On opening day of the 2013 TransCultural Exchange Conference on International Opportunities in the Arts, a green laser beam shot across the dark expanse between Boston University's School of Law and the newer Student Village skyscraper. Florian Dombois, the German artist behind uboc No. 1 & stuVi2, is also one of the founders of the Journal for Artistic Research (JAR). The laser remained lit for the four days of the Conference, drawing a simple and elegant line across one of Boston's busiest thoroughfares.

Stephanie Cardon Though I wasn't at your talk at MIT in 2012, when Ute Meta Bauer organized a lecture series on Artistic Research, I did attend many of the presentations. I saw Attila Csörgö, Guillermo Faivovich and Nicolás Goldberg for example, and later Laurent Grasso. In fact, it was evident that when we talk about art and research, there are really many different applications of the approach.

Florian Dombois There are, and I must say that meanwhile, for me, I feel like it has run its course. For me it was partly a game, partly serious. "Artistic Research" is a borrowed terminology, and in that sense it can never really solve the problem, it can only address certain difficulties. Meanwhile it has become more common, and people are using the term in a way that is causing me to want to back away.

SC Artistic Research now has a presence in the academy; there are formalized approaches that have come into existence, as courses, such as the one at MIT, but elsewhere too.

FD And the last Documenta too was addressing the topic, more or less.

SC So let's talk about uboc No. 1 & stuVi2, the piece you created here, under the auspices of TransCultural Exchange. I'd like to hear from you how it came about technologically, aesthetically, logistically, and conceptually, of course! What led to the selection of the two buildings? What were you hoping to make manifest through their interconnection?

FD In 2011, I did a similar piece called Szkieletor and Błękitek in Krakow, and Mary Sherman saw it there. It was part of Artboom, a city-wide festival, for which Jenny Holzer, Pavel Büchler, and I were invited to create pieces. We could pick almost any site. I chose two buildings that were former office blocks outside the old city. Szkieletor is a famous ruin. It's a skyscraper that was built in the '70s and was never finished. Since then it has guards watching it 24/7: it may be the most famous building of Eastern Europe. Błękitek, the second building, the city had been hesitating to break down. It's also from the '70s and both buildings represent a communist departure from old Krakow and its royalist past. It was turned into a bank after 1989. Krakow also happens to have a story about towers that inspired me: Saint Mary's, the main church, has two steeples of different heights, and the tale goes that there were two brothers building these towers and when the older brother realized the younger one's tower might be taller than his, he killed him.

SC A Cain and Abel story.

FD Totally. So that was the starting point. When Mary asked me here, it was clear that I had to choose two skyscrapers. There was some discussion with the Prudential Building and the Hancock Building, but that seemed very obvious. I saw a better fit with Boston University, the hosting site of TransCultural Exchange. For one reason, my personal interest currently is in the '68 generation and how we, the next generation, can get rid of them.

SC [Laughs] They've overstayed their welcome?

FD I've really had enough of it. They've been around for almost 50 years. It's so totally boring. One of the two towers I chose on the BU campus was done by Josep Lluís Sert [1902-1989], the brutalist architect. It's a beautiful building, even if it shows its age. The other tower, the Student Village, is only ten years old. It has no particular architect and was designed by a company, but if you look closely it's mirroring the style of Sert's building. There's a kind of father-son story going on here, which I found interesting to explore. One's a concrete structure, the other a metal structure. So on and so on. From the beginning, another reason for choosing the site lay in the fact that the space between these two buildings bridges the junction of all kinds of traffic. Pedestrians, cars, public transportation, highways, airplanes, ships. Because TransCultural Exchange brings all kinds of artists from all over the world, it made sense to highlight the junction as a metaphor.

I see the "Talking Towers", as I call them, as a kind of series, though the title is always specific to the site and is taken from after the buildings' names. BU students refer to the Student Village building as "StuVi." Here I also shortened the nickname for Sert's building, "the ugliest building on campus," to uboc, which I think is an improvement. But I didn't pick it because I agree it's the ugliest building. I don't.

SC You connected them to each other visually with a green laser beam. But the beam is also there to measure movement?

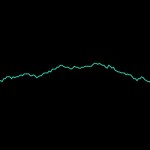

FD The green laser beam marks the connection and a distance visually, and a range meter measures the sway of the buildings and the changing distance between them. Opening day of the conference a webpage goes live on the TransCultural Exchange website: on it you see the sway of the buildings measured on a graph as a waveform, in real time.

