Italo Calvino’s 1972 book, Invisible Cities, has long proved a spark of inspiration for writers, artists, and curators. His imagined dialogues between Marco Polo and Genghis Khan, as Polo attempts to describe the cities he has seen on his travels (or cities he imagines he has visited), proves a fertile ground in which to explore variations of many kinds. There is no other book quite like it, though more picaresque books of travels, including Polo’s own, that of Friar Odoric, who toured Asia some 20 years after Polo (both nonfiction, in parts), and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (fiction) are among its many ancestors. Its descendants run to books, films, TV shows, to many gallery and museum exhibitions1. For artists and curators the appeal of Invisible Cities is obvious. Many exhibitions are composed of disparate variations on a theme, often with no explicit connection between artists save some facet of an idea they all once touched upon. We cannot go back in time and discuss space and light with Caspar David Friedrich, but through art we can create a one-sided conversation and let imagination do the rest. Artists have tried to capture some essential element of Invisible Cities in videos, paintings, installations, and even View-Master reels2.

Vladmasters by the Portland, Oregon-based artist who calls herself Vladimir, take Calvino’s stories and, in a way, crawls inside them. Instead she assembled household objects and other items to peek into what each story might look like, creating tableaux reminiscent of the Quay Brothers and Giorgio DeChirico, rendered doubly intimate by their size and the concentration invoked by looking at them through the viewer. She created a set of disks illustrating four of the cities, Zirma, Valdrada, Baucis, and Argia, one city per disk, as one of her earliest experiments in making View-Masters. After first considering them only as visual art, she built a performance work around them, handing out disks and viewers to the audience and inviting them to watch as audio accompaniment—narration, sound effects, and music, with a chime to signal when to change picture or disk—completed the experience. Without the accompaniment, or at least reading the stories to yourself as you look, Vladmasters must be a hermetic experience, akin to Polo’s attempts in Invisible Cities to describe what he has seen. You can hear an interview with Vladimir by calling the Walker Art Center’s Art on Call line.

Christopher Cerrone’s opera Invisible Cities, staged in L.A.’s Union Station by the contemporary opera group The Industry and LA Dance Project during October and November, 2013 is one of the most recent adaptations of the book. A railroad station, however beautiful, is rarely considered as a destination, but a point along the way; Calvino’s cities, while they are stages leading to the Khan’s palace, are themselves stages in a procession towards . . . what? Cerrone’s opera was disassembled, in that the performers were at various places throughout the station, and the orchestra in an adjacent building. The audience listened to the whole through headphones, at one remove from direct experience, yet not so distant as watching a screen or reading a book. They became travelers in retrospect, hearing together elements that in firsthand experience would have to be experienced piecemeal. The view to casual travelers, unaware of the work going on around them, was one of being allowed a peek into fantasy, or an elaborate and lengthy flash mob; an already historic building removed one step more from contemporary life.

