Art in Service: a conversation between Leah Triplett Harrington of BR&S, Kate Gilbert of Now + There, and Maggie Cavallo of Alter Projects

Last month, the City of Boston launched Boston Creates, its first-ever cultural plan. The ten-year plan aspires to enable all of its citizens to “participate and take pride in the vibrant cultural life to be found in every corner of the city.” Simultaneously, the City is beginning its second round of Boston AIR projects, putting socially-engaged artists in residency with government offices and agencies.

As citizens engaged in contemporary art practices in Boston, how do we understand the network of artists currently working in socially-engaged practices? How can we (or do we need to) assess and optimize access to the medium? Is it our task to build a field and lexicon for artists and audiences, or do these practices rise above the requirements of such definitions? What traditions do these artists and projects emerge from and how can we, as writers, practitioners, and artists, critically engage with art that seeks to serve a community from which it evolves?

Over the course of the next several months, we will be discussing and writing about these projects and issues through Art in Service, a four-part series co-produced by BR&S and N+T with contributing writers Maggie Cavallo, Leah Triplett Harrington, Kate Gilbert, and other local artists. In the conversation below, we let a broad view of the topics we’ll discuss in this series unfold, including projects happening this summer, attempts at defining socially-engaged art and proposing what the qualities of participation in art can, or should, look like. Our goal is to contextualize our thinking about socially-engaged globally, nationally and site-specifically to Boston where our own precedents and critical histories offer a unique and valuable approach to such practices.

Maggie Cavallo: Our initiative here is dedicated to 'field-building'—pinning down language, describing methods, identifying practitioners and resources. But these practices (of socially-engaged art) are transdisciplinary, sometimes but not always 'centered' within the field of contemporary art (see: art world, art industry, art institutions). What do we think about this?

Leah Triplett Harrington: I love your use of the words “field” and “trans” here. A field is an open plane in space, but it’s also a specific discipline or practice. It’s both open and closed. And trans: that’s a word we use to describe something that’s either/or, or transcends. So both terms have multiple means, and in some ways, can mean the opposite. I bring this up because it’s interesting that we use them when we are talking about socially engaged practice or approaches that are specific or centered in any one discipline. I think that’s a good thing, but I also think that makes it inherently awkward/cumbersome to write about, or for audiences to grasp immediately.

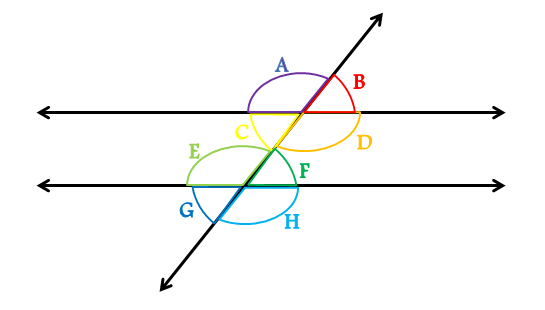

MC: I’ve been looking more closely at etymology, I want to get to the roots of what the words we’re using mean. In Art, Design & Learning in Public at Harvard Graduate School of Education, Professor Steve Seidel and I dedicated a portion of the class to comparing the terms: multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary. The goal was not to designate a hierarchy of practices but to know what these words mean and use the right one when describing artists or art works. Students wrestled around the terms, the way they describe how an artist will incorporate various media, including dialogue, institutional work, and other performative practices into their work. Multi suggests quantity over method, inter is among or between, trans is across, beyond or through etc. As part of the dialogue, students were asked to illustrate each word. I prompted them to do this after my own experience of being introduced to the phrase transversal as a way to describe an artistic practice. I looked up transversal angles and this simple geometry gave me a lot of insight. My own practice (the transversal line) moves through multiple sites (fields etc) simultaneously, each corresponding angle another related but separate facet of my work.

Kate Gilbert: Part of what makes socially engaged work (SEA) difficult to define, discuss and evaluate stems from the fact that it’s a rapidly emerging field with various terminologies. For the sake of this discussion SEA is appropriate but let us not also forget it’s older nomenclature: participatory public art, new genre public art, social practice (leaving out the word art), and social sculpture (credited to Joseph Beuys). One participant once responded to a project saying, “Well, it seems like a happening. I’m not sure what the goal is, but it’s fun!” which reminds me of the Fluxus movement.

Another reason it gets cumbersome to write about, and why I believe we slip into art-speak, is because each project has a different agenda (e.g., giving voice, being antagonistic, providing joy). How can we call it art when the work is awkwardly similar to the practice of a trained therapist or seasoned activist?

