Looking at Will Cotton’s paintings remind me of cartoons; or one cartoon in particular. The Fleischer Studios Color Classic cartoon Somewhere In Dreamland (1936) is the epitome of Depression-era wish fulfillment. Two innocent, almost overly cute children are caught in dire poverty. Their mother is barely able to feed them; there appears to be no father. The children drop off to sleep after an inadequate meal and dream of a wondrous land of candy, everything they might want to eat growing right out of the ground for the taking. It’s not subtle, and succeeds largely through the wistfulness of the title song (by Murray Mencher and Charles Newman) and the Fleischer brothers’ innovative use of live-action settings overlaid with animated characters. There’s a happy ending, of course.

Dreamland never went away. It reappears regularly these days in Will Cotton’s paintings and sculpture. Cotton makes sweets—real or ersatz—and decks his models in them, or swirls cotton candy into clouds and discreet bits of drapery. Discretion is his watchword; nothing either challenges or offends, as clean and bland as what adults imagine childhood dreams to be. At times, the models are excluded, and Cotton fills paintings with food, or builds sculptures of precariously stacked cakes.

Like later Fleischer cartoons—meaning those made after the imposition of the Motion Picture Production Code, in 1934—this is almost too much. Beyond a certain point sweetness causes nausea; there’s no accident in the double meaning of the word "saccharine." Will Cotton has made a career out of his fixation on candy and baked goods, but it’s a double-edged sword. Sugary things have long been known to be just empty calories, and a quick look through Cotton’s work gives the same impression. He labored a great deal to bring forth something so stale.

Cotton turned photographer this year, shooting the actress Elle Fanning in various outfits—many augmented by Cotton’s candies—for New York magazine’s Spring 2013 Fashion issue. This called for an extra dollop of discretion, as Cotton often paints his women naked or near-naked, which hardly works for a fashion shoot; Ms. Fanning’s tender age (fourteen years old when the photos were taken) was another reason. Looking at these photos and how they succeed when so many of Cotton’s paintings don’t, got me thinking.

Why are Cotton’s naked women so unerotic? The Fleischer’s most famous animated character, Betty Boop, was far sexier while being much less realistic. Fantasy is a part of eroticism, but Cotton’s fantasies are off-the-shelf, banal. They lack personality, which Betty Boop had aplenty. It isn’t enough to just take your clothes off. Art historians have divided the idea of a state of being undressed into naked and nude. Prominent definitions have come from Sir Kenneth Clark, who devoted a whole book to it (The Nude, a study in ideal form, 1956); Robert Graves, who did it in a poem (The Naked and the Nude, 1957); and John Berger, who did it on television (Ways of Seeing, 1972). I would say Berger defined it best, and I’ll follow his example: Naked is to be one’s self; simply a state of openness, usually involving physical exposure. Nudity is a conceptual device, through which nakedness is given a place in a dialogue. Nakedness simply is; nudity is addressed to someone. The assumption that all nakedness has sexual connotations is mistaken. This is where Will Cotton fails. His women—so far as I know he has never painted a man, nude or clothed—are self-involved. That does not preclude sexuality, even if only a voyeuristic kind, but, aside from the fact of their nakedness, nothing is suggested.

One of the most recent works to take up the naked/nude dichotomy is Frances Borzello’s book The Naked Nude (Thames & Hudson, 2012), which proceeds along the spurious notion that nudes did not become daring or transgressive until recent decades. There have been "safe" nudes as long as there have been "unsafe" ones, and I won’t stop here to define the two. What’s wrong with Will Cotton’s nudes is not that they are safe, but that they are unimaginative. There’s nothing wrong with appreciating a beautiful woman as something more than a sex object; some outstanding works of art do just that. But grown women seem incongruous in Cotton’s lurid pink settings. They should be flattered—Cotton’s women are always shown to advantage—but it all rings hollow. Considering the obsession with body image in today’s society, you might imagine them to be slightly embarrassed by all this confectionary around (and sometimes on) them. But no, they’re not embarrassed because they’re not really being seen, they’re not really there. This is Will Cotton’s dreamland, and his thoughts are the only ones around. As Cotton himself said in an interview, "It’s a utopia where all desire is fulfilled all the time, meaning ultimately that there can be no desire, as there is no desire without lack."1 Can one be nude, as I have defined it, without desire? Take away desire, and what’s left?