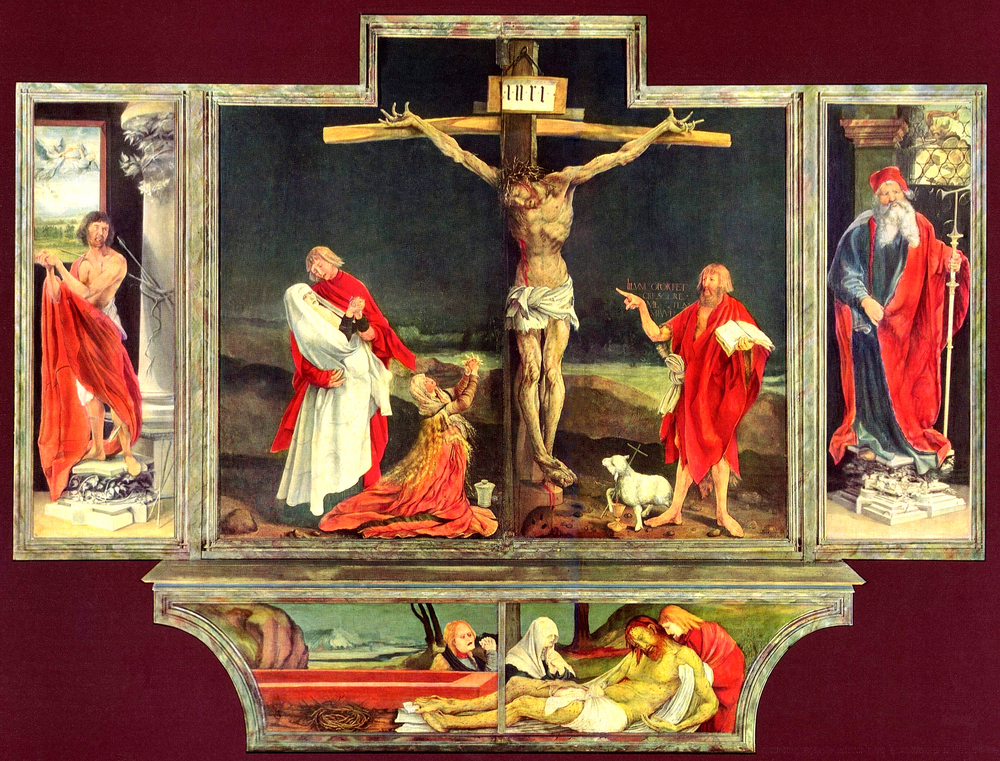

We have always arranged our vistas to suit our memories and imagination. Fra Carnavale’s The Ideal City (circa 1480s, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore) presents a pastiche of Italian architecture to define a well-structured society, and the government that must underlie that society. When Thomas Cole painted Kaaterskill Falls (1826, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford) he omitted the hotel that had been built there two years before and added a Native American, whose presence in the area was a thing of the past. Landscape painting and photography have often fallen prey to the desire to produce some degree of perfection, altering the natural to be closer to the pictorial, invisible forests and deserts that lose something in the quest for an Ideal. Eliot Porter’s mixed reputation today stems from that quest for the perfect picture, and the avalanche of picture-perfect yet artificial landscapes that fill calendars sold by environmental groups intent on preserving the real thing. Calvino had the sense to make his cities flawed. In some cases the flaws are what make them interesting, just as forests and cities sometimes benefit from their imperfections. Contemporary photographers such as Richard Misrach and Edward Burtynsky have worked in the opposite direction, finding their inspiration in damage and desolation, though that runs the risk of the "perfect" ruin. Unlike Fra Carnavale’s cityscape, people are present in their dystopias, but, especially in Burtynsky’s work, are likely to be victims of the world they have made. Let’s hope no one ever finds a way to Photoshop the human soul.

Fantastic works of architecture, such as those by Claude Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806) and Lebbeus Woods (1940-2012), now bring Calvino’s catalog (as Invisible Cities is sometimes called) to mind, even when, as in Ledoux’s case, they predate the book. Woods wrote and drew his own Calvino-esque city, in his Centricity series (late 1980s), though he rightly cited precedents in Jorge Luis Borges and Edgar Allan Poe as well. But Woods was a forward-thinking visionary, his radical designs suggesting the future rather than some alternate present. Calvino straddled time, presenting cities that were both of Marco Polo’s day and our own, as fantasies are wont to do.

The episodic quest is a form that pervades storytelling, from comic strips and manga, TV shows, to serial fiction. The Oz books by L. Frank Baum and his successors are classic examples, stories in which every few chapters brings a new land with its own distinctive people and behaviors, yet all contained within Oz (or mostly) as all of Marco Polo’s cities hearken back to Venice, his home. Whether it’s Dorothy and her companions meeting the folk of Dunkiton—donkeys, of course—and, shortly after, meeting the Scoodlers, who fight by removing their heads and throwing them (from The Road to Oz, by Baum, 1909), Oz is a succession of odd peoples and places, which are as like as not to divert from the overarching plot than contribute to it. The Oz books written by Ruth Plumly Thompson, who succeeded Baum on his death in 1919, are even more episodic. Communication becomes a challenge as characters reveal their own peculiarities and intentions. Calvino’s fantasyland subsumes motive; the explorer’s search for knowledge and the Khan’s quest for power are subsidiary at best.

Kino’s Journey, a series of light (young adult) novels (originally Kino no Tabi, or The Beautiful World 2000-present) by Keiichi Sigsawa, and an anime series, shares a basic structure with Invisible Cities. The enigmatic traveler Kino, whose backstory and even gender are obscure at first, visits different lands on her talking motorcycle (?), Hermes. Each country they stop at—never more than three days in each—has a story to tell, an idea that guides its existence. Kino learns that particular quirk or theme, survives it with as little harm to her scruples as possible, and moves on. She is Polo in motion, an Oz traveler in a more stable, naturalistic environment, yet still removed from reality. The show is intended for a young adult audience, and sometimes talks down to its target demographic at that, but it does provide food for thought.

