While walking through the National Gallery some years ago from some distance across a large space I spotted an unfamiliar synthetic cubist painting from Picasso’s studio series. From afar there was something off about it that drew me forward for closer examination. Reading the wall label my suspicions were confirmed that there was something not right about the painting. It wasn’t by Picasso. Instead it was a painting by Arshile Gorky.

Of course, I thought. That makes sense. Having previously seen the Gorky retrospective at the Guggenheim I was familiar with the fact that during his juvenilia he had created series of works channeling artists from Gauguin and Cezanne through Picasso. These early studies commanded interest only as they were transitional to the breakthrough when Gorky, under the influence of the Surrealists in exile in New York during World War Two, the circle of Peggy Guggenheim, broke through and created the first truly original paintings of the New York School.

That these early “appropriations” (as the term is used today) were of interest only because they were transitions to the “original” works that, in hindsight, invested the studies with value as part of the oeuvre of a major artist of his generation.

Studying that work in the National Gallery made me rethink my paradigmatic assumptions about Picasso. A bit of neo-Platonism, as it were. In what way was the Gorky like a Picasso? And in what way not? Art historians love to engage in such exercises, like side-by-side comparisons of works from the same phase of analytical cubism by Picasso and Braque, or those nightmarish graduate level slide exams where we were required to identify cathedrals on the basis of being shown a dozen naves. Over coffee we compared notes and tricks for tell-tale details and clues. It wasn’t so much that we knew the naves as the particulars of slides in the collection.

I don’t know if they do that anymore in graduate school. It seems they read and talk about art more than actually look at things. For my generation, the ultimate test was to discover a forgery, and why it was forged. It was fascinating detective work. Shown two slides, side-by-side, of drawings by van Gogh, for example, we had to argue which was authentic and which was false. During a Rembrandt seminar I recall the class looking long and hard at “The Polish Rider” in the Frick. There was something terribly wrong about the horse, but, overall, a great picture. Today, it is not attributed to Rembrandt.

Why, however, do we think less of a great work when it gets declassified? Priceless masterpieces end up in basements, like the Minoan Snake Goddess in the Museum of Fine Arts which is now believed to be a modern forgery. In hindsight the tiny ivory and gold piece always seemed far too classical for its second millennium BC attribution. It is still on view perhaps because the curators just don’t have the heart to remove her.

The works on view in this exhibition at MIT, “Sturtevant: The Brutal Truth,” are all too readily familiar. It is filled with remakes of icons by Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Beuys, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Paul McCarthy and Frank Stella. Just the kind of eclectic selection one might encounter at MoMA. Of course there is nothing unique about artists recreating works by the masters. That has been a standard of the education of the academy for centuries. The notion is to walk in the shoes of a master before setting off to find your own stride.

The point here is that Sturtevant never took that next step. Never developed her own work. But has walked all her life in the shoes of others. But, I should be careful, because this is where it gets tricky and risky. You may reveal yourself to be a dunce. I am recalling the sly smile last night across the dinner table after the vernissage. Looking for some help with this writing task I tried to elicit some insights from John L. Moore, the artist husband of List director, Jane Farver, as well as other guests, critic, Anne Wilson Lloyd, her husband, and a young gallerist from New York, Amy Davila of Perry Rubenstein Gallery. They weren’t being very helpful. But the banter was fabulous. I suggested to John that there might be three possible approaches to writing about Sturtevant. Plan A would entail heavy duty theory. Not my strong suit. Plan B would be more journalistic just reporting on stuff and getting the flow of the jive. Plan C would be just a blowoff. To appeal to the nay-sayers and Republican vulgarians who lurk and multiply like rabbits in the heartland. To give comfort to those who see contemporary art as some kind of liberal conspiracy. The Bushies.

With a wonderful flourish Moore suggested that I combine all three approaches. “There you have it,” he said provocatively. “With equal weight, at least 900 words to each segment.” Later when the artist, Farver, and Mario Kramer, the director of the Frankfurt based museum which organized the show rose to speak, Moore looked at me with that “watch it Charles look.” Pay attention before you make a fool of yourself. Kramer talked about emptying the museum of its permanent collection and installing Sturtevant, more than a hundred pieces, in the entire space. He referenced that trauma with some humor and the comment that it may take several years to recover from the experience. But all in the service of one of the most original and provocative artists of her generation. That snapped my head back.

The evening had started with misgivings. This was an exhibition I was not anxious to attend. Over the years I had seen the work on a number of occasions going back to a show at Stux Gallery during the last millennium. It was difficult work that went along with the artist’s crusty social manner. I was on hand during last minute preparations prior to the opening. Now in her 70s, she seemed little changed. When I approached her it was like embracing a cactus. She is a tough looking woman with a weathered face, slim body, and a shock of punk cut, gray hair. Her eye contact is fierce and devouring. She is a true warrior woman of the avant-garde, for that, god bless and keep her.

