In college, she studied painting. She had wanted to be a writer. Her father was a writer. But in college, she transitioned from drawing fictions on a page to painting pictures onto canvases. She was committed to painting when she took a 3D course. She labored over soapstone sculptures, carving away at the surface. “You’re more of an additive than a subtractive,” her professor said.

She is Kate Gilbert, who, after twenty years in Boston, has ricocheted through every facet of the art community here. Currently a curator and director of Now and There, the public art non-profit who brought JR’s Inside Out Project to Boston last fall, Gilbert is an artist whose studio practice includes video, installation, performance, sculpture, and persistently, painting. Her practice and curatorial work are united in Gilbert’s enduring appreciation and fascination with art’s power when placed in public. While Gilbert’s curatorial projects, including WonderLand at the D Street ArtLAB and Faces of Dudley, boisterously convert open, “empty” spaces into shared, communal civic spaces, much her work as an artist focuses on the fragility of the private within the public sphere. Her practice dialogues with global narratives of power structures in its response to shifts in the Boston urban environment over the last two decades. Idealistic but decidedly more realistic than utopian, Gilbert’s work quietly dissents, augmenting and offering alternatives to the familiar.

Home—as a shelter, a center, a place of origin—is a persistent theme for Gilbert. She spent her early childhood in Hamden, a suburb of New Haven, which was also home to James Wines’s Ghost Parking Lot. Installed in 1978 within an indistinct shopping plaza parking lot, Ghost Parking Lot entombed junked cars from the 1960s and 1970s in pounds of dense, lava-like asphalt.

James Wines, Ghost Parking Lot, Hamden, CT, 1978. Via archdaily.com

The work is now gone (it was removed in 2003 after a twenty-five-year run), but as a kid, it was part of Gilbert’s every day, as her family shopped for groceries in the Ghost Parking Lot plaza. Gilbert’s father was a reporter for five Connecticut dailies then, covering everything from crime to politics. Home, for Gilbert, intersected with monumental and the municipal. Large-scale public sculptures informed her physical place while her father’s work linked her to local politics and language.

