Marcel Duchamp was always part of the market. Indeed, one can argue (and many have before me) that nearly all of Duchamp's gestures were linked in one way or another to the economic machinery of his time. His readymades (the shovel, the bottle rack, the urinal and the bicycle wheel) were dependent upon the signature of the artist, or the artist's perceived authorship, to call a utilitarian object into a different kind of being. The strategy to relocate an object from one category to another (durable good into collected artwork) wreaked havoc on modern art, and is still being negotiated today. In his excellent book "Imaginary Economics"Olav Velthuis mentions several lesser-known Duchamp works that speak quite powerfully to Duchamp's ongoing concessions with the market economy.

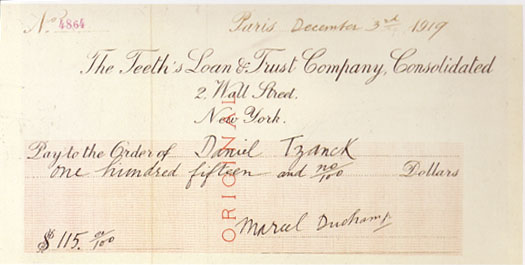

In 1919 Duchamp wrote a check to his dentist Daniel Tzanck in order to pay a bill. Now known as the Tzanck Check, Duchamp fashioned the details in the larger than normal check to resemble real currency as closely as he could. Olav Velthuis noted that Duchamp emphasized the amount of work he put into the minute details, even 50 years later: "I took a long time doing the little letters, to do something which would look printed- it wasn't a small check." Tzanck Check is remarkable in that it is almost a precise inverse in Duchamp's more famous tactics. While the readymades appear to be born of an almost effortless gesture, a simple signature scribbled on the side of a urinal, Tzanck Check was labored upon, rendered to appear as genuine as he possibly could. Also, Duchamp exported this check, his artwork, and received services for it, presumably an acceptable teeth cleaning.

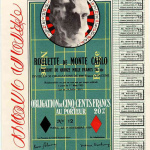

Five years later, Duchamp made the Monte Carlo Bonds, a financial certificate that he hoped would fund a roulette project of his own making by breaking the bank of Monte Carlo. It remains a bit hazy as to what exactly Duchamp had in mind for this project. Velthuis simply notes that Duchamp wished to "brush aside his chances and luck and, instead, to play roulette on the basis of reason and calculation." The Monte Carlo Bond was produced with the idea that investors in the project would receive an annual dividend of twenty percent. The obligation, which presumably satisfied participation in the project, fashioned itself, like theTzanck Check, from an actual financial document used at the time. At the top of the "bond" is a photograph by Man Ray of Duchamp with his face covered with shaving cream. The photograph, along with the roulette wheel framing his covered head, reads like a stamp of approval, while the betting table that makes the background of the document further accentuates the aura of official notoriety. The document is signed by Duchamp's alter ego Rrose Selavy, president, and by Marcel Duchamp, one of Selavy's secretaries. That nothing more came of this project should surprise no one, but is disappointing nonetheless.

Perhaps what most satisfies me about Duchamp is the confidence he always carried. To dream up such convoluted ways to make money is admirable, if only because no one else seemed to be making money in such a specific way, at least no one that was trying to launder it through the art world. I applaud Duchamp for his attempt to destroy Monte Carlo just as much as I love him for finding inventive ways to pay his dentist. Who else has tested the limits of art and economy as poetically as Duchamp? While neither of these projects garnered much attention (only 12 of the 30 bonds produced sold), both did receive something modest in return: a small amount of money and services rendered by a dentist. No matter what it was, it allowed Duchamp to continue doing what he wanted. This is economic poetry at its best: Modest, self-fulfilling, reciprocal and seemingly futile, yet always finding value in surprising ways.

- Marcel Duchamp, Monte Carlo Bonds, 1924.

- Marcel Duchamp, Tzanck Check, 1919.

All images via Google Image Search