Cotton was a good match with singer Katy Perry, whose 2010 album Teenage Dream featured his artwork, including his art direction on the music video for her song California Gurls. Perry’s face and hair are a little too carefully made up, her expressions too precise to have any naturalness—again, I think of Somewhere In Dreamland. Many of Cotton’s nudes are that way, becoming mere props instead of individuals. When Art News magazine splashed Cotton Candy Katy (2010) on its cover with the headline "The Shock of the Nude" (December 2010), the effect was almost comical.

You’re safe with Will Cotton, and so is your daughter. There is nothing remotely pathological in his approach to the nude, neither predator nor voyeur. He’s the last artist anyone would suspect of having fondant-frosted body parts in his refrigerator. He stays within the tenets of European classical eroticism—no body hair, no pudenda, a nipple or two mostly because they can hardly be avoided. Like Maxfield Parrish’s paintings of women on rocks, they are tasteful almost to the point of invisibility. Cotton’s kind of quaintly pre-feminist imagery is found in few places these days—few places, that is, with which he might want to be associated. And glorifying food has the same vaguely illicit appeal as glorifying the female body.

To divine Cotton’s antecedents, look back to old masters: the Hudson River School, Tiepolo, perhaps (Consuming Folly, 2009-10 reminds me of something painted on a ceiling somewhere), or more recent ones such as the pin-up posters I mentioned earlier. I would look back to William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) the once admired, now widely loathed French academic painter. Bouguereau represents everything the Impressionists and successive decades of artists worked to oppose: nakedness without nudity, a deep gulf between the work and any element of present-day life. Bouguereau’s people are just a bit generic—they are gods and magical beings out of mythology, after all—and they rarely engage the viewer. With Bouguereau and Cotton, nothing is said or expressed. There isn’t even any irony, as is found in Cotton’s contemporary, John Currin.

Let’s stay with Currin for a moment. Like Cotton, he has a great amount of technical skill; also like Cotton, there has too often been little content behind that skill. Where Currin draws visual inspiration from Mannerism, Cotton seems to draw from the world of commerce. Actually, in the latter case it’s the other way around; the advertising world has begun openly borrowing from Cotton, as this is easy to do without irony or any necessary alteration. Neither the artists nor the advertisers have much to say, though they have the ability to be eloquent and (in Currin’s case) even a bit snarky saying it. Both painters, like Bouguereau, have trouble with faces: Currin moves too often toward caricature; Cotton to slightly soft focus banality, a hazard when painting models (Ice Cream Dona II, from 2011, captures this perfectly). What Elle Fanning gave Will Cotton was a face he did not have to recreate, to the point where just her simple presence threatens to overshadow both clothes and setting. Still, if you’re going to be upstaged, it’s best if you’re upstaged by a professional.

Cotton began to explore performance in 2011, staging two brief ballets on the themes of whipped cream and cotton candy, under the title Cockaigne, at Performa 11 in New York. With John Zorn, Caleb Burhans (both supplying music), Charles Askey (choreography), and Pascal Gauvin (perfumer — yes, there was a designer scent) he brought his sugary world to life. Despite Cotton’s earlier statement, William Corwin, writing in the Brooklyn Rail, wrote that: ". . . they are about delving into that very old and very Freudian territory of childlike unremitting desire. " Everything was standard Cotton tropes. At less than five minutes per ballet, the work was easily overlooked. His designs for Peter and the Wolf (2012), an annual staging of the musical work as part of the Guggenheim Museum’s Works & Process performance series, showed charm and precision, and a design sense that reminded me a little of the late Maurice Sendak. There was candy aplenty, but it was in aid of a story. The missing element in his work appeared.

Will Cotton is at a crossroads in his career, his signature style in danger of being assimilated by commercial interests. He could step into that world and become an illustrator and commercial artist himself, or fight to keep his work his own; which most likely means striking out in some new direction. He has painted and sculpted cakes and candies in disarray, slumping and breaking apart. As the dark side of food—a rejoinder to Lichtenstein or Thiebaud’s cakes—these work well. Landfall and Ruin, both from 2012, are good examples; his earlier sweetscapes, such as Custard Cascade (2001) are much more tranquil. Press releases and articles on Cotton’s work have tried to paint these as dystopian, a perfect world of sweets collapsing from neglect. What they are is an apt metaphor for the way his oeuvre is crumbling. The ultimate choice will be his. Nice though it might seem, Elle Fanning cannot be expected to ride to the rescue every time.

THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

If I could fall in love with a brushstroke, I’d pick out a bouquet for John Currin. There are few prominent painters today who paint with such a growing command of the classical technique. If that were all it took to make a great artist, then Currin’s future would be ensured.