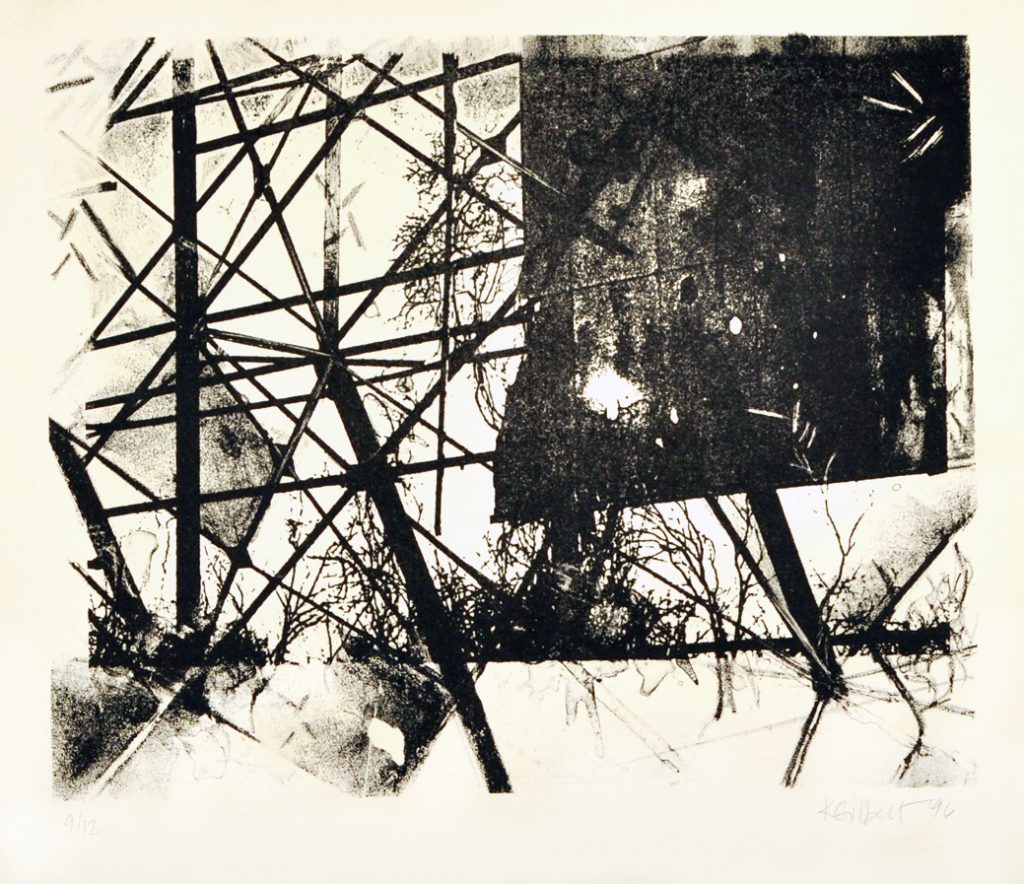

As a student at Connecticut College, Gilbert focused her work on the idea of home and how it’s created. “Since undergrad I’ve continued to observe homeless populations and wonder how one can feel grounded or centered without the stability of a fixed place,” she says now. Researching how nomadic tribes create homes, Gilbert was particularly interested in Laplanders, a Nordic people who traveled in small, family groups as reindeer hunters while living in small tents called Lavvu. Pitching their Lavvu into the ground, Laplanders would consider this temporary shelter their center. Her prints and paintings from this period, such as Tent City (1996), reveal her interest in how shelter shapes the body and vice versa. Similarly, works such as Center (1998) and Drive In (1996) question fixed dwellings and nomadism, assuming a kaleidoscopic aesthetic of blurred colors, fine lines, and abstracted forms.

Kate Gilbert, Drive In. 1996. Courtesy of Kate Gilbert.

Abstraction, as well as impermanence and the insecurity therein, informed Gilbert’s work after she moved to Boston in 1996. While working during the day at the Boston Society of Architects, Gilbert maintained a studio practice. “I made sure I had as much time as I could to paint,” Gilbert says. “[Having] a studio practice is just as important as nurturing a child. If I knew I had a show coming up I could book all of my jobs to work on things…I’d get to the studio at 5:00 am, work until 7:00, go to the nearby gym to shower, and then show up at work at 8:00, do my work, come back. And that’s just what you do when you’re an artist.”

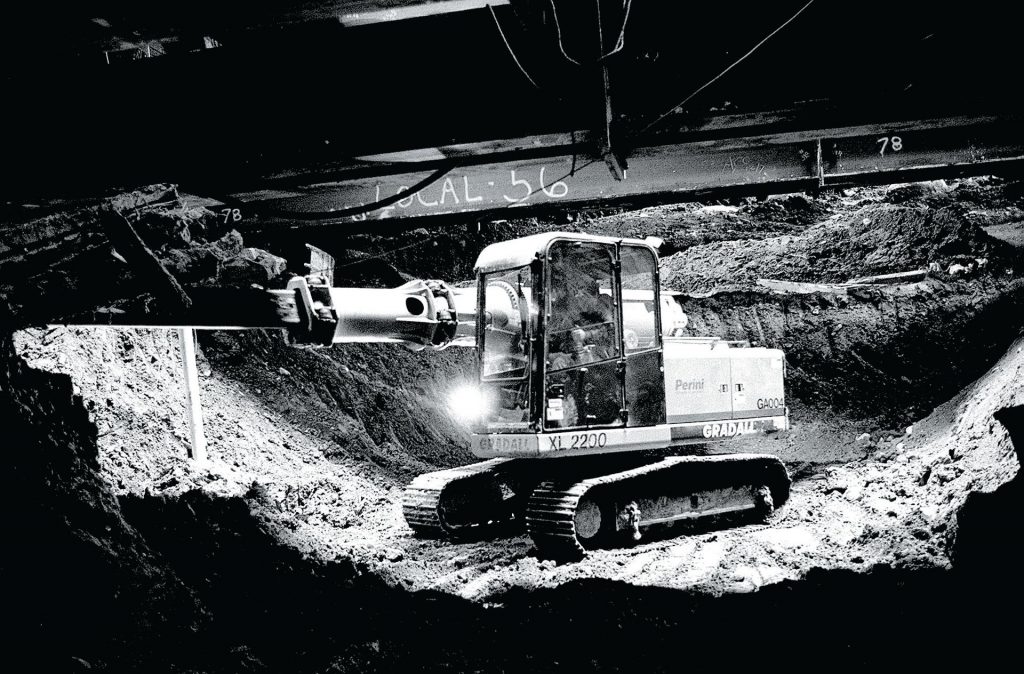

The 1990s were years of intense transition and change for Bostonians, and arguably, especially for the city’s artists. Work to the Central Artery/Tunnel Project, more commonly known as the “Big Dig,” began in 1991, and by the late 1990s, the city was plagued by continuous changes to traffic patterns and pedestrian access. In Fort Point, artists who lived in the neighborhood for decades found themselves in the pathway of the Dig’s progress in the form of vast amounts of concrete and construction. In 1999 Gilbert started working at the Revolving Museum, a public art museum founded by Jerry Beck in Fort Point. “It was my MBA,” Gilbert says of the Revolving Museum, which filled empty buildings with public art projects and provided 100 artist studios as well as gallery space. Gilbert’s studio at 288 A Street was one of these studios. She continued her painting practice there as a legion of construction workers excavated parts of the neighborhood and floated slabs of concrete into the Channel. “There were rats everywhere, everything was chaos,” she recalls. “All of the artists were freaked out about what this was going to do to real estate, and they were right because as soon as everything was done and put away, developers came knocking on doors and people began to leave.”

