Michael Bühler-Rose lives and works in New York. He received a Fulbright Fellowship to India, received his BFA (2005) from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and MFA (2008) from University of Florida. His work is currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston as part of the current the SMFA Traveling Scholars exhibition. Currently, he is a Visiting Assistant Professor at the Rhode Island School of Design. He spoke with Matthew Gamber this April on his most recent show at Carroll and Sons in Boston.

Matthew Gamber: Can your describe the source of the objects you've used for your series Little Indian Still-Lifes and what significance they have?

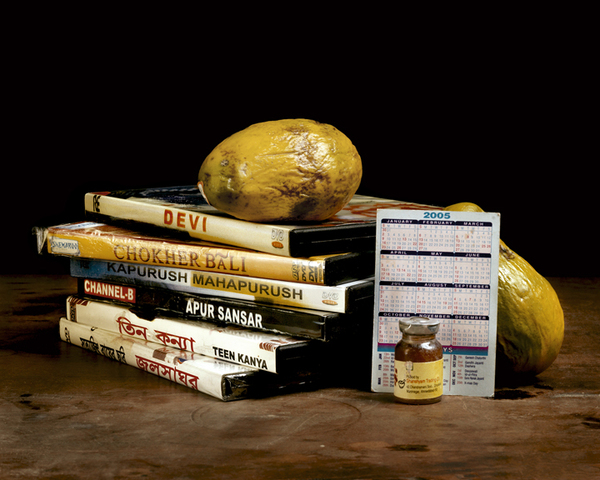

Michael Bühler-Rose: All of the items are purchased from the "Little India" sections of New Jersey, like Oak Tree Road in Iselin and Jackson Heights in Queens, NY. How the objects have ended up in these areas is through a mixture of imports directly from India, as well as items that are traditionally made in India but now have been “outsourced” to the USA. There is also seasonal Indian produce like mangoes, but are actually imported from South America, so they are not quite "genuine" Indian mangoes, but are close enough for use within the community.

MG: Still-life has been progressively marginalized into an academic exercise–for example, painting fruit bowl as a lesson in rendering surface with paint. Do you see the photos as a tribute to the genre, or an re-examination of what a still life entails?

MBR: My interest in the still-life is definitely not in its traditional pedagogical approach, but rather to look at a more specific still-life tradition, the Dutch still-life. My particular attraction is the political history of the Dutch Still-life: how it functions as a symbol of Dutch nationalism as evidenced by the results of Colonial power, via the Dutch East India companies "exotic" imports and a marriage of local Dutch products.

MG: That opens up an entire backstory, and instead of questioning what objects are in a still-life, but why a still-life exists as a subject at all, and how what function they serve in their intended audience.

MBR: What is curious to me is how a seemingly banal image of a pile of pepper has a highly complicated history. This was apparent at the time, although I think now pepper is not considered particularly exotic or hard to come by. But items like this symbolized not just lavish dining, but the ability to lavishly dine, through global power. This re-examination looks at the shift of imports from the east to the west and recognizes a very different dynamic.

The items in these Little Indian Still-lifes have a slightly more complicated history, not the tradition of absolute Western Colonialism, but rather of a sort of reverse colonialism or rather a setting up of a "Little India" complete with items easily available in any shop in Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, or Delhi, whether it is a Bengali film, a mango, or an item needed for a Hindu ritual.

MG: For these communities, having familiar things is now based on market willing to import exotic objects. How do you think that changes one perception of their own culture, based on the need finding suppliers based who is willing to import what used to be common household goods?

MBR: In regards to your question, I don't think an outside market affects these communities, since the shop owners are often importing items themselves, as well as selling within the community. I think there may be outside people coming to buy some things here or there, but it is definitely focused on the needs of the Indian community, which is enormous. For example, Edison, New Jersey has one of the most concentrated Indian populations outside of India.

Certain items like DVDs are obvious bootlegs (some even include advertisements as to the location of the shop to get more of these copies) making it much easier to import a whole store full of DVDs and VCDs by fitting a few originals in a backpack.

Other items like a large grinding stone common in most households in India, especially West Bengal, are almost impossible to come by, which I assume is because it is a huge stone which usually only costs a few dollars in India would have to be marked up substantially to make any profit because of its size and weight, it has also probably been replaced with electric spice grinders, even though it creates a very different result, spice paste as opposed to a spice powder.

MG: In many traditional still-life paintings, there are clues to moral reminders, even to the point of reminding one of their own mortality, with inclusions of various momento mori. Do your photographs have a comparable function?

MBR: At the time of these types of paintings, any religious/spiritual sentiment was restricted to more subtle and general spiritual themes. Although my initial attraction to the tradition was definitely a concern for its inherent politics, I am very interested in this cloaked spiritualism. In my pieces there are still the rotting fruits, flickering candles, clocks, calendars present all representing the passage of time, mortality, etc. which are all present in Hindu thought.

This approach has led me to think more about how to connect my own internal spiritual life to my art practice in a more complex way than the Dutch still-life tradition allows. I find a certain amount of kinship with those Dutch painters as it is a complicated position to make work that satisfies an inner spiritual craving yet not falling into the binary of either too new age-y or overly didactic but rather a wholly spiritual aesthetic experience. I don’t think my particular still-lifes are invested in creating that type of experience, but some of my newer projects look towards that goal slightly more directly.

MG: In still-life objects is merely residue, or a placeholder–a symbol for another idea. As the genre progressed throughout the development of mercantilism, what began as religious symbols were later transformed into symbols of skill and wealth. Do your images symbolize a hybrid of this change?

MBR: In some newer projects, I more directly confront the links between spirituality and religious function in art, not just where it is historically obvious (like updates on Dutch Still-lifes), but where it is replacing and/or even antagonistic to a religious ideal, but still overtly very religious in terms of rituals and hierarchy–an artist as priest, museum as temple, the art object as deity and the installation of it as the consecration of the deity. The relationship between viewer and image has been wrought over for thousands of years in India resulting in quite complex visual theory.

The symbols of a lavish lifestyle and the symbols of a temporary existence are the same, it is just that the former has not had enough time applied to it, allowing the fruit to rot, the fish to decay, etc. This resulting tension could either lead one to think, “You only live once, so lets just go for it” or slightly more thoughtful, “if I am going to die, what is the point of it all, and what is next?”

- Michael Bühler-Rose, Mangoes, DVDs, Calendar & Honey, 2009

- Michael Bühler-Rose, Maps, 2008

- Michael Bühler-Rose, Radha-Damodara, 2009

Michael Bühler-Rose

Carroll and Sons Art Gallery

"Little Indian Still-lifes" is on view through May 7th at Carroll & Sons, located at 450 Harrison Ave., Boston, MA.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Carroll and Sons.