William J. Simmons: Tell me about your shows in Dallas and New York City. What direction is your new work taking?

David Salle: The show in Dallas brings together paintings from the last five years or so that, for the most part, are configured as vertical stacked diptychs: 2 panels conjoined along a horizontal spine; sometimes they become a horizon line. There are some other configurations—side-by-side diptychs, multi-panel extravaganzas, but that’s the dominant mode. Like a marine painting: sea below, sky above, although in this case the "sea" panel is a portrait of a woman, sometimes a full figure, sometimes a rather tight close up. And the "sky" panel is an image of a tangle of wire, an abstract image made more abstract by the under-painting, as well as finger-painting marks on top of the printed surface. Into these diptych formats, I’ve occasionally added hand thrown ceramic elements on the upper panel, which kind of mirror either the "subject"—the face in the portrait, or more often, the compositional energy in the painting.

The New York show will be of highly composed paintings—everything takes place all in one rectangle. They are collage-like in approach—disparate images organized into a dynamic pictorial space. Both groups of paintings, both shows, stay close to my original idea of simultaneity—the ability to hold two or more things in your head at the same time. Which I suppose is another way of saying I’m interested in making work that supports the idea of a prolonged viewing time.

David Salle Silver 10, 2015

pigment transfer on linen

84 x 60 inches

Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

WJS: Your treatise on "The Forever Now" at MoMA exploded onto the scene and has been considered among the best reviews of that divisive show. Why did you decide to write that piece, and to what end?

DS: Laura [Hoptman’s] show was obviously one that cried out for commentary. For one thing, it was the first such show at MoMA in over 30 years. For another, Laura clearly wanted to stir up a controversy about quality, so it would have been churlish to deny her. Apart from that, I wanted to show, with as much good will as I could muster, the range of achievement—as a general principle. That is to say, not to take everything at face value, but rather to try to look at what exactly had, or had not, been done.

WJS: In 1986, Lisa Phillips said of your work, "Salle has largely displaced the eroticism of his subject matter into the act of painting itself, demanding an erotics of art as a way of encountering the world." I’m interested in the erotics and this act of displacement Phillips describes. Do you see your work as engaging in this process, and what is the nature of this "erotics of art"?

DS: When asked what he thought about the so-called erotic element in my work, and the feminist critique of it at the time, Philip Johnson said that "…the slight tumescence you feel is part of looking." Which was a great thing to say, considering his age at the time; Philip was then well into his 80s. What Lisa said—something I had forgotten—does seem to capture the feeling I had about my work during those years, or one of the feelings anyway. It’s hard to say what was the exact nature of that "erotics"—but isn’t painting always involved with some act of displacement, one way or another?

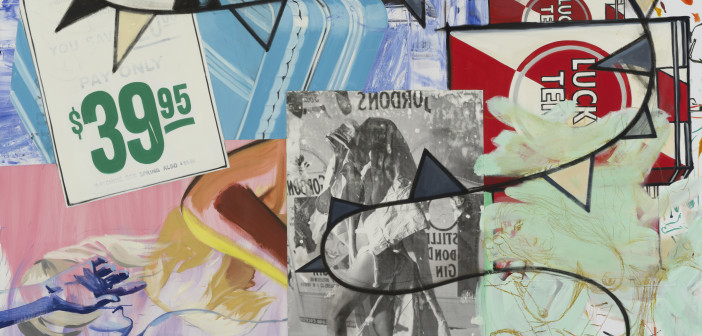

David Salle Carny Mind, 2015

oil, acrylic, silkscreen, charcoal, crayon

and archival digital print on linen

96 x 70 inches

Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

WJS: Could your work be seen as a queer or "queered" act, since it transfers issues of gender and sexuality into the medium itself, as Phillips describes? Charges of sexism have been levied against your work, but it seems that something more complex is happening—a process of enlivening the medium with gender play, a queer engagement with paint and photography.

DS: I love your idea—I don’t know if my work, or my idea about how my work operates, fits into queer theory exactly, but it is a kind of lovely metaphor. I think about something I call the "transformational grammar" of images and painting. How something is painted is part of the image; the image is arrived at by being painted, which might sound like a tautology, but is actually a very important idea. The HOW and the WHAT are inextricably intertwined—as well as with photography, as you suggest. I’m interested in the interchangeability and reciprocity of images and materials, how they can be made to trade places—hardly a new idea by the way—and how paint in one form, say a tight spiral of color, can emerge in an entirely different form: a cartoon duck, just to use one trivial example from an early painting of mine. This reciprocity is a deep part of painting, perhaps the deepest part, but it’s the real stuff of it. You see it in Matisse and Picasso of course—Matisse even more. As I recall, most of the Feminist objection to my work was about subject matter. I like to think that what I’m doing is very fluid, both imagistically and spatially, with subject and object not especially fixed, and giving a kind of wide berth to subjectivity. I’m attracted to the idea of one thing sort of turning into another—many artists have said some version of the same thing; I think it’s pretty basic to painting and to art generally. If these ideas resonate with queer theory, well, so much the better.

WJS: It’s no mistake, I think, that you bring up camp—traditionally an arena of queer expressivity—in your review of "The Forever Now". Isn’t abstraction always dealing with camp, as Amy Sillman argues in "Ab-Ex and Disco Balls"? Why was camp one of your criteria of evaluation in "Structure Rising"?

DS: I’m not sure I agree with you there—that abstraction is always dealing with camp, except perhaps in the broadest possible sense of one thing standing for another. Camp—something that encompasses parody, deliberate cliché, exaggeration, etc.—is now so widespread, so mainstream, that it’s hard to actually be camp anymore. Camp is the language of the insider, but it’s now shared by too many who are a little too anxious to show that they’re in on the joke. That’s not camp—it’s just over-population. True camp is generous in spirit—it’s about liking things; it’s not jaded. There might be a confusion between camp and kitsch. Damien [Hirst’s] shark for example is kitsch, not camp. Not all bad taste rises to the level of drag.

But as for painting—I just think it’s hard to make a good, convincing painting, of any type. And inevitably, it will in some way reflect the larger cultural sphere, so it should be no surprise that disco balls and ab-ex comingle.

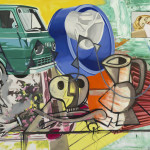

- David Salle Freak Flag, 2015 oil, acrylic, crayon, archival digital print and felt on linen 84 x 96 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Self-Expression, 2015 oil, acrylic, charcoal, archival digital print and pigment transfer on linen 102 x 78 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Home Guard, 2015 oil, acrylic, crayon, archival digital print and felt on linen 92 x 59 1/2 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Yellow Fellow, 2015 oil, acrylic, silkscreen, crayon and archival digital print on linen 78 x 108 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Silver 15, 2015 pigment transfer on linen 84 x 63 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Silver 14, 2014 pigment transfer on linen 96 x 53 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Silver 12, 2015 pigment transfer on linen 84 x 60 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle This is the Fun, 2014-2015 oil, acrylic and archival digital print on linen and canvas 70 x 96 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Faster Healing, 2014 oil, acrylic, crayon, archival digital print and pigment transfer on linen 77 x 96 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Silver 1, 2014 pigment transfer on linen 84 x 60 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

- David Salle Odes and Aires, 2014 oil, acrylic, crayon, charcoal and archival digital print on linen and canvas 61 x 84 inches Image courtesy Skarstedt, New York

David Salle: New Paintings is on view at Skarstedt Chelsea (550 West 21st Street NY) through June 27, featuring all new work from two recent series: the Late Product Paintings and the Silver Paintings.