STUTTER @ TATE MODERN

A stutter is defined as an involuntary interruption, repetition or agitation of human speech. At the Tate Modern, the concept of stutteris explored in terms of the human thought process, verbal and visual communication, as well as our physical and emotional experience of this kind of finicky disruption.

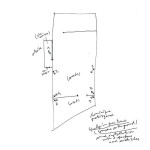

The main room in the Level 2 Gallery is dominated by a sound installation by Dominique Petitgand's installtion, Quelqu’un par terre (Someone on the ground). When I first entered the corridor I actually thought that there was some kind of commotion going on outside, construction or installation clamor. The loud echoes of his composite audio create a stark, metallic reverberation through the gallery. And the lingering sound of wind and whisper of human voices in between the harsh clashes of audio are haunting.

Harsh audio can interrupt our train of thought and make us feel defensive and physically tense. Yet the overall effect of Quelqu’un par terre is really a unique lesson in patience. Listening for several moments to the seemingly incoherent audio reveals a strange composition of white noise and the occasional recognition of a familiar sound or quiet whisper. Apparently, Petitgand collects sound fragments, which he pieces together in a purposefully confusing arrangement that plays out of separate speakers throughout the gallery. Moving closer to an individual speaker changes the sound experience and allows us to discern an individual sound byte. Petitgand strives to evoke a response in listeners hoping to catch a particular sound that resonates with a memory from their own experience from the cacophony of simultaneous sounds.

Anna Barham’s A Splintered Game is a light installation that actually plays off the disorienting cadence of Petitgand’s audio. Barham uses a randomizing computer program to synchronize an erratic rhythm of flashing light in thin fluorescent tubes. Amidst Petitgand’s crashes and whipping sounds of wind, Barham’s piece evokes a damaged light fixture after a violent storm. Yet the elegant geometric design helps distinguish the piece as its own entity, as does the decision to display the piece neatly on the floor next to its electronic lifeline. The arrangement presents ordinary industrial objects in a less familiar way, which makes the unusual pulsating flickers more unexpected, disarming and visually interesting. While the light pattern seems chaotic, the piece looks strangely methodical at the same time. The piece evokes contradictory reactions simultaneously, which pulls the viewer in different directions.

Michael Riedel’s Filmed Film Trailer is a complex compilation of imagery that draws in the viewer struggling to comprehend the storyline. The film is comprised of numerous film trailers that were recorded using a defective video camera. Images come in and out of focus, move or darken out completely, and several segments of video appear to be vibrating. Riedel edited the piece down to seven minutes from an original 16 hours of footage. The result is a shaky and frenetic flash of imagery that looks like a recovered lost movie. There is a frantic sense of trying to communicate a large quantity of information in as short a time as possible. Interestingly, this film echoes the same sense of contrived history as another film in the Tate Modern galleries.

In the collections, History of Nothing pieces together work of British Pop artist Eduardo Paolozzi with help of filmmaker Denis Postle. The collaborative History of Nothing presents a sequence of collages and photomontages emphasizing Surrealist imagery and examples of modern machinery. Both the pace of the film and the strange soundtrack are meant to mimic tired historical documentaries. But because the imagery focuses on mechanical objects and moves so slowly, it doesn’t seem to connect to the real world. Therefore the film reads more like a visual homage to Paolozzi, and less like a recount of human history. Conversely, the eerie film by Riedel does read like a condensed, frantic narration pieced together from lost footage.

To explore the issue of language, Riedel also contributed four canvases from his project, change of modern, which features the letters “Modern” from the gallery logo, cut up and refashioned on large white canvases. The idea is to open up the possibilities of abstract composition within these characters, and for “the word ‘modern’ to be read as an ever changing moment.” However the conventional abstract shapes makes it difficult to see that the origins of the work lies in language, without reading all the fine print. The works read more like an ode to Robert Motherwell, which actually seems appropriate for an exploration of modernism, but the theme of words as experience gets lots in translation. Perhaps if the characters crept into a gradually increasing abstract form on each canvas, it would read as a hiccup in human language being expressed visually.

The idea of language becoming more experiential isn’t necessary expressed in this single piece, but is definitely expressed in this exhibition as a whole. The word stutter evokes a very specific idea and in this exhibition, an experience, yet it does comes across in the works presented by these very dissimilar artists in a wide range of mediums. This exhibition extends beyond into a kind of nameless sensation where the title becomes only a placeholder for confusion, recursive definitions, and repeated sensation. All language is more than its definitions, and symbolic of larger ideas. In this way, it expands the definition of the word, and introduces something usually confined to language into other forms of experience and communication.

- Michael Riedel, exhibition view of Four proposals for the change of modern, 2009, Staedel Museum, Frankfurt, 2009. (Photo: Norbert Miguletz)

- Anna Barham, A Splintered Game, 2008. (Electronics: Andrew Welburn)

- Dominique Petitgand, sketch for the installation of Quelqu’un par terre (Someone on the ground) at Tate Modern, 2009. Courtesy of the artist and gb agency, Paris.

"Stutter" is on view until August 16th at the Tate Modern, located in Bankside, London, England.

All images are courtesy of the artists, the Tate Modern, Norbert Miguletz, and gb agency, Paris.