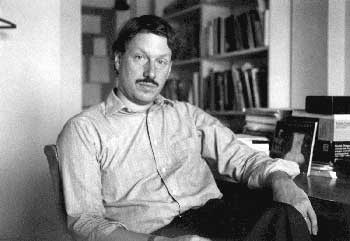

James Elkins is a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and author of numerous books on a wide range of subjects, including "Why Art Cannot Be Taught", "The Object Stares Back", "Master Narratives and Their Discontents", and many more. His ideas about how we think about, teach and discuss art are invaluable for anyone who is involved with education or dialogue in the arts. Below is an email conversation with Mr. Elkins about his work and interests.

MN: For those that may not be familiar with your work, can you talk about how you came to write about the way we teach art, how we consider art criticism, and why it is valuable to re-evaluate our approach?

JE: I was plunged into the weird world of art schools straight out of the University of Chicago. I was ABD (finishing my PhD dissertation) when they hired me, and the first lecture I had to give was on sexuality in the Renaissance. At the time I tended to wear silk-lined pants and white shirts -- a kind of upscale U. of C. uniform. So the art world was a huge shock. Even now, over 15 years later, I still think that people who come out of universities and teach in art schools either sink or swim: it takes more than a slight adjustment. It requires a major overhaul of your assumptions about art, its history, what needs to be taught, and how teaching work for artists.

That first year I was also teaching a course on the Renaissance in general. (Since that first year, I have never taught Renaissance art, even though it was my specialty.) I asked students to make projects for the class, so I could see what they cared about. One student got interested in the Art Institute's Tintoretto, which is a depiction of the rape of Lucretia. In the painting, her pearl necklace has broken, and the pearls are scattering in midair. I assigned all the usual readings for the student -- stuff I had learned in graduate school -- and she produced an artist's book as her project. In the book she had put all the Xeroxes she'd been reading, gessoed into the pages so they could not be read, and every couple of pages she had made a painting based on the Tintoretto. Her paintings were either big blow-ups of the pearls (one big round droplet per page), or enlargements of Lucretia's knee, which the student thought was shaped like a pearl. That was my Eureka! moment. It made me realize artists do not need to be taught art history the way that art historians think they do. They have idiosyncratic, oblique, eccentric, unpredictable, a-historical, and just plain crazy uses for history. That experience was the beginning of the end of ordinary art historical pedagogy for me.

MN: In "Why Art Cannot Be Taught", you take a long hard look at art schools and the way we teach (or fail to teach) art. Can you talk about how you came to this project? Since publishing the book, have people come forward that have changed or softened your view, or re-enforced it?

JE: That book developed over the years, as I thought about art school critiques. At the end of that first semester, in 1989, I was exposed for the first time to art school critiques from the point of view of a teacher. (I had an MFA, so I wasn't completely surprised!) I realized that the teachers have no special knowledge, and -- perhaps even worse -- that they have no idea how critiques should work, because -- the most astonishing discovery for me -- there are no books on art critiques. There are no manuals, no art-education essays, no guidelines of any sort.

That book is about reasons why art can't be said to be taught: but really, it centers on critiques, and it is a kind of manual for making sense of critiques. (Or at least as much sense as it's possible to make, which isn't much.) I have had various reactions to that book, but my favorite is that about 3 years ago, some sculpture students in RISD refused to have their final critiques, on the grounds that I had supposedly claimed critiques are nonsense. (I don't claim that in the book, but I was happy to think I'd started a protest.) I don't know what happened to those students -- I suppose they must have changed their minds in order to graduate.

MN: Having just gone through final critiques of the semester, I sometimes feel that critiques often do border on nonsense, or at least (as you have stated in your books) meandering and unstructured. Have you developed any new strategies for thinking about critique as a form? Or, since much of the critique that happens outside of school is equally unstructured, is it an exercise in futility?

JE: Well, I still think that one of the best things to do with a critique is to tape it, and then type it out, and then read it as a play. That's a lot of work, but it lets you slow everything down, and think about each statement with microscopic precision. You can ask why each person said what they did, and what assumptions might lie behind what they said. In classes, I have done this with students playing the roles of the critique panel; we show slides of the artworks so we can check what people said. Sometimes a 45-minute critique can take 3 hours to read through, because we often stop and discuss the motivations for various things that get said.

Now I know that advice is hard to take, and a simpler (and less accurate) method is to videotape the critique, and just keep hitting pause. It takes hard work to figure out what happens during critiques, but I think it can be done, if you make the effort.

I notice I haven't answered your last question. Are critiques "exercises in futility"? Not if it's a matter of trying to get information from them, or seeing how they make sense. But they are often futile in terms of their effect on artmaking or on careers. Everything I said in the first two paragraphs is about comprehending the logic of the critique (motivations, assumptions, reasoning, narrratives). I doubt there is any correlation between the logic of critiques and an artist's career or the quality of the art. I also doubt that critiques can be said to increase a person's self-awareness of their own art: and I even doubt -- I'm making a list in order of increasing pessimism -- that self-awareness makes better art.

MN: One of my favorite passages [1] by you is an imagined text that a school might print if they were 'honest' about how art institutions function? Do you feel there is an inherent dishonesty in art education? Aren't all institutions, whether they teach art or not, somewhat disingenuous in their promotional material?

