David Kramer is a New York artist who has exhibited in Toronto for the last fourteen years. I interviewed David via email at the close of his recent exhibition at Birch Libralato.

Jennifer McMackon: David Kramer, one of the last times we spoke, you used the word oligarchy ! Its not that common a word in casual parlance. Do you remember when you first heard that word? In school?

David Kramer: A few months ago I was talking to this guy I know. He is this union electrician, a totally blue collar guy. So we are talking about politics and that can always be this touchy subject in The States. But he starts railing on George Bush and the lies and veneers that he and his people dish out.…everything from the bullshit about the “Axis of Evil” to “Every American Should Own a Home”.… Anyway we arrived at this idea that this administration had done this fantastic job of spewing good and evil and playing them against each other while making guys like him, and me, poorer and poorer and more in debt so that the chosen few could have their run with things. This guy had worked in The World Trade Center and had friends who had died there. And for people like he and I, invading Iraq never made any sense and never would have even been on the table. The oligarchy thing has been at the tip of my tongue ever since.

JM: Did you go to art school? Where did you get your formal art training?

DK: I had a very weird art education. I went to school in Washington D.C. during the Reagan years. I was thinking about going to law school and majoring in economics. I got a job in the White House Mail Room. But I began to realize I was in the wrong place when my class mates re-elected Reagan in a campus poll. Anyway, in my junior year I got back to school after break and got my grades. I had gotten a D in accounting. I had worked my ass off but I was a terrible test taker. I spoke to my accounting professor who explained that there were only x amounts of A's, B's and C's, etc per semester and that my grades put me squarely in the D's. I said that I had worked my ass off and deserved some credit for my hard work and bad test taking skills. Well, my teacher said that accounting was not a subjective field of study. So I dropped my classes in Business and transferred to the Art Department. It took me years to realize that Art is not really a subjective field either. If I couldn't talk my stupid accounting professor out of getting a D, how was I going to convince anyone of my ridiculous art ideas when in the Art World it hardly matters what you put on a piece of paper when it comes to how it is measured by critics. In some ways I am still gettting formally educated all the time.

JM: Did they have any oligarchs in the Art Department?

DK: My drawing teacher also gave me a D. I am dyslexic. We had to memorize all the bones and muscles in our anatomy . My spelling was awful and even though I could draw better than anyone in the class, he said “There are people in this class who don't even speak English that can spell better than you!” Maybe he wasn't an oligarch, but he certainly had fun with his shitty little amount of power.

JM: How is it that you chose art school? In retrospect, were you always a creative type?

DK: When I realized that I wanted to be an artist, I knew that I was in the wrong place. I wanted to get an MFA and learn something. I wanted to “catch up”. I applied right away to a number of schools and the only one I got into was Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. So I moved back to NY where I am from. My parents were devastated. They had been raised in Brooklyn and spent their entire lives trying to get away from there. I was going to throw it all away and go back. But I figured that if I was going to have to spend all of my time doing something, I should spend that time doing something I like...even if it didn’t pay all that well..

JM: You and I met in 1993. At that time you presented pretty much as a sculptor/ language/ installation artist but shortly after that your work took on a more pictorial emphasis. You made a really bold move into painting which persists in your work today. I remember seeing some of your paintings for the first time in your old studio. Quite aside from the imagery or your painting skills or anything else like that, I remember being amazed at how heavy and overbuilt your stretchers were. They were um, fortified. What are your thoughts about that time, that transition?

DK: I made really good stretchers back then. I still over kill the stretcher bars when I am putting together a canvas. I guess I spend a lot of time working on things that nobody will ever see - lots of covering up as I move forward - the story of my life really. But I remember back then what I was painting: body builders and bikini models. In some ways I am doing the same paintings now, only I am writing on them too....I think that my jokes are better these days than they were back then. And I sometimes know what I am doing with the paint.

JM: What kind of typewriter do you use to imprint the texts on your drawings? Where did you get it? How long have you had it - or has there been more than one typewriter in your life?

DK: Years ago (1986) I moved into an apartment and there was this old Smith-Corona typewriter in the room that I rented. I have been using it ever since. I definitely think that it was one of the best "finds" in my life. I love typing on a manual and I grew up with them. But when I was using them in school, they just came along with the baggage of how bad of a speller I was.Now it is kind of liberating. I definitely write differently depending on what I am using.

