It is now almost ten years after the 2008 Beijing Olympics, and sixteen since China joined the World Trade Organization. Three decades have elapsed since the Tiananmen Square protests, and half a century since the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. For contemporary Chinese artists, art is a valuable tool for processing both the rapid changes and lingering trauma of the last five decades.

This art deserves the attention it is currently receiving from institutions in the United States, despite many works being difficult for Americans to understand, or even accept. The Guggenheim’s Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World (through January 7, 2018) faced outcry over allegations of animal cruelty, and several works were withdrawn from the exhibition before it opened. In Boston, Chinese Dreams at Massachusetts College of Art’s Bakalar & Paine Galleries (through December 2) is more intimate in scale, but includes works as shocking to a Western audience for the immediacy of their subjects’ suffering as those pulled from the Guggenheim.

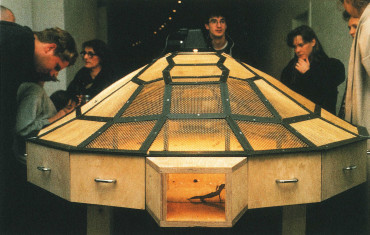

Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the World, 1993. Wood and steel structure with wire mesh, warming lamps, electric cable, insects (African millipedes, house crickets, goliath beetles, hissing cockroaches, lubber grasshoppers, and stag beetles), leopard geckos, and Italian wall lizards, 150 x 270 x 160 cm

Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

© Huang Yong Ping.

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World is impressive in sheer scale. Works by seventy-odd artists occupy the entirety of the Guggenheim’s spiral ramp, as well as two tower galleries. Extremely comprehensive wall text attempts to reorient Western visitors to see not just art but history from a new perspective. The most well-known artist in the West, Ai Weiwei is invoked throughout, offered like a compass for visitors in unfamiliar territory. Several of Ai’s works are on view, including his famous Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn triptych. However, it is not Ai Weiwei but Paris-based Huang Yong Ping whose work both gave the exhibition its name and fueled the fires of controversy. Huang’s 1993 Theater of the World references globalism, Chinese cosmology, and chaos in the form of a turtle-shaped cage housing live insects, snakes and lizards that fight and eat one another. Faced with pressure from animal rights activists, the Guggenheim is exhibiting the cage without animals. Meanwhile, it completely withdrew Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s video Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other.

There is still plenty else to see that is unsettling to Western eyes as violence and mortality are explored in a nightmare logic that swings between uncomfortable particularity and all-encompassing conquest. Take “X?” Series No. 2, Zhang Peili’s large painting of surgical gloves made during a 1988 hepatitis epidemic in Shanghai, or his video installation Uncertain Pleasure II, in which twelve TV screens show hands scratching flesh at close range. Qiu Zhijie’s The Present Continuous Tense allows viewers to watch a live feedback loop of themselves embedded within a colorful funeral wreath, where they appear like ghosts at their own funeral. At the end of the exhibition, there is Gu Dexin’s 2009-05-02. These 35 panels mounted near the ceiling in a tower gallery spell out a stunning indictment of history in vermillion characters (typical of campaign signage in China): “We have killed people we have killed men we have killed women we have killed old people we have killed children we have eaten people we have eaten hearts we have eaten human brains we have beaten people we have beaten people blind we have beaten open other people’s faces.” Gu’s panels are the showstopper Theater of the World strived to be.

Zhang Huan. To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond: performance, Beijing, China, 1997. DVD Total Running Time00:05:57. Photo courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery. © Zhang Huan Studio, courtesy Pace Gallery.

As at the Guggenheim, the body is a major theme and performance is a preferred medium in Chinese Dreams at MassArt. Bodies of migrant workers bathing in a pond take on collective power in Zhang Huan’s 1997 To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond: Performance, Beijing, China. In 12 Square Meters, Zhang sits naked in a public toilet, coated in fish oil and honey until flies cover his body—this was performed in tribute to Ai Weiwei’s father Ai Qing, a poet who cleaned toilets during the Cultural Revolution. Song Dong muses on traceless mortality in A Pot of Boiling Water, a performance in which he poured out hot water whose ghostly steam disappeared while he walked away. Ma Qiusha explores her own body’s capacity as a pain- and memory-bearing vessel in From No. 4 Ping Yuan Li to No. 4 Tian Qiao Bei Li. Ma recounts pressures to succeed as an only child under China’s one-child policy. She speaks slowly, a razor blade hidden on her tongue.

Not all the works on display at MassArt are so body-centric. Hai Bo’s contemplative photography and Fred Han Chang Liang’s intricate sculpture Autumn Biophony are both worth note for their rural outlook and focus on nature, respectively. Chinese Dreams also delves into the ambiguities of intellectual and religious existence in post-revolutionary China. Yet the more shocking and somatic images are the ones that leave a lasting impression. These are the images that deal directly with the commonly lived aspects of modern Chinese history that Western audiences find difficult to fathom, and that both exhibitions seem intent on excavating.

Fred Han Chang Liang. Autumn Biophony, 2017. Cut paper, mirror. Photo by Eduardo Rivera, courtesy the artist and MassArt.

Without knowledge of modern China and this lineage of artists who act from places of protest and trauma, this fixation with violence, pain and death can seem oppressively dark, even cruel. From certain points of view it is, and some of these works will haunt unprepared American viewers. In these two exhibitions, Chinese artists are presented to Western audiences as wrestling with the pain of revolution. Given the ideological turmoil China has seen in the last fifty years, artists there work to reach a cathartic purpose, like a doctor who must prod a wound and open sores to heal their patient.

Chinese Dreams is on view at MassArt through December 2, 2017