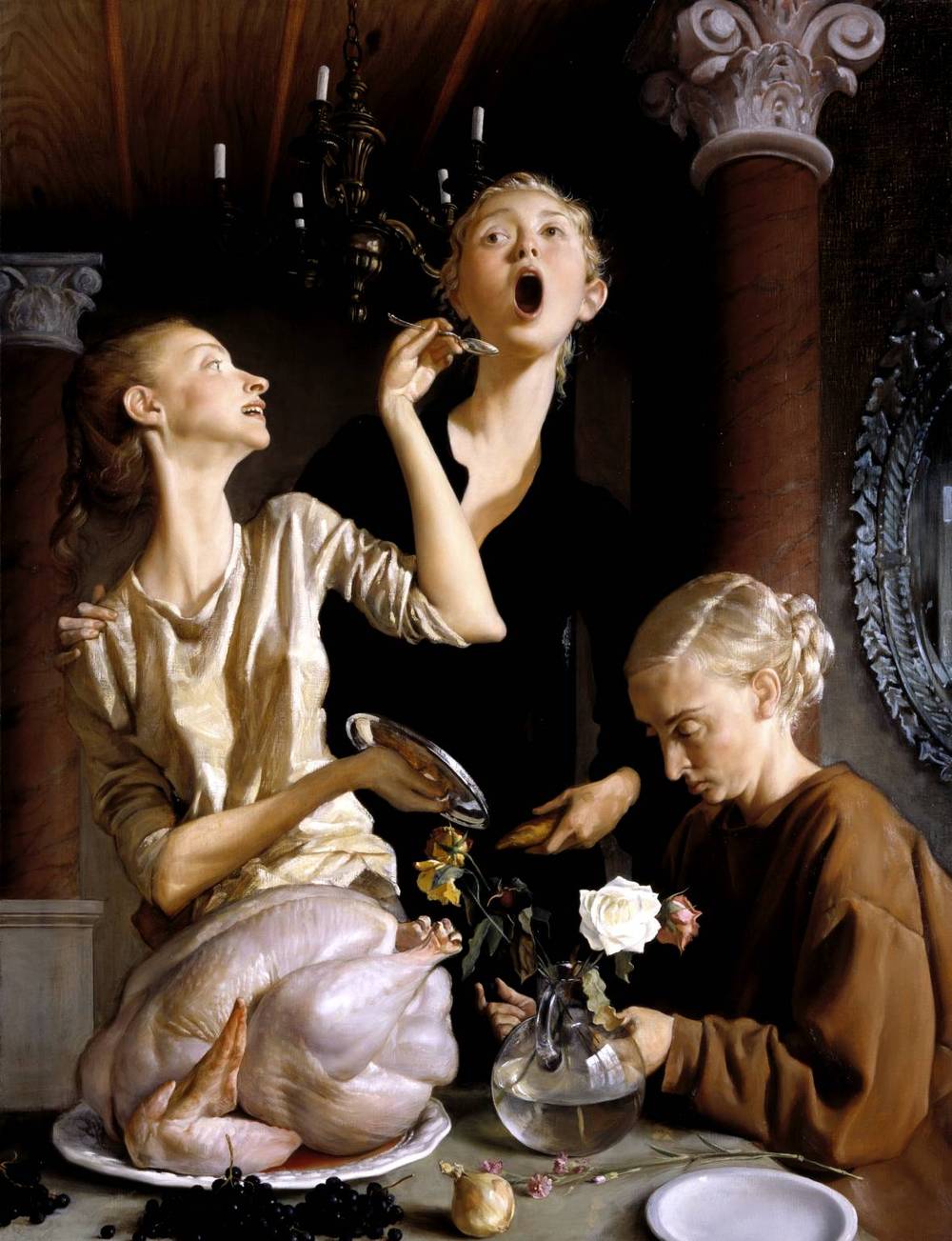

Look at Thanksgiving (2003). Three women are grouped around a table, preparing the holiday dinner. The women are very much alike, each based on Currin’s wife, the artist Rachel Feinstein. The raw turkey that sits in the lower left of the painting is a credit to Currin’s growth, as finely painted (and incongruous) as something out of Dali; only a few years before such work would have been beyond him. It’s a pleasure to see an artist who knows the classical technique and handles it with apparent ease. There are a lot of fine painters around, but so few of the best draw on art history that it almost seems subversive. Currin’s brushwork at its best is unlike the women in his paintings: graceful, intoxicating, and magnetic.