JM: I ask about the typewriter because it imbues your text drawings with intermingling qualities. It lends a percussive, tactility to your narratives. More than a few times looking at your drawings, I've had the sense I could hear them being tapped out of the machine as I read them. And then there's this funny dichotomy between their deriving from someone's journal, your private diary and yet somehow reading fully pants down in public, hot off the press. Are you a diaristic exhibitionist?

D. K.: When I first started to work with a typewriter, I was kind of making concrete poetry or just writing one or two thoughts. I had a couple of friends who were writers and they encouraged me to read my stories and "poems" out loud. I had bad stage fright issues. but I did it anyway . I mean, nobody else was asking me to do much of anything with my work in New York back then, so what was I going to do, say "no!"? So I started to perform and I really think that it changed my writing forever. For a while, like four to six years ago, I was performing the stories a lot. I had some friends in the theater and would read them at this variety show. I was still nervous every time I read the stories and I would link them together with these anecdotes to somehow frame where the story was coming from. I don’t know whether it was my shaky delivery mixed with abject fear or the content of the stories themselves, but the people in the audience always wound up on the floor laughing. Now the drawings really feel like something of a performance piece on paper to me.

JM: In his Globe and Mail review of your show at Birch Libralato, critic Gary Michael Dault remarked your work seems to".... to dote upon irony and mordant defection -- even to the point of taking refuge in it. " How do you respond to that?

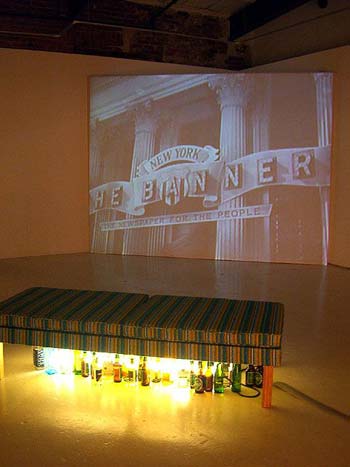

DK: Gary Michael Dault chose to ignore my video Million Dollar Moment which I think really sums up how he saw my work in the first place. I made this video in which I shoehorned a real life story of how I got my break with Feigen Contemporary with all of the mythology I attached to the way of the art world as spooned to me by Ayn Rand. The video steps on the toes of art critics because it claims that they have all the power and the critics come off (as in Fountainhead) as gross and unfair oligarchs. In Ayn Rand, the artist (architect) is the hero. In my version, the artist is a lazy boob. But the critic can't stop this boob from getting his break anyway. It was broad and artworld noir. But it was supposed to be funny. I made it because I was shocked that I had worked so hard my entire adult life, and it took a case of mistaken identity for me to ever get a break...it IS irony.

As a critic he might have felt like I was stepping on his toes because of the movie. Or that I am glib or a smart ass. But my motivation to make it was pure joy and surprise at how things in my life had turned out. Some things you can definitely put blame on or point a finger at, but mostly life is much too complicated. That is why I am drawn to absolutisms like "The American Dream" or "The Protestant Work Ethic" or "The Hollywood Ending." I am truly confused why I know that these things are mostly false hopes. But I keep on believing in them and living my life in chronic disappointment. I keep myself from getting depressed by laughing at my gullibility.

JM: Do you think the stirring of empathy is an underrated thing that art can do?

DK: I think a lot of what I write about is done for my own catharsis. I am amazed that people can relate, to be honest. But in the end I want people to laugh and be entertained by my stories. I don't mind being the boob if it gets a few laughs. I don't want anybody to feel sorry for me or sad. But getting people to relate, that is what I think good art is all about. Sometimes I stop dead in my tracks and take a long look at a piece of artwork. This is out of empathy I think. And the piece can be fucking abstract and still get me to feel that way. I certainly try not to be so direct in my art making. But I always hope that people can relate. Otherwise what are they looking at it for...?

JM: I find that last remark to be critical, actually crucial. And I think Million Dollar Moment is a critical piece in your work. The last time we spoke you made a point of correcting me, saying that the piece is not critical but rather satirical. Do we understand the term critical the same way? Do you think artists and critics understand the term the same way?

DK: Critics, they pass judgment. They get paid to be the gatekeepers who decide what is good or bad. They are powerful. More people read newspapers and websites than ever make it to the gallery. And critics, they abuse their power all the time. They don’t review one person’s work because they don’t like them or they don’t go see some show because it’s raining or cold or whatever. And then they can make or destroy careers without really paying attention. I saw one writer here in New York for the Times write a review of this one artist who she says is stuck in his ways. He keeps making the same work over and over again.… Then in the same month she writes about this other artist who she showers with praise for sticking to his guns - not letting outside influence change his work. We live in this Age of Pluralism, and yet the same five or six people write for the Times every week. And they’ve already decided whom they like and don’t like. As far as artists go , artists always want to see their names in the paper. We love to be written about. We hang on every word. It validates what we are doing. I have never gotten much press in New York. And I have, as a result made more and more work that is satirical of the system. I like to talk about the absurdity of the art world and of the role of critics. It is compelling stuff to me.