Work on the Big Dig in 1998. Via The Boston Globe.

Fort Pointers formed the Fort Point Cultural Coalition and its No Art / No Point public art series (2000-2002) to foster awareness of the artist community. No Art / No Point, which Gilbert helped to coordinate, included Eric Legacy’s Exodus (Rat Trap), a cartoonishly large but fully functional steel and bronze rattrap and Jeffrey Smith’s Beret Day. For the latter, Smith gave hundreds of basic black berets to residents of Fort Point to wear for an entire day as they went out and about as usual. Lampooning a stereotype, the performance made Fort Point artists as visible to Boston as the crews of hard-hatted construction workers. “Most work responded to the perception of a looming, pervasive real estate development juggernaut, with the anxiety and uncertainty it caused within the artist community, and the determination by the artists not to be pushed out without first making their presence felt,” writes Jed Speare in the series’ catalogue.

The Big Dig in 2002. Via The Boston Globe.

Boston’s abandoned spaces evolved into retail stores, restaurants and condos as the Big Dig neared completion in the early 2000s. After Beck and the Revolving Museum left for Lowell, Gilbert went back to work at the BSA, where the Big Dig seemed sometimes more conceptual than actual. “As an artist, I saw the very real side of the [Big Dig], like the keys on my keyboard shaking because of the construction,” says Gilbert. Braving the Dig’s disorder, Gilbert and her colleagues occasionally walked under the highway from their downtown office to talk by the Channel. The Big Dig’s transformation of the city would eventually mean more public access to civic spaces around Boston. How could these spaces be used, or activated, by artists for more populist purposes besides shopping centers or tourist traps? “That got me thinking about what we had done at the Revolving Museum with abandoned spaces, [while]these architects were thinking at a much higher level about recreating spaces,” Gilbert says about these conversations. “My little painter brain was thrown open.”

Gilbert saw the Big Dig’s completion and its subsequent transformation of Boston from the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy, where she organized the park’s launch. After the Greenway opened in 2008, a mentor from college, the painter Pamela Marks, encouraged her to apply for a residency in Pont-Aven, France. Like Boston, Pont-Aven is situated on a river; during the late nineteenth century, the small, northwest town was a haven for French Symbolist painters. The paintings that Gilbert made there during the summer of 2009 signify a shift in her artistic practice. While still abstract, these paintings approach physicality and liminality, unlike previous works.

In Knitting Caterpillar (2009), a tight, earth-toned arc of swirls and squiggles drips down into a smaller eddy of muted beige, grey, and brick colors. In dénouement 10 (2009), this composition is revised in more peachy pinks and reds, with the inclusion of a patch of plastic. In other works, the swirl-filled arcs of paint approach the form of a brain. In almost all of these works, the arc forms seem to reach, through elongated drips of paint, for the real world beyond the picture plane. Undone (2009) completes this shift from illusion to reality; here, Gilbert has sliced into the composition itself, cutting curls into the painting with an Exacto knife. Signifying fluctuation, Undone was the basis for Gilbert’s first solo show in 2010.

Kate Gilbert, Helen F and the Alligator Man, 2011. Oil on canvas, Duralar. 25 x 25. Courtesy of Kate Gilbert.

Later that year, Gilbert completed Spirit Boat (2010), a graceful work on paper that she sees as the perfection of her “signature swoop,” a calligraphic-like mark inspired by Egyptian hieroglyphics. Along with Helen F and the Alligator Man (2011), undone and Spirit Boat pushed Gilbert to articulate the meaning of her work through multi-dimensional forms. “It might be something about getting a little bit older, but I want to contribute more,” says Gilbert. “And painting to me feels like a very gratifying, self-centered, self-focused activity.”

When she began at the MFA program at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 2011, Gilbert focused solely on multi-dimensional work. “I threw myself into video,” she remembers. Absorbed with the idea of making a space, Gilbert progressed from video into installation and sculpture. This progression is clearly seen in videos like The Rogue Tent: A Studio Intervention (2012), in which Gilbert pitches a tent by inflating it through an HVAC system. Barbara Gallucci, who would become Gilbert’s thesis advisor, identified her installation work as sculpture. “It felt like finally someone was telling me who I was and it felt natural,” says Gilbert.

