With a background in linguistics and work experience as an interpreter for several years in China, Furen Dai’s artistic practice centers on language and the culture built through it. She reflects on various forms of interpretation in her work with video, sculpture, and performance. In her previous work as interpreter, Dai was often in a position between two cultures attempting to examine where these two cultures met, overlap, and where they differentiate. In this interview, Dai and I spoke about the interdependent themes of language and cultural politics in regard to economic conditions and performance art.

Silvi Naçi: What brought you to the United States? How did your work expand from working in Linguistics in China and Russia to working in the arts today?

Furen Dai: My undergraduate education focused on Russian linguistics. I worked for several years as an interpreter both in Russia and China. I was always interested in art and spent some time making art on my own while I worked as an interpreter. It is difficult to start pursuing art as a career at an older age in China. There is a strict school system in which many students start learning about art at a very young age in order to hone their craft and skills. I moved to the United States to experience the school system here and to learn more about contemporary art. In the beginning, I interned for a dance company called Urbanity Dance. My boss, Betsi Graves, encouraged me to pursue art. I took a few classes at MassArt and the MFA. Later, I enrolled in the post-bac program at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University (SMFA) where I was working mainly in painting and collage – processes that really opened my mind. After my post-bac year, I began graduate studies at the SMFA, where I started by working in painting and sculpture and then expanded into video and performance.

Furen Dai, 500 Years Pots.

SN: What correlation do you see between identity and the creative processes of sculpture, collage, text, video and performance? Does it change with each medium, and how does each technique influence and inform the way you approach artistic cultural production?

FD: I feel that the medium is the language and the concept is the idea. I use the language to express my ideas. I always start with the concept then by utilizing different mediums I build the idea. Being in dialogue with other artists has pushed me to experiment with different materials and approaches. I quit my job as an interpreter because I felt like I was functioning as a machine, and that I didn’t have my own voice in the translation process. After five years of working and studying in the United States and looking back at my history, I have a different understanding of what it means to be a translator. I appreciate the importance and relevance of understanding both cultures involved in the translation from my position. Now, I actually love the opportunities for interpretation. I have also integrated it into part of my artistic practice. Looking back at my journey and this process, I can understand what has lead me to investigate my artistic approach involving language.

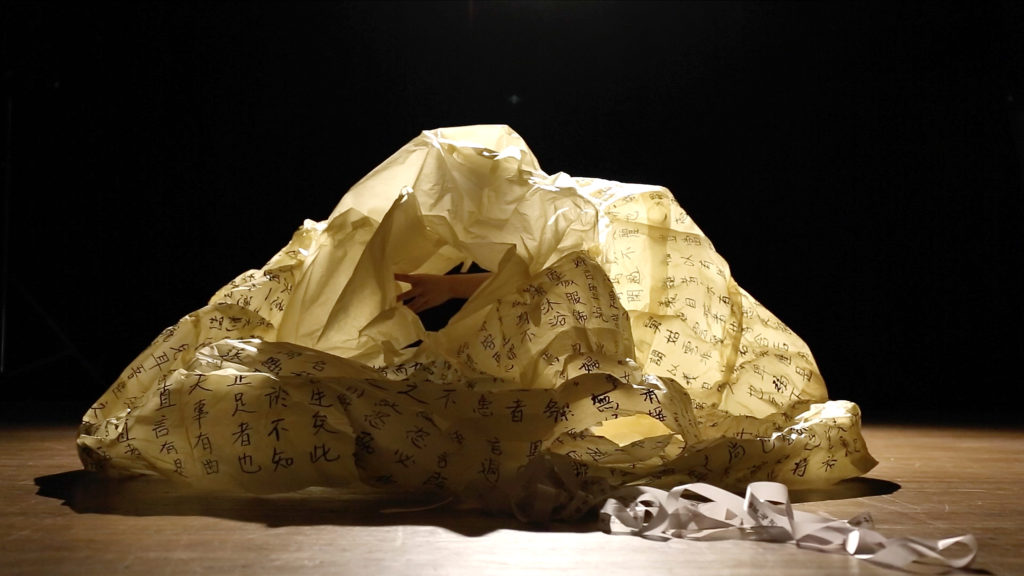

Furen Dai, Language Product.

SN: Can you speak about the socio-political and cultural justice work you are engaging in and creating in the United States versus creating the same work in China?

FD: First of all, if I was living in China I probably wouldn’t be making art. It helps to be looking at my own culture from a distance. It almost feels like looking at something unknown, full of curiosity. If I was making art in China, I probably wouldn’t be questioning a lot of things because I would be accustomed to the situation. Returning to China with fresh eyes in 2016, I was able to see a lot of familiar things in an unfamiliar way. That’s when I started questioning “Why it is the way how it is here?” In my research for Language Product film, the books written by Chinese scholars about this secret women language had no reference to the real socio-political context in China.

I wondered why no one had thought to write about this important aspect, then I recalled in China we are not used to questioning or challenging the established systems and accept the way they are.

Furen Dai, Commandments for Women I, 2015.

SN: Your voice as artist and individual comes through in the interpretation of image making and documentation of both traditional and contemporary cultures in China, which ultimately boosts the voices of the women in the cultures you emphasize. Can you talk about the female labor in relationship to this secret language?

FD: While working on Language Product, I went to China to film the women who are educated in NüShu (Woman Script) - a secret women language originated in Jiang Yong, China around 400 years ago. I watched them perform in each room of the museum, one of them writing, another singing, repetitively for each visitor. I felt like they were working as performance machine. After visiting the museum every day, I witnessed many male photographers directing the women to perform a certain way for their photographs. When they noticed my return each day, one of the women invited me back to her house and offered to cook for me. We spoke at length about the history and the research regarding this secret language. She expressed hatred towards the language and wished she had never learned it. She ultimately felt trapped.