MC: Yes, it’s critical we understand the various histories of this work along with their languages. Before we ‘named’ it (relational aesthetics, new genre public art, social practice etc), how were such practices understood? Who were the community leaders, healers, and educators whose practices are the roots for what we are describing through a lens of art?

This is a crux for me, so what about the relationship between socially-engaged practices and the field of contemporary art? Where do we ‘center’ this type of work? Why go through the process of defining such practices is their elusive nature is often what makes them the most viable or effective? I remember feeling such camaraderie with Rick Lowe in his interview with Tom Finkelpearl, he describes how the closer he got to working in ‘the community’ (joining social justice organizations etc.), the less his art friends were able to relate or connect with him, he felt the space between them grow wider. At the same time, lenses of art—place, site-specificity, time, craft etc.—are often the exact tools that help us translate, design and execute quality work outside of the ‘art world’ setting.

I’m curious to talk more about how defining SEA fits into a history specific to Boston, its history, and present. I think the Brahmins were pretty crafty socially-engaged cultural producers, but they did so to define and contain art away from the ‘public’. Today, the role of our Educational institutions, a sharp and self-aware youth community and general emphasis on social justice also presents its own unique atmosphere of socially-engaged practices.

LTH: I think this question will be approached through this series, but to answer it on its most essential terms, I would say that for me, experiences of this type of work always comes back to gesture. (Which is something that Deborah Fisher of A Blade of Grass spoke very intelligently about when she was here screening Fieldworks). Gesture connects this practice to painting--specifically action painting--and it also literally speaks to the inherent aspect of the work, which is to effect social change, or to move people or institutions.

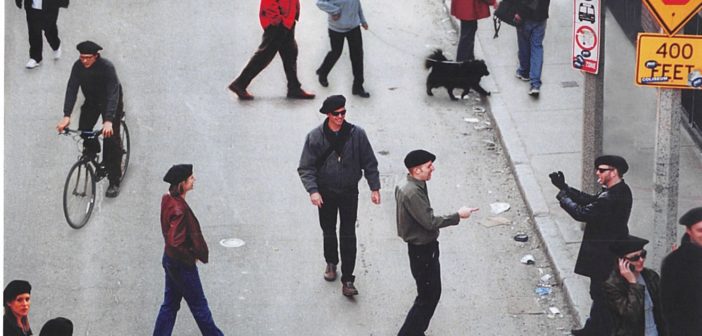

KG: My go-to definition of SEA is Tom Finkelpearl’s, “art that’s socially engaged, where the social interaction is at some level the art.” from ArtNews (April 7, 2014) and his book What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation. Boston has a long history of doing this type of work but as Maggie suggests, it wasn’t centered in the art world. It couldn’t be, there was no market for it, no way to purchase or resell it. The work of the Revolving Museum, Mobius, and the Fort Point Arts Community in the late 90s to fight eviction was SEA. For instance, Jeff Smith invited anyone who identified as an artist to take one of hundreds of black berets and wear them for a week to make visible the number of artists who lived and worked in the neighborhood. The culminating event was a protest on A Street that stopped traffic and truck access to the region’s busiest post office. Today, Smith is using sculpture to take a stand against outrageous housing prices. While he’s not engaging the public in person with “The Smallest House in the World”, a rentable mobile home on AirBnB, the work has been written about all over the world, including five times in Russia. I’m curious about the conversations this work is prompting. Do we always need to experience a project to get it?

Jeff Smith's Smallest House in the World.

LTH: I love Jeff Smith’s Beret Day project! I’ve done tons of research into contemporary art practices in Boston in the 1980s-1990s and only learned about it this spring through looking at the No Art /No Point project. No Art / No Point is documented in the New York Times, but I’ve never seen records in the Globe (for example). How should these projects be archived and accessible? This is something I hope to discuss more fully, later in the summer...

MC: I love this Beret project, was not familiar with it at all! This is the kind of story that makes me feel like I fit into some sort of regional art history here, a contemporary art history. It would be so useful to have a resource where these articles and stories were contained - something that helps contextualize this work regionally.

Kate, you mentioned the market (or lack thereof) then and now. I am at once eager and totally turned off by containing SEA practices and want to understand nuances of the ‘rapid’ nature of this ‘emerging field’ and evolving markets for such practices which I am actively (if not always comfortably) pursuing. I want to be able to describe how this parallels our language of ‘creative-economy’, ‘innovation’ etc.