The X-Y axis doesn't include any numbers. It doesn't matter to me that the sway is one millimeter or five. For me, the pleasure comes in watching the line. It has a poetic quality. It's not that I mind numbers, but here the beauty lies in the line being drawn. This line gives insight into what's going on on a macro level: it shows traffic, it responds to earthquake waves traveling around the globe. It's a very simple intervention. But it grows into the body of the earth. These two buildings are like needles probing the globe. It leaves a lot to the imagination. I love works that combine something physical, that possess aesthetics to engage with, but that also contain a conceptual part which grows and that you can take with you. In a sense, that's what makes the work viral.

SC Tangible, but abstract enough that we can take it with us as we move though the world. For uboc No. 1 & stuVi2 is the data being collected and stored? Did you consider creating an app to gather the data, or does it exist and function only as an html page?

FD There's a live transmission from the range finder to a web server. A program reads the incoming data and visualizes it. I thought about creating an app, but using one means signing up with Apple, and really I can do everything I want with the software I have and an html page. I'm currently working on a project with my colleagues in Switzerland about how to put art online. There's a huge debate always about how to relate to the big players: Google, Apple, etc. Meanwhile, of course, I have an iPhone . . . but that fact doesn't always make me happy.

SC Do you ever use the collected data to create parallel, related artworks?

FD I know the art market loves artifacts. Should I do an etching of the waveform? People like Christo are very smart in the way they use documentation to feed the market, for instance. I'll save the data, for sure, but I'm not certain I'll use it.

SC I ask, because in a previous project of yours, Luginsland, you spoke about how the seismometer creates a drawing without hesitation. And the outcome of the project was a series of drawings created by the machine.

FD In that particular case at the Kunsthalle Bern, the seismometer was part of the installation, and the premise of the exhibition was that of a machine producing a drawing over the course of seven weeks. The drawing finished with the end of the show. Two years later I had an exhibition at Berlin's gelbe MUSIK, a gallery that specializes in visual art / music correlations—an approach which comes out of Fluxus. There it made sense to show these graphs, and I made recordings, using the drawings as musical scores. We had a very interesting discussion around the question of what makes a musical score, who is the composer and who is the interpreter. In that context it made sense to play on the artifacts.

SC Yet a relationship to sound seems present to me in uboc No. 1 & stuVi2, even if it is beyond the realm of hearing and exists on a global, macro scale.

FD I'm not a musician, but sound seems to me like a very interesting escape route from '68 and modernism because it's a neglected area. It's an attitude of looking at the world. I'm happy being between the visual and sound worlds. I've been working with sound for fifteen or twenty years now and it totally influences my understanding of an artwork: the temporal piece is obvious, waves coming and going, starting and ending. The question of composing things is more and more present in my work. A few weeks ago I was speaking with a photographer. I don't understand why everyone compares photography to painting, other than the relationship to the frame. It might be more fruitful to think of its relationship to sound and music: the negative being a score and the print an interpretation. Working with sound has changed me. uboc No. 1 & stuVi2 is an acoustic piece too, even though you cannot hear it. Sound is definitely relevant. It seems to always come up intentionally or unintentionally in what I do.

I had a show ten years ago at Galerie Rachel Haferkamp, a gallery in Köln dedicated to sound art and run by Hanjo Scharfenberg. Maija Julius, daughter of Rolf Julius [1939-2011], the renowned German sound artist, gave an introduction. She asked me about the ten pieces in the show: half made noise and the other half didn't. I felt the ones that didn't were still clearly acoustic because of the context. A few of them were playing with room acoustics; those were passive sound works, you could say. One piece imagined what would result from an earthquake: it identified the places of danger and mapped the threat within the room. An earthquake is such a strong acoustic event, that playing the sounds would be too Hollywood. You don't need to do that to evoke the magnitude of the event.

SC You studied geophysics. Does your interest in earthquakes have less to do with the physical event and our association to disaster, and more to do with the physics of sound?

FD I've studied and worked on the idea of how an earthquake impacts society, but on an artistic level I'm very interested in the fact that everything is unstable, that we are in fact standing on fluid. How these things modulate through time fascinates me. I grew up with the arts and I decided not to study them because I knew from experience that I wouldn't be able to study much of the things I was very interested in if I studied art. Especially in Germany, you have an education system that doesn't allow for that kind of cross-disciplinary approach. I never studied geophysics with the intention of becoming a geophysicist, I did it to understand and to enlighten my imagination.

If you were to ask someone on the street where the unknown is they would point to the sky. That's not true. The unknown is one meter beneath us. The deepest hole is ten kilometers deep, but the real body of the Earth is closer to thirteen thousand kilometers. It's a huge space we are close to and haven't explored.

