In a recent article in The Brooklyn Rail, Chloe Wyma argues against what she sees as the commodification of feminism through the institutionalization of key artworks like Kara Walker’s A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014) and Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1979). Her analysis of Walker’s piece, in a rehearsal of countless Marxist feminist critiques, is intensely unsympathetic:

"’A Subtlety’—Kara Walker’s deliberately unsubtle, behemoth public sculpture of a hyper-sexed, steatopygous sphinx rendered in sugar—rivaled the Whitney’s bellicose Jeff Koons retrospective as a bonafide media event. While it is tempting to celebrate these developments as evidence of women’s increased visibility in the art world, this discourse of underrepresentation and inclusion is misleading."

Her conclusion, by way of quotations by Amelia Jones that are strangely left without citation, is that "branded feminism," a not-so-subtle code word for popular feminism, is a thorn in the side of the movement that thrives on collusions with the patriarchal hegemony.

While Wyma’s conclusions are certainly well-taken, her analysis nevertheless points to a problem that many other feminist writers of my generation mirror in their conceptions of identity politics. Feminist works that appeal to a large audience become lumped under a sort of "Wal-Mart feminism," and anyone who dares to shop there becomes immediately unenlightened and ignorant. What many millennial feminists forget is that, by virtue of our birth, we cannot understand that many people in the United States do not have access to feminist discourse in the same way that we do. In this vein, Wyma falls prey to a crucial critical blind spot, "The Elizabeth A. Sackler Center opened on the fourth floor of the Brooklyn Museum, permanently enshrining Judy Chicago’s once-polarizing feminist monument, 'The Dinner Party' (1979)." While it is true that The Dinner Party has become an established component of art history, what Wyma forgets is that Chicago’s work was without a home for many years. When it was proposed that the piece reside at the University of the District of Columbia in 1990, The Dinner Party became ensnared in a debate of funding and respectability similar to that faced by Robert Mapplethorpe. Now that Chicago’s magnum opus resides permanently in a museum, irrespective of one’s critiques of its particular stance, the fact remains that many thousands of people have the opportunity to learn more about feminism in a public space with an educational mission. The same phenomenon occurred with Walker’s A Subtlety. Despite the problems those of us indoctrinated in the constantly grumpy tenets of postmodernism might find, Walker created an incomparable venue for debate and introspection. The issue for many historians and critics, it seems, is that too many people got to see it; a resistance to "popular" feminism becomes nothing more than a guise for elitism.

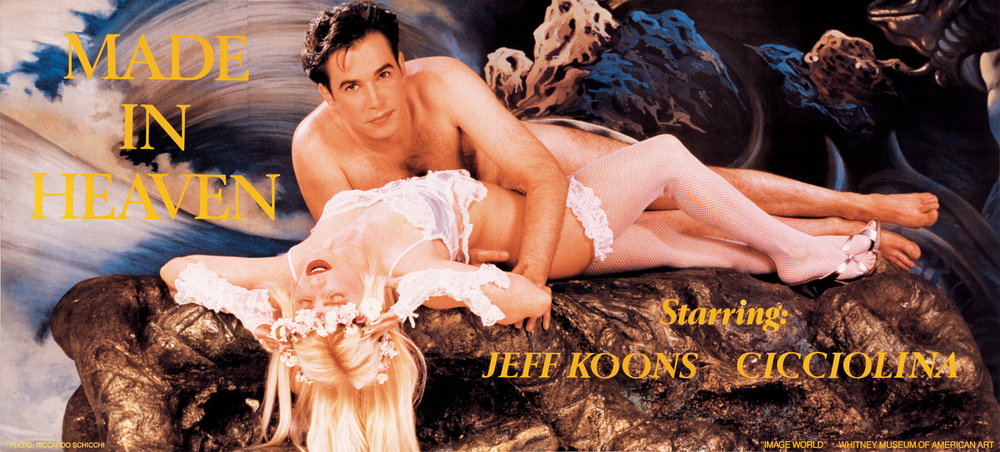

As I was thinking about these issues, I realized that an important critical lens with which to debate them could come from an unexpected source—Jeff Koons’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Whether one finds him visionary or repugnant, he is unavoidable, and his influence, for better or worse, has touched upon numerous aspects of art historical discourse and identity politics. One aspect of Koons’s persona that has yet to be discussed is his co-opting of second-wave feminist rhetoric, which, perhaps paradoxically, offers insight into the debates I have outlined.