Again, it’s likely important to look at the roots of SEA and their relationship to the economy of art and capitalism in general. On one hand, I know this work operates best outside of the industry of art. On the other, for me, various stratospheres of the ‘art world’ have become the actual site of my own socially-engaged practice. This all leads to a bigger question - where does socially-engaged art take place? How does our use of the word ‘social’ compare to our more common use of the word ‘public’—what difference does this make?

LTH: Really, really good question...again, I hope that this idea of where socially engaged art takes place, and the layers of meaning of the familiar terms ‘social’ and ‘public,’ becomes elemental in our series this summer.

KG: Great question! I’m currently reading up on Paul Ramirez Jonas’ theories on publics. The concept for Public Trust derives from Michael Warner’s book Publics and Counterpublics, in which Warner exposes the fiction of a “general public” sharing a unified voice. Ramirez Jonas suggests that new definitions of publics can be made by the “transient participants in common spaces,” those of us who’ll create and witness promise-making during the 21 days of the project. The project culminates in a book—that last step in a consistent process of transcribing, typesetting, and making promises—and that is where he believes a public is formed.

From Andi Sutton and Jane D. Marsching's Plotform. Via plotformplot.org.

But to me, I think ‘social’ seems more humble than ‘public’. Perhaps more quantitative. It can incorporate a small group knitting such as the collective work of Jane Marsching and Andi Sutton in Plotform, or an artist translating emotions into visuals such as William Chamber’s Service Station and Chanel Thervil’s Emergence: What does hope look like at the Boston Center for the Arts. To me ,the shift from public to social is akin to the movement away from big aspirational civic planning “for the public” towards hyper-local, grassroots movements that focus on solving the problem on our front stoops, and in our immediate social spheres.

MC: Off the top of my head I guess I see ‘public’ as a site that is often used to describe where or for whom art happens, social describes a different where and maybe the how with the acknowledgment that a discussion of audience/student/participant is a whole other story. There is no ‘public’, nor ‘community’—there are publics and communities. That said, I think socially-engaged art and comparable practices can/do play a role on large scale civic projects. Socially-engaged art depends on relationships, and the activation of relationships along with other content, intellect, and sites in service to something—maybe a specific, quantifiable goal, maybe something more ambiguous. It would be good to review the Boston AIR projects with these questions in mind.

MC: I’m further interested to discuss how artists balance collaboration and transparency with antagonism and subversion. Many of us use a critical voice and less-than-equitable procedures to make a statement, to cause confusion or discomfort along with creating pieces that are positive, democratic, solutions-oriented. As a society, I think we like to say artists are allowed to ‘start trouble’ but in practice, an artist who is vocal or critical is also risking the longevity of their ‘likeable’ personality to be antagonistic—are you awarded fewer grants if you are a trouble starter?

LTH: Subversion or antagonism could be a way for SEA to avoid “plop art” syndrome...

MC: The dialogue I hosted for re: development had me thinking a lot about antagonism. I was performing curator and moderator, I am actually both of those things but I was also consciously designing a discourse amongst urban developers, artists, and architects where I knew topics could (and need to?) cause tension, anger, misunderstanding. Learning happens in moments of discomfort. In retrospect I realized I needed the antagonism as an energy to drive the project, but when I actually designed the discourse it became a lot more nuanced. My questions were direct and specific, but equitable. They did not target any player as ‘bad guy’ or ‘savior’.

I have a similar feeling about teaching at the MFA. In the contemporary galleries, with small groups, we explore issues of identity that are offered up by many of these works, primarily race and gender. I acknowledge that I have to make space for my often white, cis-gendered audience to feel the discomfort of their own biases but it always has to be designed with a certain amount of grace so that they stick around and see the experience through.

There’s a lot more to cover here, and I’d like to get back into this in our writing later but the more I connect with Cedric Douglas the more aligned I see we are in terms of practice and questions of antagonism. He has made a name with a likable, well-designed and funded project (UpTruck!); the project's’ roots earnestly evolving both from graffiti and community organizing. But as an artist, if he wants to design a more critical, less likable project or exhibition, what is the risk to UpTruck? John Hulsey’s work with City Life/Vida Urbana, specifically “Letters to Bank of America” also comes to mind as a great example of shared ownership, solutions-oriented design processes and antagonism. Urbano Project offers opportunities for their artists to experiment with different levels of antagonism depending on the teaching artist. There is a larger conversation here of how this question of antagonism also relates to activism. I also think of when Nabeela Vega performs Visiting Thahab there can be an antagonism in just being, it evolves out of an Islamophobic social climate alongside/regardless of the how antagonistic they might actually feel about it.

