In Real Art Ways' front room gallery, Zak Ove's group of photographs entitled Blue Devils (from the Transfigura series) greets viewers with a startling view of Trinidad Carnival. Large-scale photographs show men and women in gruesome masquerade known as the "Blue Devils," brightly painted in white and blue, feathered and bloodied. Traces of African tribal memory mash up with European Catholic festival tradition as the players perform this escapist rite of passage. Through Ove''s lens, the scenes look terrifying, exhilarating, radiant and menacing. Ove documents the annual pageantry with a particular interest in those who year after year take on their fanatically developed characters and march in the now world-famous expositions of Caribbean religious and cultural heritage. The work is equal parts dramatic documentary, historical deconstruction, decisive portrait-making and spirited participation. As a London-based artist of Trinidadian descent, Ove's devout fascination for the subject matter is reflexive, representing a personal journey.

As a singular component to this larger effort, Ove's work is a powerful introduction to Real Art Ways' ambitious exhibition, Rockstone and Bootheel: Contemporary West Indian Art. The show brings together the work of 39 artists from the Anglophone West Indies and its diaspora. That is, the Bahamas, Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago and abroad. "Rockstone and Bootheel" is a Jamaican colloquial expression which means "taking a journey," lifted from a dub-metal song by Gibby. The show gathers a variety of racial and political contradictions, surveying the many creative practices of artists coping with and/or enjoying island life and its tumultuous, ongoing history.

Jamaican artist O'Neil Lawrence shows three exquisite photographs of male nudes walking into a tranquil beach's tropical surf. Formally, Lawrence's photographs are classically beautiful for their color, composition and sensuality. Bodies partially covered in white cloth and clay, allusions to baptism, rebirth and re-identification are made. They picture a hesitant yet willful return to the ocean, a haunting reminder of the middle passage, of forced immigration and slavery. Elsewhere in the show, similar imagery appears in video artist Annalee Davis's documentary, On The Map, about Barbados' devastating immigration policy.

Blue Curry, a London-based artist born in Nassau, presents an untitled sculpture- a creamy pink conch shell with a flashing strobe light embedded within, which excitedly lights up the surrounding area. It is a clear-minded, one-two punch with succinct metaphorical significance. The shell sits as a symbol of exoticism, tourism and imperial export, emanating an inner magic and entrancing its beholder. Here we understand the West's obsession with Caribbean music and club culture, its beaches, and the unflinching desire to colonize them.

The Jamaican born, US-based artist Lawrence Graham-Brown's sculpture Ras-Pan-Afro-Homo Sapien confronts challenges to Jamaican gay and black identity, presenting a mannequin torso dressed in a brightly colored military jacket. The proud, broad chest bears the likenesses of Rastafarian, black power, gay rights and pop music icons on dozens of rudeboy badges. A sash of Jamaican currency runs diagonally across the shirtfront while a plume of feathers attached to the back recalls those of a peacockish dancehall diva. A small Jamaican flag is tucked into the front pocket like a flamboyantly political pocket square. A silk rose and a bundle of sticks (a literal faggot) are crowded into the same pocket, signifying an uncomfortable yet confident fusion of personal and political identities. It is this show's stand out.

There are too many stand-outs to describe, however. But if I can, Renee Cox's anxious but amusing photographs of dress-up self-portraiture remind me of Cindy Sherman, with less Hollywood winsome.

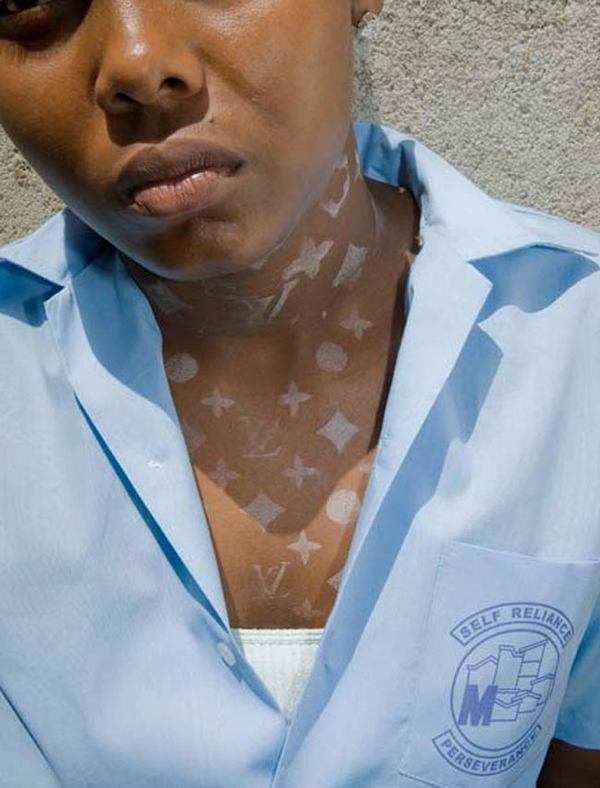

Ebony G. Patterson's Gangstas for Life explores skin bleaching beauty trends among urban male youth. Her large portraits are iconographic, corroded, affecting and fabulous. Satch Hoyt's Rimshot is an altarpiece for the universal ghetto. It combines wall-sized rosary bling formed out of showy custom wheel rims with a bumping bass rhythm that fills the gallery like the voice of God. It is a sharp material commentary.

The Caribbean's geopolitical position in relation to the rest of the Americas, Africa and Europe is peculiar, even special. Knowingly, many of these artists are involved in savvy creole disruptions of the dominant racist, misogynist, homophobic, imperialist West (that is, the very world powers which brought them to this painful uniqueness). They engage in identity bricolage not as a means of desperate, hegemonic survival so much as a strategy for successful artistry and worldly self-awareness. Real Art Ways' informed presentation pays due attention and appreciation to this area of the world whose cultural impact has been felt globally, yet vastly under-recognized for decades.

- Marion Griffith, from the “Powder Box Schoolgirl” series

- Ebony G. Patterson, Endz (Khani + di krew) (detail)

- Christopher Cozier, Sound System, sound performance

"Rockstone and Bootheel: Contemporary West Indian Art" is curated by Kristina Newman-Scott and Yona Backer, on view November 14, 1009 - March 14, 2010 at Real Art Ways, 56 Arbor St., Hartford, CT. The 39 participating artists are Akuzuru, Ewan Atkinson, Lawrence Graham-Brown, Renee Cox, Christopher Cozier, Blue Curry, Sonya Clark, Makandal Dada, Annalee Davis, Khalil Deane, Zachary Fabri, Joscelyn Gardner, Marlon Griffith, Satch Hoyt, Christopher Irons, Leasho Johnson, Ras Kassa, Jayson Keeling, O'Neil Lawrence, Christina Leslie, Simone Leigh, Jaime Lee Loy, Dave McKenzie, Wendell McShine, Petrona Morrison, Karyn Olivier, Zak Ove, Ebony G. Patterson, Omari Ra, Peter Dean Rickards, Nadine Robinson, Sheena Rose, Oneika Russell, Heino Schmid, Phillip Thomas, Adele Todd, Nari Ward, Jay Will and Dave Williams.

All images are courtesy of the artists and Real Art Ways.