By CHARLES GIULIANO

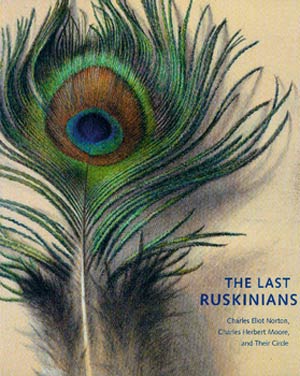

During a tour of the small but intense and insightful exhibition “The Last Ruskinians: Charles Eliot Norton, Charles Herbert Moore and Their Circle” the co-curator, Virginia Anderson, and I paused before the remarkably detailed, full scale study of a peacock feather by Moore. “We looked at it under a microscope and it was just amazing,” she said. “He created it using tiny brushes.” It evoked comparisons to a similar study of a feather by Moore’s mentor the great British art historian and watercolorist John Ruskin. She suggested that I borrow one of the magnifying glasses placed at the entrance of the exhibition for the convenience of visitors.

Over lunch at the Faculty Club I suggested to Theodore E. Stebbins. Jr., the curator of American Art for the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, that there were micro and macro approaches to the exhibition which he and Anderson had organized. That it entailed the most demanding observation of obsessive detail in the intimately scaled drawings and meticulously rendered watercolors and that on the macro level these works evoked larger analogies and questions about the very nature of the Fogg Art Museum and its legendary approach to connoisseurship and teaching through the study of objects. All of which was inspired by the writing and pedagogy of Ruskin. Both the works on view by Ruskin, the best drawn from some 70 examples in the collection, and images by artists he inspired, reflect his dictum of “Truth to nature” and the notion inscribed as a display text on the exhibition walls that “If you can draw one leaf you can draw the world.” There are several examples of carefully rendered leafs as well as sprigs of blossoming branches to illustrate his points. But Ruskin and his followers were also capable of grand vistas including his detailed study of a boulder surrounded by forest. There are a couple of landscape watercolors by J.M.W. Turner the British artist whom Ruskin endorsed as the then greatest living artist.

For Ruskin and his followers, several of whom were part of the founding art history faculty at Harvard including primarily Charles Eliot Norton, Charles Herbert Moore and those whom they trained, clearly God was in the details. There was also a direct line to Bernard Berenson and his influence on the aspirations and collections of Isabella Stewart Gardner. Stebbins offered that the Gardner is a “Purely Ruskinian institution” going on to describe a room dedicated to works by Denman Waldo Ross and others of the Fogg’s Rukinian circle as well as Joseph Lyndon Smith who trained at the Museum School. Bringing up Ross as a part of that tradition was particularly interesting as he was the mentor to the two young artists Jack Levine and Hyman Bloom who were brought to him as prodigies of Harold Zimmerman who discovered them in his art classes in the Jewish Settlement House in the old South End. The Fogg owns many of their early works which Ross donated to the collection. Hopefully one day they will be exhibited and published. Levine likes to tell friends that he was educated at Harvard but never earned a degree.

It was interesting to meet with Stebbins picking up a thread of dialogue that had been on hiatus since he resigned during the shakeup know as the “Friday Night Massacre” when Malcolm Rogers fired several curators at the Museum of Fine Arts. Initially, Stebbins planned to stay on as head of the new mega Department of the Americas but soon had a change of heart and decided to move on into what became, for a time, retirement. As a gentleman and scholar he declines to discuss any aspect of the MFA for publication. Clearly he has put that behind but it is fair to comment on a deep sense of disappointment over the circumstances of his departure. Retirement, however, did not sit well and he took the offer of former Harvard Art Museums director, James Cuno, to start a Department of American Art for the Fogg. He found himself in an empty office wondering just what to do next. Now he says there are not enough hours in the day to follow all of the projects. Eventually he was able to bring in Anderson who was one of his graduate students at Boston University where he very much enjoys teaching. Prior to graduate school Anderson was associated with Gallery Naga so its quite a transition from the world of contemporary art to the fine detail of the Fogg’s collection of Ruskinians.

“Right now I just have a corridor,” he said describing his turf at the Fogg. “But in the planned expansion that will grow to several galleries.” Even though the Fogg never had an American department or mandate still it has several thousand great works and continues to make important acquisitions. Some of these important works are scattered around the campus. I mentioned the Robert Feke portrait of the Isaac Royall Family which I know belong to the Law School. “Exactly” Stebbins responded. Significantly a number of works by Moore are described in the catalogue as “transferred from the fine arts department.” They were originally created under the tutelage of Ruskin and like his approach these studies and copies of art and architecture were intended as instructional materials in fine arts courses. So they were never intended to be viewed as they are seen here, as works of art. So this is an example of the kind of exhibition that results from the scholarly process of a curator working directly with the collection. Stebbins described a process of initially becoming curious about all of the Moore works and the 70 examples by Ruskin. The catalogue essays provide valuable insights and an overview of the early days of the Fogg and the meaning of that tradition.