Furen Dai, Message through Generations.

Currently, the local government is applying for a cultural heritage status in regards to the language in order to attract more tourists to the museum. Many young girls choose not to learn this language so they are not trapped by this system.

I began this work because I wanted people to learn more about the culture and history of the language since there isn’t much research on the subject, and the existing material is mostly written by men. Only the positive and commercial aspects of the language have been highlighted and prominent to the public. However, most written materials completely discount the aspect on how these women feel about this ‘profession’ and how their life-consuming labor is being ignored or taken for granted in their culture.

Furen Dai, 500 Buddhas.

SN: When we met, you were creating a participatory piece titled 500 Buddhas. Can you talk about the idea behind it and how the work was then distributed?

FD: The work first took place at Lee Mingwei’s Living Room Project at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Each of the small sculptures had a note underneath, written in Chinese about a skill the Buddha has. As the people took a piece that resonated with them in shape and color, I translated the meaning of the skill to them and asked them to take a picture of where they placed the sculpture in their home, in order to understand how each person interpreted the meaning of the piece.

SN: Can you talk about the element of ‘trust’ being transferred and the translation between different cultures? What is lost or gained in the process of translation?

FD: Before, I always thought there was not a lot of space in translating the syntax of two foreign languages, although, at times when I didn’t understand what people were saying in Russian, I would start making up some of my own interpretations. Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about what’s lost and gained during the translation and how gender plays the role in this process. I have started realizing there is actually a lot of room in the interpretation and how each individual translator’s cultural background and character impacts what they are translating. There is definitely trust from both sides towards me when the participants have no clue of another language. He/she is dependent entirely on me to translate both the culture and the language.

When I started working as an artist, I realized that the space for interpretation is very important and it’s where your voice and imagination as a translator comes in. After my site visit at the village in China, I came back and spent a lot of time thinking about how I should process all the documentation and information. With this heavy topic, it was a real challenge for me to retell the story. I chose to create a language production factory, where women create language as souvenirs, and at the end sewed themselves into part of the final product. Collectors brought them home without knowing anything about the meaning of the language and the women inside the product. During my reinterpretation of what I saw and experienced in the village, I was definitely struggling with losing some of the heaviness related to the women’s situation, but I thought my approach would evoke some sort of understanding what I saw from a different perspective.

Furen Dai, Language Product, 2016.

SN: I know your mom is a great support system for you, what’s it like working with her?

FD: I love working with her. She is a huge supporter of my work. I first wanted to work with my mom in an earlier piece: Message Through Generation – where we are talking about a book called the commandments for women, which is a book written by a woman scholar from China in around 100 C.E. describing how women should behave in society and at home. I had a conversation with my parents about it, my mother agreed with some of the rules and my father agreed with all of the rules about how women should behave. I disagreed completely, and that’s how the piece developed. After that piece, I brought her more and more into my work.

Furen Dai, Fortune Cookies, 2017.

SN: What is your fascination with the fortune cookie in your latest work?

FD: I felt the fortune cookie is a symbol for the first cultural difference people encountered both for Chinese people coming to the United States or Americans going to China. It is a very strange culturally combined object for me.

I started thinking about who are the people behind the production of the fortune cookie: Who invented it? Under what circumstance did they invent this? Who is the person writing all the fortunes? After a lot of research, I found that most of the factories producing the fortune cookies are based in the United States, particularly in San Francisco. I started thinking how much this object is being charged with people’s trust and emotion and how the process of producing this object is through mass-production and machine culture. I also started thinking what if someone received the fortune and wanted to write back and have a discussion around it. Who should they write to? I’ve created a traditional Chinese kitchen where the woman attempts to communicate with the person who has written her fortune, to then only receive back formulaic responses.

Furen Dai, Commandments for Women I, 2015.

FD: SN: Who is an artist you’d love to collaborate with?

FD: I really want to work with people from different disciplines. I would love to collaborate with Mika Rottenberg, because I’m really inspired by her way of weaving an imaginary architecture space inside people’s brain. Also, I just had a studio visit with Laine Rettmer recently and looked at her new work. I am interested in the way she shoots video. Her background as a theater director working with opera singers is very different than my approach to video performance, so I’d love to collaborate with her as well. I am very open and always a champion for collaborating with people whose work is very different than mine.

Furen Dai, Commandments for Women II, 2015.

SN: Do you have a dream project?

FD: Yes. if possible, I would really want to travel around the world, collect and document all the languages that are going extinct or already are, gather stories, songs and develop work about each of them.

Furen Dai is a multimedia artist based in Boston, MA, working mostly in video, performance, sculptural installation as well as painting. Dai has presented exhibitions nationally and to a wide range of audience internationally in Italy, Argentina, Russia, China, Vietnam, Spain and more. She holds a Masters in Fine Art from The Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University (Boston, MA) and Post-Bac Certificate in Studio Art, a Graduate Diploma in Entrepreneurial Management from Boston University School of Management (Boston, MA), and a Bachelor of Russian from Beijing Foreign Studies University (Beijing, China). Forthcoming, Dai will be part of the Listhús residency program in Iceland, Art Omi in New York, MASS MoCA in North Adams, along with presenting her work in numerous group exhibitions. She is currently a Post-Graduate Teaching Fellow at School of The Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University.

To learn more about Furen’s work, please visit furendai.com or follow her on Instagram: @furendai

STAND UP – Women* You Should Know: is an interview and lecture series program where women* of various marginalized cultures come together to share conversations about artistic processes, education, community, and contemporary art practices. [Women*: open to anyone who identifies with this word.]