Christopher Lamberg-Karlovsky lives and works just outside of Boston proper. He received an MFA from Boston University in 1992, and an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1999. His work was recently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston as part of the SMFA Traveling Scholars exhibition. He spoke with Chris Volpe this May.

Chris Volpe: You were present, seated nearby your installation at the MFA, since it opened. Can you describe the typical reaction to your installation pieces and relate that to how you hope they will be received and understood?

Christopher Lamberg-Karlovsky: About thirty percent of the viewers took one look at the cases hanging on the walls and they immediately decided that they weren't interested; they'd seen enough disorienting objects on enough contemporary art walls, and they finished looking before they even noticed the paintings. I heard some hilariously cutting remarks. And then there were the folks who walked in and locked on. They entered the room, looked puzzled or pleased for a moment, and then began walking slowly from piece to piece. I had to apologize constantly for motion detector alarms sounding off because folks inevitably craned in for a close look.

CV: Is your interaction with the suitcases and with the viewers an intrinsic part of the installation then?

CLK: There's definitely a performative aspect to what I'm up to. In a sense, my work hybridizes painting, sculpture, installation and performance. I think the totality constitutes the true body, and that includes the traveling, the personal interactions and the overall effort to engage and to expand the format of my art. I want to be as generous as possible with the sum of my diligence. It's a new way for me. I've always been a studio monk, an anti-networker if ever there was one. At this point though, I guess I'm carrying on a centuries old tradition of standing by my work, literally. After years of being extremely reticent to take my art out into the greater artworld, I've decided to do so as transparently as possible. I want my wares to embody as many of my motivations as possible, including my willingness to commodify my production. The suitcases give me the opportunity to take ownership of every aspect of being an artist. I must admit though, I'm still not convinced that selling this particular work is a good idea. My ultimate goal is to keep these pieces together. I've actually begun to view them as one piece.

CV: Landscape has been marginalized as a popular form of quasi-Impressionistic plein-air painting on one hand and on the other as a passé, naïvely nostalgic form of fantasy or propaganda, or both, depending on to whom you talk. Is your work a tribute to the genre, or a re-examination of what a landscape is, isn't, can, can't, or should be, in the 21st century?

CLK: I guess I'm shooting for all of those possibilities to some degree. I never thought of my work as a tribute per se, but I guess it's an appropriate term for part of what I do. I'm definitely a hero worshipper. I have my landscape-painter heroes, and I want my work to speak towards a certain reverence I have for their work and their painterly accomplishments, regardless of how deeply flawed the philosophical underpinnings of their work are.

At the same time, I'm cognizant of how our ideas of what constitutes a "landscape" are constantly shifting. After all, it's long been argued that landscapes themselves are cultural constructs. Currently, the way we manage land is one of the most important issues on the global table. Scientists, conservationists, city planners, architects, engineers and artists are all grappling with issues of sustainability and responsibility, all the while dealing with a degree of aestheticization that can't be avoided. I'd like to think that I'm one of a pretty large number of artists who, as Denise Markonish said in her essay for Badlands, "...are interested in linking history and the present by presenting an ecologically aware art that verges on the pre-apocalyptic but one that also holds on to the sublime beauty of the past, to preserve a history while pushing it forward into new terrain."

CV: Speaking of history, the conventions of the nineteenth-century Hudson River School play somewhat into your work, don’t they? Can you talk about how?

CLK: Some of the Hudson River Schoolers were, amongst other things, painting God's gift to Americans. The idea of Manifest Destiny was at play in the minds of several of those amazing painters. That problematic idea has not-so-indirectly led to the state of stormy affairs we're faced with today.

CV: So is your work a kind of reverse-image mirror of that historical American practice? Do the diminished size and confinement function as a foil to the appropriative nature of those “grand” canvases, which by their expansive physical size seemed to want to “contain multitudes,” in Whitman’s phrase?

CLK: The idea that the land somehow belongs to us has been so deeply ingrained in our psyches that even the protest songs of the sixties reflected a sense of ownership -- "This land is your land, this land is my land...this land was made for you and me." So yes, I think the somewhat foreboding nature of my work could be interpreted as a commentary on from whence the American landscape tradition has come. The cases are lined with black velvet; I prefer to see that choice as an ironic nod to the grandiose unveilings, from behind huge black velvet curtains, of some of the Hudson River School masterpieces. And then of course I do often quote their amped-up palette and their use of atmospheric perspective. I like the idea of condensing all that space and air that they captured in their paintings into a tiny format. I hope it reinforces the notion that those beautiful places are under serious pressure.