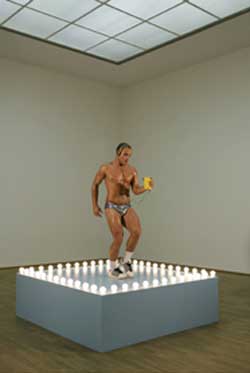

There was a lot of snickering as I huddled with various artist and critic friends. Each trying to pry out of the other some thread of meaning about the challenging work that is both obvious and oblique. Yin and Yang. At one point, Sturtevant, who had arrived at the height of the opening to a great round of applause, approached the slim, young, boy toy, go go dancer in silver briefs who was a living element of “Gonzales-Torres Untitled (America),” 2004. He was rather oblivious to what was going on around him and tuned into a Walkman headest. She screamed to get his attention and demanded he take off the earphones and listen to her instructions. The boy looked freaked. Nodded and changed his dance style. As she swept by we asked what she had said to him. “More disco,” she replied, “He is supposed to be a disco dancer.” Looking back he was now appropriating John Travolta’s moves from “Saturday Night Fever.” My heart went out to the sad young narcissist. What a way to make a living.

The issue is when is a Warhol not a Warhol but instead a Sturtevant? And how is a Sturtevant of a Warhol not a Warhol but a Sturtevant? Truth is that even “original” Warhols aren’t Warhols. Like the series of “Flowers” by Sturtevant on view here. For openers, Andy boosted the image from a Kodak ad. Later got sued and settled. Of course, while he did not initiate the image, there is an obvious difference in scale, color, and context between a small ad in a magazine and epic scaled canvases such as the remakes in this exhibition. You wonder how Andy felt about having his work recreated by Sturtevant? It is staggering to learn that he actually loaned Sturtevant the original silk screens in order for her to make these pieces. So they are precisely like “original” Warhol pieces. Which were mostly not actually executed by Warhol but by the ongoing series of assistants in his factory. The authenticity of the work exists only in the concept of the artist. It is ultimately reproducible particularly if the artist consents to loan the templates. When, during an interview, Warhol was asked how he made the work he answered, “I don’t know, ask Elaine.” It is interesting to note that some of the funding of the exhibition was provided by the Warhol Foundation. So Andy continues to support the work.

What gives her work credibility is that it started in 1964 and, initially, almost entirely involved artists who showed with Leo Castelli. He understood and appreciated her concepts. Which is not really true of the art world in general. The catalogue essays note that almost all of her work resides in European collections. That no major museums own pieces. That the art world has dismissed her as too cold and conceptual. She does not regularly get included in surveys of either pop or conceptual art. For a decade she stopped working out of despair. So there has been a lot of adversity and mistreatment. Why add to that here? But there is also a difficult learning curve. How to overcome a natural inclination to apathy and ridicule. It was excruciating, for instance, to sit through her Beuys video. The production values were at least as horrendous as that landmark Willoughby Sharp home movie of Beuys lecturing. Only the strong survive such an experience. I clocked in at about 20 minutes of the 30 minute video. Which is a lot. More than that would test my sanity.

While the Warhol/ Sturtevant’s and the Stella/Sturtevant’s are disarmingly successful simulacra, the Johns/ Sturtevant’s are not. This is the underbelly and flaw of her approach. While Warhol and Stella were all about concept, the essence of Johns is touch. The small “Johns Flag Above White Ground” is a disaster. What a mess. Wrong, wrong, wrong. Let me say that again, Wrong. The richness of a Johns surface is here just a glump of wax over newspaper. Also, the series of “Johns Light Bulb” was similarly jolting. Johns is the greatest painter of his generation and Sturtevant would have been best advised to avoid such wretched comparisons.

One interesting aspect of this show is that Sturtevant, very early on, picked the winners. She has a great sense for the icons. They were all by living artists and peers. It was that keen eye that gives this body of work such value today. She backed the right horses. Although Stella has slacked off. Interestingly, she remade the early stripe pieces which are his most durable works.

Pausing for a moment, I wonder if I have added to or detracted from the critical dialogue. The catalogue essay states that, “From the beginning, Sturtevant’s approach was considered so provocative and subversive, so difficult to pin down that most art critics and museum curators kept their distance. After all in each respective aesthetic discourse her work lays claim to validity in a manner which art ideologists find uncomfortably difficult- if not impossible- to objectify.”

Sorry John, I am not sticking to the game plan we discussed. Don’t quite know if I followed the A,B,C approach. And certainly not 900 words for each. And I may have fallen into the ditch of revealing more about my critical limitations than offering insights about the work. But, hey, I gave it a shot.

Before we get out of here there is that issue of why this work is not appropriation as we understand the term. On that I will allow the artist the last words, “I am not an Appropriationist by token of intention and meaning. The work cannot be located in the discourse of copies, paying homage, saying anyone can do it, and definitely don’t think everyone should have to understand art. I’m talking about the power and autonomy of originality, and the force and pervasiveness of art.” Power to the people.

- Arshile Gorky, Composition with Head, oil on canvas, 1936-7.

- Sturtevant at MIT.

- Sturtevant at MIT.

Links:

MIT List Visual Arts Center

Perry Rubenstein Gallery

"Sturtevant: The Brutal Truth" is on view May 11 - July 10, 2005 at The MIT List Visual Arts Center.

A concurrent exhibition of Duchamp images on view at:

Perry Rubenstein Gallery

527 West 23rd St.

NY, NY 10011

Sturtevant images are courtesy of the artist and The List.

Gorky image found using Google.