From there, she concentrated on making objects or spaces that teeter on fantasy or absurdity but are steadfastly engaged in reality. Liberated from painting’s formal constraints, Gilbert began crafting new forms from objects originating in the public sphere. In Shell Jackets, a coat is not just a tool for warmth or cover, but for courage. Cut like an overcoat, the Shell Jackets are fitted with hand pumps in the pockets to inflate the shoulders. Wearing a Shell Jacket feels chic, and pumping it up with air feels powerful; an exaggerated version of 1980s shoulder pads, the Shell Jacket’s swelled shoulders instills a feeling of control from within. Similarly, in her Hoods, Gilbert includes a brim, molded to direct the wear’s vision and stocked with a survival kit for security. Lined with fleece, the Hoods are meant to keep you cozy while softening noise from the street. In Tent Dress, a woman’s shelter becomes her clothing, allowing to her take literal cover from the elements wherever she goes. These works coalesced in HIDE: SEEK, Gilbert’s thesis show. Simulating a clothing line, Gilbert simulated the polish of a retail store in her installation at Carroll and Sons in the spring of 2013, complete with a glossy catalog with marketing text she wrote. Unrestricted by surface and illusion, the works in HIDE:SEEK instead fashion a mirage of our reality through the very products we use to navigate it.

Kate Gilbert, HIDE:SEEK, Mixed media installation, SMFA thesis show at Carroll and Sons, May 2013. Courtesy of Kate Gilbert.

Safe survival of the world thematically threads through much of Gilbert’s video work. In Alone Together tent dress (2014), a woman treads through a patch of urban grass, to erect a private, secluded place in public, before packing it all up and continuing on. The tent motif directly responds to displacement here, as it's hard not to consider the form without remembering its function as shelter for refugee communities across the globe. The tent’s impermanence and fragility are underscored by the concrete and steel structures that surround it. Ripples: Generations of Fear (2013), included in HIDE:SEEK, presents a lone woman, outfitted with a Shell Jacket and Hood, cautiously traversing a lushly rural landscape. An anxiety marks her caution as if she is evading capture. But instead of picking the path of least resistance, the woman arduously steps through the terrain and, curiously, stops to carefully dust a solar panel. True rest only comes as she, sans Shell Jacket, sips a scotch and relaxes against the skeleton of a rusted truck.

Kate Gilbert, still from Ripples: Generations of Fear. Courtesy of Kate Gilbert.

Both Alone Together and Ripples are rooted in an inherited past. The tent’s shape in Alone Together recalls the Lavvu of the Laplanders, who are connected to Gilbert through her Finnish ancestry. And Ripples extrapolates and heightens fears or anxieties passed down from mother to daughter. Familial archives are the source for Father’s Farm, Broken (2015), a work that examines the patterns of resource usage, specifically land and water, over several generations. Culling home movies from 1937 to 1978, Gilbert, in Tonal blues, greens, and greys, presents her family swimming in a pool or beach, gardening and watering plants, climbing and swinging on trees. Punctuating this footage is shots of waterfalls from a vacation. All of these are so-called normal, American leisure activities; however the mood of the video is less idyllic than it is repentant. Inherited natural resources, water, and land alter their course as we use them.

“Video is so accessible, and I want to be working on the thing that everyone gets and knows,” Gilbert says, discussing her recent work with asphalt, a material she plans to continue using through photography, video, and performance. In the last few years, she’s taken to finding and using broken asphalt chunks to create delicate, fanciful works that seamlessly bring imaginary realms into the real world. Using modeling turf and gold leaf to suggest deposits of resources (and therefore money) Gilbert transforms pieces of broken infrastructure into an object of value. As she has with performance and in the video work, Gilbert creates a character or fictional narratives as she approaches the asphalt. “I think of this as a little world, floating in outer space,” she says. “[Nature] keeps shifting and messing up what we try to order—man goes along and puts down a flat, concrete road, and then a lot of rain comes, then it freezes, and then the thing cracks.” Gilbert’s work activates that crack.

Kate Gilbert, From the Sidewalk Series. Found concrete and asphalt, model scenery, and gold leaf. Courtesy of Kate Gilbert.

Housing, redevelopment, transportation, and community are currently hot-button issues in Boston as the city moves on from the Big Dig. But these aren’t new issues for Boston or specific to the city. They are global topics and are largely informed by decisions and actions made by generations before now. So how can we solve them, or allow for alternatives to the status quo? “If we take this thing called contemporary art out into the streets, we might be more effective at creating appreciation for it, which in turn leads to demand, which leads to more art, which leads to a vibrant city,” Gilbert says in reference to Now and There, the non-profit she established and now directs. Gilbert doesn’t really differentiate between her art practice and the work of Now and There, as both are entrenched with creating new spaces for observation, reflection, and exchange. She is driven to enhance, to add, to our imperfect world.