Currin draws on art history for his ideas of anatomy, and then takes them a step further. For a long time the stereotypical Currin figure was spindly-limbed with a prominent stomach, their poses not quite in classical contrapposto. Cranach is often mentioned as a source, and there are affinities to more artists like the sixteenth-century Flemish painter Marinus van Reymerswaele, or the Leipzig school painter Werner Tübke. When his figures attenuate, Currin approaches a Neo-Mannerism that transcends caricature. Neo-Mannerism is the art-historical term; the suggestion that, in those works, all of Currin’s women suffered from eating disorders casts a pall over their smiles and carefree actions. Currin’s women of this period are not sexy. Gollum would look at home with them. I mention Currin’s men only to say they aren’t worth mentioning.

His portrait of a topless Bea Arthur, from 1991, is a good early example: a mediocre likeness, the face seemingly unrelated to the body to which it is attached. The whole thing comes off as a schoolboy joke. It isn’t even well painted, and looks flat in every way save for Ms. Arthur’s bosom. In response to accusations of sexism Currin produced a series of crudely painted women with outsize breasts, a move that got him a lot of publicity but did nothing for his reputation other than put him in the same tacky/funny/angry barrel as Lisa Yuskavage. I don’t know if he regrets these works; he ought to. There is next to nothing to recommend in them.

Any sensible lover (Is there such a thing?) knows that physical beauty is the least important kind, including in paintings. Sculpture allows a little more leeway, but I’m not sure I would want to see Currin’s gangly women in three dimensions. Currin fails when he tries to move beyond the physical. His people have little soul—caricatures rarely do—and it becomes difficult, almost impossible, to arouse any interest in them. They pose like bizarre fashion models. There are examples of painted figures without personality—many Picasso nudes, or some of Cézanne’s portraits of his wife—but you have to be a genius to pull it off. Currin substitutes irony and satire for personality, which, even in the heyday of those art-world blights, was never enough.

Some targets are so easy it’s hardly worth shooting at them. Hunters might disagree, but satirists know what I mean. For all his fine trappings Currin chooses the easiest target, the foibles of the middle-class; by now even the yuppies themselves (or most of them) are in on the joke; some of them own Currins. His paintings too often boil down to beautifully appointed sitcoms, each gag telegraphed with its own laugh track, a toned-down John Kricfalusi animated cartoon with the sound muted. The grimace-inducing adjectives of TV ads—remember when shows were touted as "Quirky, zany, wacky"—apply all too well. However (and here I almost wrote "Ironically…") this irony and satire is what made Currin’s reputation. His technical skill, while enjoyable, is nothing new, and was still embryonic when he came to prominence. Art fairs are full of Old Master-influenced still lives and portraits, all so deadly serious that their solemnity turns to somnolence. A rebel with technique, now that’s something.

Though maturity seems a way off yet, change is noticeable. Currin moved away from his stylistic excesses but, in typical fashion, not in a way that inspired confidence. He then began making paintings that drew inspiration—that’s the polite assessment; "copies" is more direct—from pornographic photos made in Denmark in the 1970s. To ask, "Why?" is just the beginning. Yes, it removes the strained, stick-thin women of Currin’s past and substitutes passé hairstyles and explicit nudity. These are major changes. His skill as a copyist is confirmed; his changes to the originals are often the weakest element of the works. But the exploitative qualities of such appropriation are many. Elevating porn to the level of art is something that resurfaces every now and then; it is a pathetic, fallacious endeavor, and most of the time, stupid. Art elevates. Porn diminishes. These paintings are counterparts to Jeff Koons’ explicit sculptures of he and La Ciccolina (the Italian porn star to whom Koons was married) having sex, without the smirking complicity of Koons. What you get feels emptier than in Currin’s previous work; at least in the earlier stuff he was trying to say something about society, weak though his points were.

There is room for social satire in fine art; indeed we need it. From the gentleness of Rowlandson to Daumier’s eloquent line and rough edge to the acid bite of Grosz; there are artists who carry on this tradition, but few of first rank. Currin hasn’t found his métier yet; perhaps satire’s not really his thing. In his earlier work he needed to be cleverer or angrier. There is room for the odd, semi-Surreal touch of a Balthus or Henri Rousseau, or a warped take on Thomas Hart Benton. I think of so many other artists when looking at Currin’s work that I end up barely thinking of Currin at all. As it is, Currin is Daumier without a real feeling for social satire, producing art that is beautifully crafted but banal; his targets are unimportant in the workings of justice or the greater world. He’s like a baseball pitcher who can throw but can’t fool the batter. We see his pitches coming, and let them go. His 2003 mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art was undeserved—to continue the metaphor, he was brought up top the big leagues too soon. His work quickly became trite and repetitive. There’s a spot on the roster for him when and if he ever matures.