JM: How many times have you shown Million Dollar Moment? What has been the overall critical response? Is it different away from at home?

DK: I showed Million Dollar Moment at Feigen Contemporary in 2004 and with Birch Libralato in 2006. That’s really been it. In New York, every critic from Michael Kimmelman on down came to see the show. The only person to ever write about it was Kim Levin for the Village Voice. She loved it but everybody in New York says she is crazy.

JM: One thing I appreciate about Million Dollar Moment is that your typewriter seems to have orchestrated something more than a narrative tidbit - actually a screenplay. And your camera nabbed the look of a faded silver screen of days gone by. To this you added homespun acting talents and hilarious cameo appearances. Can you talk a little bit more about acting and performing. We've seen it increasingly in your work but Million Dollar Moment is cinematic - theatrical. Where did that come from?

DK: As far as the look of the Million Dollar Moment, I wanted to make an old Hollywood style film in the look of the film version of the Fountainhead.

It is a flawed film for sure but always one of my favorites. I have been making more and more narrative videos since 2002. I had this gas explosion in my studio and over half of everything I ever made was destroyed. It was at a moment in time that I really have to admit I was wondering if maybe things would never work out for me being an artist. Anyway then this gas explosion happens and I am sitting here thinking that maybe it is a sign from God that I should get out of this business. But at the same time, I literally just left the building to get my lunch and by the time I got back, all the walls were gone and the fire trucks were dousing the flames. I dodged the bullet really.

Anyway, this motivated me and I made this short video called Asshole 2002. My wife is doing laundry in the basement of my building describing to the camera what a lazy shit I am, and here we go again with the lame-o excuses for why I can’t get my shit together. This is all juxtaposed with me sitting with my thumb up my ass in my new studio doing nothing while text streams across the screen using the most potent September 11 jingoist statements (the explosion happened a month or so later) about what a horrible, sad tragedy just happened to David Kramer and his studio. All of this to the soundtrack of Schindler’s List. Anyway, this was when I really got the sense of how to exploit my stories for film effects. I mean, it was another cathartic exercise (personal tragedy had little place for Americans that Fall if it didn’t have to do with September 11th). But I was driven to make it entertaining. I also wanted to say something about personal tragedy at a time when all this country could talk about was finding somebody to get even with. I didn’t want this gas explosion to get the best of me, either.

JM: There is a scene where your Ellesworth Tooey character is pontificating in front of the Guggenheim Museum when a fellow who looks just like you saunters through the background. Is that you or my imagination?

DK: I am not doing my Alfred Hitchcock at that moment. But it would have been funny.

JM: . What living artist has most influenced your work?

DK: That is a hard question. I am most touched by work of artists from the West Coast. Like Ed Ruscha , Rodney Graham and Jim Shaw. And yet I always feel like all the West Coast artists whose work touches me have a sort of cool or WASPy sensibility. I sort of start out trying to make cool art but it always seems to get all fucked up with my East Coast Jewish Angst. Maybe Roy Lichtenstein...but he's dead already.

JM: What is your favorite work in all of art history?

DK: Vincent Van Gogh's self portrait with the blue hat and bandage.

JM: Ha! Is there an artist you would like to meet if you could be transported backward in time?

DK: Philip Guston.

JM: Have you ever had really good art envy? Have you ever seen a work of art by another artist you wish you made yourself?

DK: David Smith's Hudson River Landscape.

JM: What are you working on right now and when will we get to see it?

DK: I have an idea for this new video project. It is at the very beginning but its about my relationship with this particular art critic guy who knows who I am and says all kinds of things about me to other people but pretends that I don't exist or that he is invisible when we've crossed paths at parties or openings or even on elevators .The whole experience, which repeats itself often, reminds me of Junior High School. But I haven't even written a script yet.

JM: How many tuna fish sandwiches do you estimate you have eaten in your life?

DK: Too many to count at this point.

Links:

Birch Libralato

"David Kramer: Objectify My Life So As To Give It Meaning" was on view November 25 – December 23, 2006 at Birch Libralato.

All images are courtesy of the artist.