Most of Vermeer’s canvases are of a similar type – quiet, low-key in color, and asymmetrical but strongly geometric in organization. Often times we see women in interiors, alone or with a servant, engaged in some activity, such as writing, reading letters, or playing a musical instrument. In this painting we see a virtuous woman pausing to gaze through the window as light bathes her during her “morning toilette.”

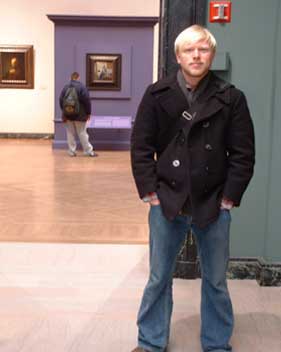

In contrast to the quiet scenes in Vermeer’s paintings, the scene the museum has created for this Vermeer is all but quiet. The large purple wall with crown molding epitomizes this thought, as it sits in the back center of the gallery and majestically displays what is being referred to as simply the “rare Vermeer.” The astute viewer can even get a glimpse of the framed painting and its backdrop of purple from other points in the museum. From the Impressionist gallery on the west side of the museum, the bright purple and the showcased painting draw intrigued viewers into its presence. This not only gives the painting pronounced visibility but also positions the painting in an “ennobled” manner.

Why is this Vermeer in a position of superiority and privilege? With endless sales in posters, postcards and a best selling novel creating some mystique, Vermeer is without a doubt an artist of widespread fame and marketability. The question for the museum is then simply, how to compete with that kind of publicity.

While marketing companies and kitsch frame shops create a surplus market from Vermeer’s paintings, the one area they cannot compete with is the authenticity the original that gives reason for the reproductions. In this case, the more Vermeer gets exchanged in frame shops and in art history books, the more this "aura" is peeled from its shell, making the original more malleable and divorced from its particular position in time and space (1). In this sense the rationale for the purple wall is perhaps to distinguish, to connote royalty to the Vermeer painting, to give it an “aura” that no reproduction can offer. This is what the museum wants and needs to compete in the Vermeer market.

Walter Benjamin's seminal essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” describes the affect mechanical reproduction has on works of art. For Benjamin, the more a work of art is reproduced, the more the “aura” of the “original” is lost. In this case, the more Vermeer gets exchanged in frame shops and in art history books, the more this “aura” is peeled from its shell, degrading the original. This aura and originality is important for the museum to preserve because it gives viewers a reason to frequent the museum, each time contributing their money.

The preservation of Vermeer’s status as one of the greatest Dutch painters of 17th century must The preservation of Vermeer's status as one of the greatest Dutch painters of [17]th century must also be redeemed to rationalize such extravagant treatment. This is done with a key text on the opposite side of the purple wall describing the working conditions of the other Dutch artists of the period as “The Age of Vermeer.” Operating as a framing device, like the wall in relation to the doorway, this text positions Vermeer as king, insinuating that the other Dutch painters of this period are merely courtly sidekicks. Whether they painted before or after Vermeer or whether if they even knew him or not, they are relegated only to support the sovereignty of Vermeer.

The museum’s installation and promotion of the painting is perhaps a necessity. With the small scale of the Vermeer, it certainly could have disappeared in the expansive gallery without some differentiation. With such an important loan in town the museum had to impress upon the city the Vermeer’s importance and its need to be “seen.” The only way for the museum to do that is too sell the aura of the original, the small portion of the aura that hasn’t been withered away by mechanical reproduction. In this sense, it becomes impossible to "see" the Vermeer, only its framing devices that make its ennobled position active; the true focal point of the exhibition.

----

1 For Benjamin, this was by no means something to be lamented; who felt the mechanical reproduction of artworks opened up new political possibilities for works of art, specifically in film.

The “Rare Vermeer” is on display in the Brown Gallery on the second floor of the Evans Wing of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston until February 22, 2004.

All images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York.