That’s how things stood until the last two years or so; perhaps less. Then something happened to Currin, just what is not clear. He has gone forward and back at the same time. The smart-alecky quality of his work to that point, the campiness and crassness, seems to be dropping away. In its place arose a traditional and genuine eroticism and technique that are downright old-fashioned. Those who love Currin the smartass might be dismayed, but this is a change worth noting, perhaps even worth cheering over. The distortions in his figures, already in retreat, have ebbed further. A work like Reader (2010), of a nude woman with a book, has a delicacy and calm that is so un-Currin you might walk by it and not recognize its maker. A follower of some nineteenth-century Century artist, perhaps, or a genuine work of that era, but not the bourgeois jester we had come to expect. Sometimes a joke is worked in—Good Beer (2012), with a languid woman holding a glass of beer on her thigh next to her pudenda, could be more subtle—but the execution and the overall tranquility of the work is revelatory.

An adult is emerging from the cheeky adolescent (Currin turned 50 in 2012) and the change is enough to make me pause. Perhaps he hasn’t found anything suitably modern or postmodern to slip into these paintings, but, so far, that doesn’t seem to be a drawback. The beauty of the world is worth capturing, and often the "cutting edge" doesn’t prove equal to that task. This new, mellow Currin is less exciting than the old, but he is proving his range as an artist. He has gone from a tiresome but unique artist to a promising student. I count this as a change for the better. The danger now is that he will be seen to have sold his soul for respectability, or to have done a hypocritical about-face in his views on humanity. The pivotal step is the next one, in which he brings his new skills and his old into some kind of rapprochement, becomes an all-around player. I won’t tire out the baseball metaphor much more; suffice it to say he might earn that roster spot yet, but it’s an uphill climb.

KNOW THYSELVES

At the center of Julie Heffernan’s art is a great calm. It is a calm that is not just stillness, but encompasses a certainty that reaches back into the history of art. I almost wrote "portraiture" instead of "art," but there is something about Heffernan’s paintings that is not encompassed solely by the idea of the portrait. She stands there—the majority of her work consists of standing figures, usually herself—and looks calmly out, insouciant, unruffled by whatever persona she has adopted. It is not exactly a masquerade. She has behind her the weight of the past, and can take whatever comes with impunity.

These personae, though perhaps avatars would be the more contemporary term, run to fantastic garments and lush settings. Self-portrait as Two Headed Queen (2000) presents two women, like all her figures based on herself, calmly looking out at us while a volcano throws ash into the air in the background. Her inspirations are explicit—English society portraits, Dutch and Flemish masters, Fragonard, and especially Velasquez, from whom she owes some technique and compositional elements—but well quoted. The heavy jokiness of Pop art and postmodernism is absent; if Heffernan is joking with us, it is with the aplomb of a Buster Keaton, but a Keaton somehow transplanted into the lavish settings of an MGM historical epic. At times her own body may be shrunk to child’s size, dressed out in Spanish Infanta garb made of fruit or animals or flowers (echoes of Giuseppe Arcimboldo) but these are trappings. The look on her face is the same from one painting to the next, topped by her carrot-red hair. Unlike Cindy Sherman, to whom Heffernan has been sometimes compared, Heffernan does not assume a character to go with the costume. She is often topless, but her slender body is not blatantly sexual. This is not art for the "male gaze" but it draws from traditions of portraiture that always considered the woman as object. Her fantasy worlds have more in them that just sex. She is not bared in the Will Cotton sense, nor in the Lucian Freud sense; I think those will do as polar opposites. Her reddish hair and the stillness of her poses brings to mind Sir Peter Lely’s portrait of a nude Nell Gwyn (c. 1670s), but without the sexist baggage of that work. Rather, there is something in the frank, almost bored expression on Nell Gwyn’s face that is echoed in Heffernan’s. "Don’t make such a fuss," they seem to say. "It’s only me." Whether presented as goddess (Self-Portrait Sitting on a World [2008] shows her wearing a verdant landscape like a blanket), victim or part of nature, she is always in her element, at home in her own fantasies.