Nabeela Vega's Visiting Thahab. Via nabeelavega.org,

KG: Agreed. When Visiting Thahab came to the Lawn on D their “just being” made more of a statement than the actual content of the performance may have. In that carefully constructed heteronormal space, gold-draped Thahab presented an antagonistic presence to the beer-drinking norm and disrupted the usual use of the park.

This brings up the question of audience and intent, as in, performance-based participatory works as acts to be received by the public versus platforms for engagement where the artist’s hand is barely seen. When evaluating a work I always ask who is the work for, and what is their role in it? Who is it serving? The artist’s practice? The community it’s engaging? Both? There’s a wide spectrum of practices out there.

MC: Yeah, it is critical that artists are able to consider the types of participation they are designing as well as who/how the work operates for. The new reader “Future Publics (The Rest Can and Should Be Done by the People)” says it all in the title, in terms of ‘ownership’. This book has been a huge help to me, that said, I want to talk about how artists use various participatory structures as media, I don’t think it necessarily can or should be ‘democratic’ in all works of socially-engaged art.

LTH: Is participation necessarily a media?

MC: I guess it depends on if the artist considers the design or craft of participation an element of the work. If they don’t, I’d have a hard time thinking much of it as socially-engaged art to begin with.

LTH: How can we appropriately document processual projects like Silvia López Chavez and Elisa Hamilton’s Lemonade Stand or Chamber’s Service Station? Both projects engage a variety of audiences through a variety of actions. How should critics or historians approach this type of work...if we can’t experience each part of the project, should we avoid writing about it? How can we responsibly write about this work, be it documentation or critique?

KG: This comes full circle back to No Art / No Point. Project catalogues are necessarily biased. That one was written by the producers as, I think, a requirement for the funder(s). But at least it was written by people who engaged with the work. Responsible documentation or critique of a particular project requires engagement on the part of the writer; a critique of the field or an artist’s pedagogy can be dissected from afar. Video seems to be an effective tool for bypassing the writer’s partial review and broadening the audience. Videos level the playing field, foreground the artist’s words and visuals, and allow the viewer to make their own assessment of the project. See FieldWorks: Season One by Blade of Grass for some terrific examples.

Paul Ramirez Jonas' Public Trust rehearsal at Grand Central Art Center, Santa Ana, CA 2016.

But video production must also be scrutinized. We’re choosing a videographer now and asking ourselves if we want a slick, upbeat video to match the nation’s 60-second attention span (e.g, tell as many people as possible know this thing happened and build broad awareness), or develop an in-depth documentary (e.g, give those in the field deeper access). Our solution is to do both, create an in-depth look at the project in book form and distribute the pleasing highlights-reel video. Obviously, not every artist can afford this kind of documentation and that pains me. Wouldn’t it be great if there were some filmmakers dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of past and future socially engaged projects?

MC: This is a huge question and one I’m excited to delve deep into. I would start off by asking, what is the purpose of documentation? How is that media used and for who? This has been one of the most significant benefits of pursuing research on socially-engaged art practices within a lens of learning at HGSE. On that campus, documentation is a tool used to catalyze deeper learning (e.g. the methods that can be found in studying Reggio Emilia). I think this view of documentation may also lead us to ideas of how we assess or critique socially-engaged practices.

From a journalistic standpoint, it’s tough because someone needs to be embedded in the process. You can’t write about a performative or socially-engaged project after the fact. Journalists in the arts in general need to be more embedded, this requires a durational reporting process which I know is not easy to fund.

LTH: There are a number of projects happening this summer that will encourage and stimulate many of the questions we’ve approached here. In August, look for posts on Now + There on participation and projects focused therein by Kate, and on critique and assessment from Maggie. I’ll be looking at a history of socially engaged projects in the BR&S archives and writing about Public Trust in September. Get in touch with us with #ArtinService

William Chambers's Service Station. Via william-chambers.com.

3 Comments

This is great. I have so much reading to do from this piece. Looking forward to more.

Glad to hear it, Bonnie!

Pingback: Big Red & Shiny -- Boston's Independent Online Contemporary Visual Arts Magazine: Reviews, Essays and Interviews about Painting, Performance Art, Photography, Sculpture and more