Elizabeth Hardwick, in her book Sleepless Nights (1979), wrote, ". . . when you travel the first discovery is that you do not exist," which highlights the difference between Invisible Cities and many of the examples I’ve cited here. Books and TV shows are character-driven, and drive the plot through the protagonists. Calvino keeps his distance from that; although the dialogues between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan are central to the book, they are told in the third person, at times guessing as to their thoughts. Further, the chapters that recount the cities are sometimes told in the first person, sometimes the second or third. The identity of people, places, and even the author becomes in doubt, just some of the unanswered questions that Calvino implies without explicitly answering.

Imaginary cities can extend to nations and landscapes purely of the imagination; a world to put the cities in. Artist Jerry Gretzinger has been mapping the cities of his imagination, building and rebuilding a world in map form. The work as it stands constitutes over 2600 sheets of paper, executed from 1963-83, and 2003-present, but that does not encompass the development and growth of his creation3. "The Map tends to reflect the way cities actually grow—at least Western ones," Gretzinger wrote. "I don’t really know much about the people . . . other than to say that they speak different languages according to the parish in which they live—English, Japanese, Spanish, Italian, French, and a language unique to the Map."4

Choice and chance have shaped Gretzinger’s cities, with names such as Ukrainia, Wybourne, and Fields West. Using a customized deck of cards, Gretzinger selects a task for the day’s work: perhaps adding to a city here, or removing sections of an already completed sheet by creating a white space, called a Void, to be rebuilt bit by bit with new material. "It can obliterate areas of the Map and transport the inhabitants of that area to another dimension."5 Paint is his dominant medium, though sometimes he collages bits cut from magazines, or invites another artist to contribute. Each panel, upon completion, is photocopied in color, the color copy being the ground on which the next iteration of that particular territory will be built. So he maps not only space, but also the growth and development of successive generations.6 His is a map of time as well as place, a link between Calvino and "God games" such as Civilization or SimCity.7

A place is never one thing, but stratum upon stratum, geographical, sociological, and more. Rebecca Solnit, in her books Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas (University of California Press, 2010) and Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas (with Rebecca Snedeker, University of California Press, 2013) peels apart layers to reveal the changing face of two of the USA’s most fascinating places. Like flipping backward through Gretzinger’s map pages, past and present can be placed side-by-side, revealing their interconnectedness, their ". . . moods, states of grace, elegies . . ." in Kublai Khan’s words. Every map is doomed to obsolescence, save to the historian, when it becomes most valuable after the world it once depicted has changed. Perhaps that is something art does: saving the present until it is past. Art becomes a map of a lost world, a treasure map that we cannot follow, but only observe.

What is it that draws us to Invisible Cities more than any other Calvino book? It doesn’t have a plot; indeed, the conversations are as imaginary as the cities, as Polo and the Great Khan do not share a language and must guess or assume each other’s input. None of that matters. The suspension of reality is complete. Though Polo is also describing Venice, he is also seeing Venice through each new city, as every traveler sees new places in relation to their starting point, then vice versa. Most fantasy is earthbound; a writer makes rules and adheres to them. Where true fantasy exists the rules are erased, and imagined conversations bear equal weight with non-existent cities. Too many fantasy stories are adventure tales with fantasy spread on top like frosting; true fantasy can exist between two men sitting in a garden, perhaps saying nothing at all. So long as we dream there will be cities of the imagination for us to explore. They need not make sense, or be exactly explainable; Calvino reveals that, because Marco Polo and Kublai Khan do not share a language, communication between them is difficult, and the dialogues they share are imaginary, though who imagines what is left up to us, the reader. The artist does the same. We’re all travelers in someone’s imagination, our own or another’s. "They walk as purposefully as if they did not live in an imaginary city," wrote Angela Carter in her story "The Kiss."8 Isn’t that how we all walk?

- Jerry Gretzinger, Jerry’s Map, [installation view] (1963-present) mixed media on paper. Courtesy of the artist.

- Attributed to Fra Carnavale, The Ideal City (1480-84), oil and tempera on panel. Collection of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD

- Vladimir, Vladmaster reels, Zirma (2003), photographs in cardboard housing. Courtesy of the artist.

- Vladimir, Image from Zirma Vladmaster reel (2003), photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

[1] I tried my own Invisible City on my blog

[2] http://www.vladmaster.com/sets/?set=calvino

[3] He blogs about the work at http://jerrysmap.blogspot.co.uk

[4] Jerry Gretzinger, from an email to the author, November 19, 2013

[5] Ibid.

[6] A selection of panels currently fills the East Gallery at the Brattleboro Museum and Arts Center, Brattleboro, VT, until March 8, 2014

[7] An interactive version of the map can be found here: http://www.grinsdesign.com/jerrymap/

[8] Included in Saints and Strangers, Viking Penguin, New York, 1986.