Boston feature artists that can be regarded as outsiders: Kai Althoff at the ICA, Boston, and Barry McGee at the Rose Art Museum, Waltham. Although it is not obvious that Althoff and McGee can be lumped together, their shows display similarities that go way beyond both artists’ same age (38) and raise the question of relationship of a fringe of today’s art with folk art. Both Althoff and McGee are inveterate homies who still live and work in the city where they were born, respectively Cologne and San Francisco, and seem to enjoy nothing more than sedentarity and the daily company of their buddies (opposed to dinners in New York with major collectors). Both display more wariness than respect toward the art establishment, despite recent exposure at highly visible and publicized events. Both have a “double artistic life” and were primarily known for another art form, outside of the sphere of visual arts; tag and graffiti for McGee, music for Althoff. Last but not least, they both brought into the exhibition space almost everything that has composed their respective lives and eclectic activities for the past fifteen years.

Let’s begin with Barry McGee, to whom Rose Art Museum curator Raphaela Platow offered his first personal museum exhibition on the East coast. McGee is really the kind of artist who doesn’t feel right when in the white cube and who cultivates an ever-outsider and rebelious posture. Like a Basquiat who had never met Warhol nor heard about Gagosian, he practices most of his art in the streets of his hometown San Francisco, doing graffiti and tag under the pseudonym Twist and doesn’t taste much the social rites of the art world. The parallel with Basquiat stops here: despite his tagging background Basquiat did not consider himself a "graffiti artist"; McGee does. Even though he more and more often consents to crossing the line between underground and institutional, his strategy doesn’t vary much. Most of all, the show features various contraptions/constructions documenting McGee’s life backstage, from spray paint cans in many parts of the installation to a lifesize sculpture showing how three piled-up men can tag at fifteen feet over the ground on a pristine museum wall. Beside a few accumulations of the cartoonish framed small-scale drawings that are his trademark, come large-scale wall paintings, two of them featuring politically engaged caricatures of Bush and Cheney; others are made of politics-free though beautifully colored geometrical patterns. McGee also created site-specific and interconnected installations: a dumped and tagged van welcomes visitors in the museum yard. Inside, there are more of his sculptural junkyards including cars (or parts of cars, lights on) and VCRs working or not, most of them painted, many of which connected to aging TVs featuring video loops of tags and graffitis in the making, a scooter rider practicing wheelies, latino gangs in full representation mode... Among displays of so much punkiness, a curious oedipal counterpoint comes with a small edifice of rusty steel entirely covered inside with drawings on napkins by McGee’s father. It emphasizes above all the artist’s respect for the handmade and the recognition of alternative forms of self-expression.

At the ICA, Kai Althoff’s Kai Kein Repekt, the artist’s US museum debut, curated by Nicholas Baume, is an extensive survey of Althoff’s work to date. Among lots of drawings, the show includes a few ones made during Althoff’s childhood and teenage years. It also includes an exhaustive release of his disks, since Althoff’s eclectic band Workshop, that he created in 1990, constitutes a major part of his creative production. The entire show is embedded in a one-of-a-kind work that amazes from the first glance: Althoff repainted the entire exhibition space with spacially interconnected primary colors. This wall painting is in itself a masterpiece of border-line taste. Most of Althoff’s drawings (watercolors, collages, pen on paper...) and paintings are led by narratives referring to personal memories intermingled with imagined stories and even involving fictional collaborations. Althoff also quite often deals with religious subjects, copying existing art works, and acknowledges “being religious”. All these themes are addressed through a wide range of pictural styles, often reminiscent of, but not limited to, German expressionism. German folklore and popular imagery, especially from the ‘60s and ‘70s, as well as modernist abstraction are also convened. Along with music and picturality, Althoff’s artistic abilities encompass performance, poetry (released on photocopied letter paper sheets), installations (reminiscent of Beuys), ceramics and videos. In many ways, the installation involves the viewer in a “relational aesthetic” experience, inviting him to choose between selections of discs, videos, books and catalogs.

The “folk” issue: is it possible to be both in and out?

That Althoff and McGee don’t give a damn about genres, categories, market matters and the art world in general, is that enough to qualify them as outsiders or folk artists? The question resides on a hazardous terrain that every art critic should enter with much care. The word “folk” doesn’t sound good to many artistic ears since it evokes at first an art exempt of intelligence, awareness and/or premeditation. Regarding Althoff, the question seems prevalent enough to be immediately discarded by ICA curator Nicholas Baume in his introductory essay. After reminding us that Althoff is “largely self-taught, [...] attended art school interminttently without graduating” and that “[he]does not readily participate in the international art circuit”, he promptly declares: “At the same time, it would be mistaken to consider Althoff an outsider artist; his work is informed by a sophisticated understanding of visual culture and history, both “high” and “low”, and he has participated in an active artistic scene in Cologne for over fifteen years.”

Although it’s indeed not certain that artists such as Althoff or McGee should be called outsiders, they do participate in a wave of “new folk aesthetics”. The term was already advanced by Eungie Joo in May-June 2002 Flash Art’s issue in her article titled: The New Folk. Considering the specificity of the San Francisco art scene, including Barry McGee, she writes: “Here is a practice of social observation, expressing a deep engagement with craftsmanship, documentary record, and storytelling. While some have been careful to distinguish this work as respectful of yet distinct from folk art, it does emerge from a kind of folk practice. Process and scale are perhaps the most significant aspects defining this approach, manifested in a constant, almost obsesive production of both small and large scale works.” As a matter of fact, there are nowadays numerous examples of artists, not only in the San Francisco area, addressing art making with true folkitude mixed with various degrees of conceptual awareness, self-conscience and distance. Another common aspect is that these artists make everything that composes their art personally significant. The examples could even include to some extent Belgian-Mexican Francis Alys, who intensively collaborated with street sign painters in Mexico, or even British ceramist Grayson Perry, whose ceramics are now promoted as “high art” by the Saatchis. It is not even rare that the “art world” praises the work of less experienced or knowledgeable artists. Examples go from professional skateboarder Ed Templeton to highly depressed (and depressing) song writer Daniel Johnston. But are these ones really at the other end of the spectrum, and nowadays is there really such a thing as "high art" that stands above less informed art practices? Personally, I don’t think so.

Links:

Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

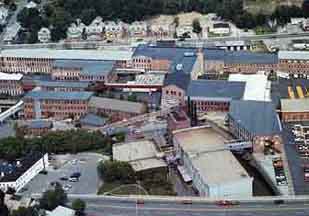

The Rose Art Museum, Waltham

"Kai Kein Respekt" is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, located at 955 Boylston St., Boston. "Barry McGee" is on view at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, on 415 South St.,Waltham.

All images are courtesy of the artists and of the ICA Boston and The Rose Art Museum.

Christophe Perez is an editor of Big, Red & Shiny.