After blasts of Takashi Murakami and so much ADD-addled art that surrounds us, Heffernan is a curious creature. We expect her paintings to be so much louder than they are. Who wouldn’t, with titles such as Self-Portrait as a Gorgeous Tumor (2001)? She lacks the clumsy wit of a John Currin or the shriek of Lisa Yuskavage. Occasionally, her color grows pastel and high-pitched, as in Self-Portrait as a Wunderkabinet (2003) and Everything That Rises (2003), which ought to have been the title of a Mark Helprin short story. The details are rich, painted in the style, and echoes of the skill, of the Flemish masters. An early work, Self-Portrait as Gourmand (1994) is a Dutch or Flemish still life, complete with dark background and carefully rendered tablecloth, sedate and too imitative. With time she added other influences, especially the French and Spanish. (Does anyone try to come close to Fragonard these days?) Her settings appear to be old Europe, or their visions of an upper-class Eden. At any rate, these high-ceilinged rooms and verdant jungles do not say Brooklyn, where Heffernan lives. There is a touch of the Brothers Grimm in her woodlands, a lot of Vienna or Paris in her interiors.

For all this retrospection, there is nothing nostalgic or particularly contemporary in her visions. They present an imaginary time that is, to her, a surface to be worked or reworked. That is the postmodern element that saves her from imitation. Explicit contemporary references, such as including tiny portraits of George W. Bush and Condoleeza Rice in her painting Self-Portrait with Men in Hats (2007), fall flat. Bush has no connection with the dying Hapsburg regime in Spain; he would be nonplussed by Infantas. It’s a weak attempt at commentary. Her work is best when she takes center stage, cosplaying yet still herself. It’s an odd juxtaposition, akin to an actor who is never able to fully inhabit a role, but instead has characters written to fit a larger-than-life (and usually illusory) personality—an old-fashioned movie star or character actor. Yet Heffernan is, at best, life-sized, and remains slightly apart from the elaborate clothes and settings. Hence my use of the term cosplay. The term has an amateurishness that is unfair to Heffernan, and sounds over-critical, but I think no other term fits quite so well. A successful self-portrait is a sharing of the physical in a way usually limited to the psychological. In this way Heffernan’s self-portraits are not that at all. They are anomalous.

The millennium left its mark on Heffernan’s art. Through her career the trend has been toward more complex arrangements, compositions that build in careful proportions without giving in to grandiosity. The clarity of Flemish masters remains, but instead of a gentle calm, the tone is more ominous: echoes of Breugel and, increasingly, Bosch, have appeared. Millennium Burial Ground (2012) shares this dystopic, Brothers Grimm-like feeling. In the background, before a salmon-pink sky streaked with dark clouds, stands a tower, akin to Breugel’s Tower of Babel. In the foreground, a zigzagging fence hems in a crowd of wolves, alligators, and more. Heffernan herself is absent. Traffic signs of uncertain meaning stand along the fence. Wildness is contained, but the implication in the flimsy wooden fence rails is that it won’t stay contained for long. Whether the plenitude encompasses life or destruction there is always plenty. You can never grow bored in Julie Heffernan’s imaginary worlds, though the excess could overwhelm in lesser hands. Each of these worlds is presented as a portrait; addressed to the viewer, inviting the viewer to enter.

Pulling off the fantastic in art is a trick; Bosch and Dali did it without losing their place in art history, but so many others, even a William Blake, end up in a curatorial cul-de-sac. We place such a burden on representations of women in art, imbuing them with our dysfunction and our hopes, that it’s no wonder artists struggle sometimes. Heffernan’s women stand with one foot in the mysteries humanity has wrapped around women. Her "fantasias"—I offer that term in place of "self portrait"—offer neither the candy-coated babes of male fantasy nor the distorted images of fear. Instead they bring us through painting into a virtual world that is past and yet not past. We expect this from computer games and, at times, digital art. But sometimes we forget where it began, until Julie Heffernan reminds us.

- John Currin, Thanksgiving, 2003

- John Currin, The Bra Shop, 1997

- Will Cotton, Cotton Candy Katy, 2010

- Will Cotton, Ice Cream Dona II, 2011

- Julie Heffernan, Study for Self-Portrait as Flat World, 200

- Will Cotton, Landfill 2012

- Julie Heffernan, Millennium Burial Mound, 2012

- Julie Heffernan, Self-Portrait as a Great Heap, 2009

[1] Quoted in Baldwin Gallery brochure, 2008; ISBN 0-9671449-9-X