At a recent lecture for the Public Art Fund Talks at the New School, Koons alluded frequently to what has been called "essentialist feminism," a conversation that sounds very different coming from a man’s mouth. He spoke at length about his sculpture of the Venus of Willendorf, a centuries-old symbol of femininity that, in its allusion to "primitive" sexuality, represents for many a time wherein sex differences were cause for celebration. Koons has said of his Balloon Venus (Magenta): "The Venus of Willendorf is truly a symbol of fertility because it can procreate on its own. The Venus’s breasts are full, they’re voluptuous, her stomach, a real symbol of fertility. But if you look and you let your mind start to go, you realize that the breasts could actually be testicles and that the stomach could actually be a phallus and that it’s actually going in on itself, and procreating." Koons’s sculpture thus becomes representative of biological determinism, an oscillating process of one to the other, one set of genitals to another set of genitals—in sum, a reaffirmation of the fixedness of gender and biological determinism. Koons revels in these visions of womanhood, but so does second-wave feminism. What makes them different, besides the passage of time? Perhaps it is in their similarity that we can find a call to action. Surely Koons’s feminisms should not ruin our understanding of second-wave-inspired thought as a whole.

Jeff Koons, Moon (Light Pink), 1995—2000. Mirror-polished stainless steel with transparent color coating 130 x 130 x 40 in. Collection of the artist. © Jeff Koons.

Koons, like his feminist "predecessors," also loves his crevices, curves, and wombs as formal devices for an enlightened, "prehistoric" sexuality. There is, of course, no such thing as a sexuality that transcends discourse, according to the postmodern reformulations of gender theory in the 1980s and 1990s. What the second-wave attempted to accomplish, however, was the creation of a specifically feminine space in a society that denies women a space for speech and representation. Judy Chicago’s desire to create a feminist formalism that drew upon female modernists like Georgia O’Keefe was not only an attack on the social institutions that would silence women artists, but also minimalist strategies that distanced themselves from the traditionally female-dominated imagery of the handmade and the decorative. Chicago’s 1964 car hoods, which predated Richard Prince’s, bring flamboyant colors and sensuous lines into the hard-edged world of Finish Fetish—a seemingly paradoxical combination on which Koons has certainly drawn. Moreover, one can certainly see a connection between Koons’s Moon (Light Pink) (1995-2000) and the explosion of pink exhibited by Lily van der Stokker at Koenig and Clinton Gallery in New York City this month. One can draw parallels, but I cringe at the thought.

Artists like Travis Jeppesen have pointed out how absurd and sexist this rhetoric is. In his poem-installation based on the Venus of Willendorf, shown this past summer at Wilkinson Gallery in London, Jeppesen speaks ironically on behalf of the famed statuette: "Grazing on contradictions, I am skin without organs, worth more than diamonds, and yet nothing—female without sheen. The first phallus and the last to bleed. Touch without tactility." To say that Koons’s relationship to feminism and race is tenuous is old hat at this point. What is important to understand why exactly Koons sounds so ridiculous. It is a product, I argue, of the forced patina placed retroactively on feminism by millennial art writers. Though the ideology sounds incredibly antiquated, the celebration of femininity as a separately embodied state of being was a revolutionary strategy pioneered by feminists in the 1960s and 1970s. It represented a necessary step for postmodern feminism; if a discursive space for women had not been created, there would have been no room for subsequent critiques of gender. Unfortunately and perhaps unsurprisingly, Koons latches onto the most problematic aspects of second-wave female-centrism—the mother-goddess and the connected concept of the pre-industrial matriarchy. He plays into and capitalizes upon prejudices surrounding feminism that are mainstream in the academic/artistic complex by producing a ludicrous performance that makes fun of female centrism and feminist formalism. Irrespective of one’s opinion on Koons’s art, his presence necessitates a new understanding of the biases that we hold against prior feminisms. If it is so easy for a male artist to coopt feminist strategies exactly because they sound outmoded, there is certainly a need to consider how such a takeover could occur. We cannot move forward with new feminist and queer understandings of the world if those that form the basis of contemporary politics have yet to be fully resolved.