SC You seem drawn to the fictions of that too.

FD Yeah, for sure! I think that's why I'm an artist. People often misunderstand me because they see me using instruments and they assume I'm interested in the factual aspects of the research. Science is so fictional anyway, there is a huge space for stories, and that's particularly interesting for art. Physics and natural science are so present, it's stupid for artists not to study and understand it at least a little.

SC Are you still involved with the Journal for Artistic Research?

FD Not anymore, I stepped down from the board in March this year. I know the people involved—they're doing a great job—but I'm pretty much out. Art as research for me started over ten years ago. It clearly has to do with my past in science and the parallels I see between the two worlds. But the hijacking of the terminology seems to spoil both sides. In the beginning, the combination was really intense. People screamed. Now it doesn't feel as fundamental.

SC When everyone is nodding at you in the audience and applauding, it's not good anymore.

FD Yes, then something's failed. We've lost the energy. At the moment I'm trying to name the two approaches I see in my work: I'm calling them portraits and landscapes. This whole Artistic Research debate—I always called it Art as Research, which I think is a major difference—fits into the landscape work. Whereas uboc No. 1 & stuVi2 I would call a portrait. Here we see two clear artifacts. The objects I've made are portraits. The processes involved in art as research, all of the work around sonification, creates a landscape.

SC Let's talk a little more about the portrait here in Boston, then, and go back to what you said about debunking '68, a son standing up to his father.

FD We could fill another hour with that!

SC From my perspective, growing up in France, the soixante-huitards ['68ers] manifest a certain scorn for the next generation and its lack of political and social engagement.

FD That's the first thing they don't realize. The only way to oppose them was to avoid giving them a simple counter-argument. How do they fight a generation that tolerates them? The fact that we don't stand up makes them mad. But that's sad because ultimately it's really a trap for us. We forgot to develop an Oedipus complex. We forgot to kill our fathers. It may be a little late, but now I'm ready to develop slogans. Actually, I'm working on a manifesto.

There are certain aspects about the buildings which I cannot control but which end up affecting the project in a really nice way. For instance, because the School of Law is concrete, and the Student Village is primarily metal, the concrete structure doesn't move, but the newer building sways. In fact the new building does most of the swaying, so when we talk about '68 and us, a younger generation, it fits. I don't particularly like the stuVi building. Architecturally it is pretty boring. But when we think of the generational question it becomes a really interesting analogy: like the tendencies of the generation that followed '68, it doesn't make a clear statement, it picks up certain architectural elements from the brutalist building without developing it into something of its own. The whole structure mirrors Sert's building, but functionally the parts that mimic it only serve to hide the air conditioning and so forth. The generation that created Brutalism was unhesitant, very black and white, partly because it was responding to a very problematic history, especially in Germany. We, the younger generation, are always approaching things with shades of grey. We need to be clearer about what we mean, without recreating such strong good/bad or A/B thought processes. We need to take more risks. The '68 generation didn't hesitate.

SC What you pointed out about the School of Law being a statement building by one architect versus Student Village being designed by a company is very telling. There's a dilution of the individual identity, and therefore its reason for being perhaps isn't as clear.

FD The movement of the two buildings has a lot to do with how we relate to each other. We try to come closer but we cannot. The laser is a light impulse that is reflected. So there is an attempt to reach out and communicate, but the gesture is also full of melancholy because of the fact we cannot reach each other.

SC It's like a dance.

FD Thank you. You know the film Man on Wire? I find Philippe Petit's project of walking between the Twin Towers so dramatically beautiful: there was a point half way between the towers where he lay down on the wire, and no one could reach him. Expressing and externalizing this kind of melancholy is the point where I start.

- Florian Dombois uboc No. 1 & stuVi2 , Boston, 2013 Photo courtesy of the artist

- Florian Dombois uboc No. 1 & stuVi2 , Boston, 2013 Photo courtesy of the artist

- Florian Dombois uboc No. 1 & stuVi2 , Boston, 2013 Photo courtesy of the artist

- Florian Dombois uboc No. 1 & stuVi2 , Boston, 2013 Photo courtesy of the artist

- Florian Dombois uboc No. 1 & stuVi2 , Boston, 2013 Screenshot of the html page

This interview was conducted during the TransCultural Exchange's 2013 Conference on International Opportunities in the Arts.

Big Red & Shiny was a media sponsor for the 2013 Conference on

International Opportunities in the Arts presented by TransCultural

Exchange.