JE: Well, a medical school, for example, is not dishonest in advertising that it teaches certain commonly agreed skills and knowledge. A degree in physics entails the mastery of a body of knowledge whose limits are well understood. No one claims medical schools create great doctors -- they just permit people to be competent doctors. Likewise no one claims a PhD in physics will make you the next Einstein. If there is "dishonesty" in art schools -- and that's not a word I would use -- it is in the implication (rarely stated, always implied) that the school teaches art. What is taught, I think, is a certain way of talking and thinking about art ("artspeak," to put it cynically), together with a large set of social skills and connections. Art schools also teach skills, but as Howard Singerman has pointed out, they don't do that in any reliable way, and skills are often devalued in any case.

I don't use the word "dishonesty" because I don't know any art departments or art schools that say directly, "We teach more than just skills." But promotional materials are often "somewhat disingenuous" and in a sense they have to be, because students and teachers share a common hope and interest in something that (despite all the changes in the artworld since the days of art academies) still needs to be called "high art" or "fine art."

These are general thoughts, and they can go in many directions. I'll just end by saying it is worth reading the promotional material put out by art departments and art schools very carefully, word by word. Those phrases are usually the product of various committee meetings, and they seem empty and overly optimistic at the same time: but they are actually the sum total, the final result, of public debate on the question of teaching art. In other words: no one really know what studio art education is.

MN: You've suggested many times in your writing, including the title of your latest project "Art History Versus Aesthetics", that the type of critique undertaken in art schools by students and teachers is fundamentally different than that taught to art historians, who often become art critics. How do you think this frames the discussion of contemporary art? Is there a difference when the critique is offered by people who have studied in art schools, rather than as art historians (such as on Big RED & Shiny)?

JE: You know, I'd like to say there isn't a difference, but there is. People who work exclusively in the art world and have little contact with studio critiques -- for example, most art historians, people who come from philosophy like Arthur Danto, many gallerists, many curators, some newspaper critics -- tend to think that there is only one kind of interesting talk about art: it's a kind of articulate, fluent, sometimes even eloquent way of speaking that involves what used to be called "philosophemes" and lots of references to the histories of art and criticism. When I say "one kind" obviously I mean that very loosely, but still it is quite different -- surprisingly different, for some people -- from the kind of talk that can happen in studio settings and studio critiques. There the talk is about gesture, form, and feeling. It is a loose and rough kind of talk, not always eloquent. It does not make any consistent or reliable use of art history -- the references to art historical precedents in studio talk can be garbled, or inappropriate. It has a lot to do with the emotions of working, the feeling of being in the studio. It is impressionistic and personal. It verges, often, on the non-verbal, by which I mean that people in studios do as much pointing and gesturing as they do analyzing. To a person trained outside the studio, or to an art historian or philosopher who does not visit the studio, this kind of talk simply sounds unhelpful. It does not sound like an entirely different kind of talk: it sounds like a low-level, uninformed, probably fairly uninteresting version of something that is done better in publications and other public fora. Or it can sound like an old-fashioned kind of talk, since it has a lot to do with the stuff that happens in the studio, instead of with politics. As you know, I think studio talk is absolutely fascinating. The problem, from an outsider's point of view, is taking it seriously. (And do I need to add I am not talking about talk in famous people's studios -- in Jeff Wall's studio, or even Damien Hirst's? Those people are already public speakers. I mean ordinary talking, ordinary studios throughout the world.)

MN: With the explosion of blog culture, there is a lot more art criticism and discussion coming from 'regular' viewers, rather than a select critical elite. Do you think that this is a good or bad thing? Will it affect the type of criticism offered by more traditional media?

JE: Here I have to switch allegiances, because I think that "regular" viewers often muddle talk about art. In Chicago, where I work half the year, there is a TV program called "Check Please!" On it, three or four guest reviewers talk about restaurants they've been to. I think that program is horrible, because most of the time those "regular" diners don't know anything about the cuisines of the restaurants they are judging. The implication throughout is that you can just have good taste without knowledge. If you go to a Southern restaurant for the first time in your life, you're as capable of judging fried tomatoes as the next person -- well, I don't think so. There is such a thing as knowledge in the art world, although it often gets swamped by calls for democratization. It's fine to keep an eye on elitism, but it's not a good idea to suppose that art can be judged equally by everyone.

MN: Your newest book is called "Master Narratives And Their Discontents". How do you define 'master narratives', and what led you to write this book?

JE: Thanks for mentioning that. The idea was to set out the principal theories about when modernism and postmodernism began, and to do it in as straightforward and lucid a manner as I could. Theories of art in the last 100 years are very confused and entangled, and I thought it would be a good idea to risk oversimplifying in order to try to make some order out of the chaos. Needless to say I don't solve anything in that book! But I hope I set out a clear schema for other people to respond to. The book is vol. 1 in a series of 6; five other authors will be writing their own theories about the shape of 20th c. art.

----

[1] - The quote referred to in question four comes from "Why Art Cannot Be Taught", page 104.

"Art department fliers... usually list the famous artists who studied in their department or school. It might be more honest and thought-provoking to go ahead and list famous graduates in the college brochure, but to preface the list with a disclaimer - something like this:

Although these artists did study at our school, we deny any responsibility for their success. We have no idea what they learned while they were here, what they thought was important and what wasn't, or whether they would have been better off in jail. We consider it luck that these artists were at our school.

In general we disclaim the ability to teach art at this level. We offer knowledge of the art community, the facilities to teach a variety of techniques, and faculty who can teach many ways of talking about art. But any relation between what we teach and truly interesting art is purely coincidental.

Such a flier might add, in the interests of full disclosure:

We will not discuss this disclaimer on school time, because our courses are set up on the assumption that it is false."

Links:

James Elkins website

James Elkins' books are available at Amazon.com

All images are courtesy of the Mr. Elkins.