Last year Stebbins organized a show of watercolors but opted against a publication because there was nothing new to say about well documented works by Sargent, Homer, Hopper and others. Even though such a book would have sold well. But he describes not being pressured to market exhibitions. On the other hand there was full and generous support to publish the current catalogue which does have new scholarly information. There is a different kind of mandate and pace to this kind of research exhibition and publication programming. He describes Harvard as a “Great place” for just those reasons as it is not a part of the show biz that prevails at too many major museums with their emphasis on the bottom line.

I brought up the issue of the 1985 exhibition by Linda S. Ferber and William H. Gerdts “The New Path: Ruskin and the American Pre Raphaelites.” Was there a need for another exhibition covering much the same material? Stebbins replied that the Fogg exhibition is significantly different as the Ruskinian style in art lingered on in Boston, because of the general support for the artists, like Moore teaching at Harvard, after the style was viewed as old fashioned in New York and replaced by the influence of the French Barbizon artists. Stebbins also discussed the importance of the fact that the Fogg group had great influence as directors, curators and trustees at the Museum of Fine Arts.

During a panel that Stebbins moderated at the annual meeting of the College Art Association in Boston, a couple of years ago, he presented a paper on forgeries and the role of connoisseurship in discovering and evaluating authenticity. During the period of questions and answers he did not really respond to my asking if he felt like a dinosaur in continuing to pursue connoisseurship where the shift in teaching and curating has dramatically turned to philosophy and theory.

Under congenial circumstances I got back to the topic and tried to pin him down. In light of the subject at hand and its deeps roots in the Fogg’s traditions I asked if indeed he might be the “Last Ruskinian?” There was a humorous response but also a touch of concern about the intent of the inquiry with its implied critique of theory driven approaches to art history. He offered some anecdotal remarks that indicated that he understood and appreciated the nature of the question. But he also firmly stated that he reads the work of these scholars and learns from them so he does not feel threatened by that approach. He expressed a very catholic willingness to use any source or technique that helps in the understanding and authentication or provenance of a work. He brought up the controversy of the Matter Pollocks which has been taken on by the Fogg’s conservation and research team. So far, there have been the approaches of the connoisseurship of the scholar Ellen Landau who declares them as genuine, fractal analysis which concludes that they are not authentic, and now the chemical analysis of materials by the Fogg’s researchers.

Were he in the position to make an acquisition such as the Matter Pollock works I asked just what would be his approach to rely on the eye or science? Basically Stebbins described the process in recent acquisitions of works that he and Anderson had decided for and against concluding that you have to be absolutely certain both in terms of authenticity and that the work is a significant addition to the collection.

Having read through the catalogue I suggested that with the change of a few names and circumstances the didactic loyalty to all of the eccentricities, strengths and weaknesses of Ruskin, who dominated the art thinking of his day, might also describe the influence and fanatical loyalty attached to the persona of Clement Greenberg. Aren’t the serio-comic highlights and pratfalls of the Ruskinians all too like those of the Greenbergians, some of whom, like Michael Freed and Kenworth Moffett, had close ties to the Ruskinian Fogg? The subtle Stebbins response was that from time to time there are “critics who think they have the answer to everything.” Much to his credit, while rooted in the objects themselves, Stebbins is open to all of the sources when trying to extract from the work its full measure of significance and meaning. This is precisely what makes him such a great curator and teacher. It is just what made me want to go back and take another long hard look at the exhibition.

Just what to think about these works and their obsessive, fussy details? There are certainly remarkable works such as Moore’s study of details of Lincoln Cathedral. One might appreciate the conservative appeal of works by William Henry “Bird’s Nest” Hunt. A wonderfully illustrative and decorative rendering of an old birch tree in a winter landscape by George Hawley Hallowell reminded me of Maxfield Parrish. I was surprised that I hit the mark when Anderson informed me that “They were cousins.” Who would not be rightly stunned by the details of Ancient Egyptian relief in a rendering of the temple of Philae by Henry Roderick Newman? It was nostalgic to see works by Joseph Lyndon Smith which I recalled from a horde in the basement storage of the Department of Egyptian Art at the MFA where I worked as an intern in the 1960s. I always admired the deadpan realism of those paintings.

But there was also the feeling that however remarkable the skill in rendering and attention to “Truth to Nature” that the Ruskinian manner was to its time as much of a Judas goat and dead end as the Color Field Paintings of the Greenbergians. It’s what happens when too much thinking and not enough spirit goes into art making. While it is admirable to possess a great eye and hand, as did Ruskin’s primary follower here, Moore, it is also a sad folly when the art lacks a greatness of humanism. Yes there is the admirable Ruskinian mantra of “Truth to Nature.” But there is also the Jackson Pollock response when Hans Hofmann suggested that he look more at nature. Pollock replied “I am nature.” Perhaps that’s the Truth that is lacking here.

- The catalogue for the Fogg Museum’s Ruskinian exhibition.

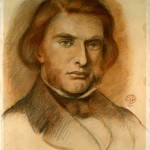

- A portrait of Ruskin by Dant Gabriel Rosetti (not in the exhibition).

- Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. curator of American Art for the Fogg Art Museum.

Fogg Art Museum and Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University

"The Last Ruskinians: Charles Eliot Norton, Charles Herbert Moore and Their Circle" is on view April 7 – July 8, 2007 at The Fogg.

Catalogue and Ruskin images courtesy of The Fogg.

Stebbins photo by the author.