CV: You've also said that this series began as a kind of protest against the use of digital imaging instead of photographic slides to present paintings for museum or gallery review. What are some of the failings of jpeg images and how does your work circumvent "jpeg protocol?"

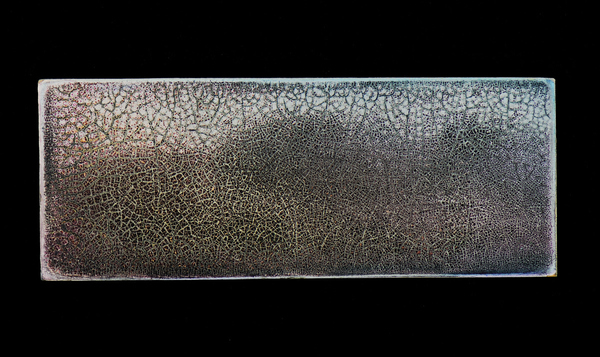

CLK: It's not so much slides vs. jpegs as it is original art vs. reproductions. I understand that curators, gallery directors and jurors are busy people who couldn't possibly do business without viewing reproductions. But I think for some art, the jpeg process is a nonstarter, the same way that slides were. For these pieces I spent a few years developing an extremely delicate technique usingBrownian motion and dehydration that is virtually undetectable on a monitor. Scale and visual subtlety are at the heart of the work, so the thought of using a jpeg to deliver a first impression was terribly upsetting. A great teacher of mine at the museum school used to say he wondered what Agnes Martin would've done had she been forced to make her way into the artworld using transparencies. I actually don't know how she did it, but I got the point.

My suitcase idea came about as a way to take my work to see people who'd be willing to look. I knew I had something that needed the experience of the physical engagement (as in, allowing the eyes and mind to do what they do upon approach), so I decided that it was time to take it to the streets. Also, I'd like to think that my paintings celebrate seeing to some degree. There's a real pay-off when you step in and step out; they shimmer and sparkle and appear backlit. A computer monitor delivers backlitness, but the dance of light is long gone.

CV: Where do you get the boxes? And are the paintings permanently affixed to them or are they really just stored in them?"

CLK: A company called Pelican makes the boxes. I get them mostly online. It's been suggested that I ask them to sponsor me. I'm pretty naive about that sort of stuff. As soon as someone suggested that I ask them for sponsorship, I immediately thought, "Oh no, I'm gonna get sued."

The paintings can be removed, but I hope they won't be. I like the idea that the cases are permanent safe harbor for their "nomadic" inhabitants. I should mention that it's not lost on me that those cases won't degrade for a painfully long time, or that they're used by the military who tear up the planet like nobody's business. I like pointing a finger at myself throughout my process. I use Purple Heart wood. It's harvested on the "edge" of rainforests in Central and South America. Two of the twenty-three species have become endangered from over-harvesting. We live in an age when, "...if the thunder don't get ya, then the lightning will." Regardless of our intentions, pretty much no matter what we do, we're doing damage.

CV: I wonder if we can relate those thoughts with recent attempts to link the work of abstract expressionists like Pollock or Rothko to the tradition of outsize American landscape painting by painters like Bierstadt and Church and various other movements in recent history to engage representational landscape again in a "serious" (as in "high art" vs. "fine art") fashion. Are the forms of this "tradition" still relevant?

CLK: Very much so. Idealization comes quite naturally to most of us. We all romanticize. If we didn't, we'd all be terribly depressed for good reason. The traditions of romance and idealization will keep running through everything that we do. Hopefully though, they will be infused with a consciousness and an awareness of the potential pitfalls of those perspectives. Even artists who've attempted to take the most deadpan critical look at the land, like the hugely influential photographers who contributed to the New Topographicsexhibition of the 1970s, were unwittingly embracing an idealistic notion that things could be better -- that they should be better. Their dismissal of a discernable style was a style unto itself, and it reflected their desires. To embrace the notion that humans are wasteful and destructive might just be the most romantic notion of all. It reveals our sense of hope. Maybe we are what we are; maybe destruction and waste is life. I hope I'm not sounding cynical here. I'm really not pessimistic. I think we're on the verge of doing some serious global healing. It can happen. It will happen.

CV: So, assuming there’s a future for the planet, is there a future for landscape?

CLK: There absolutely is. We live in an amazingly fascinating time. I think at every point throughout history there have been those who'd have you believe that their times were the worst of times. The sky has always been falling. These days are no different, except that now we've got a whole lot of hardcore evidence that just may indicate that we're right. Landscape artists these days are taking historical perspectives, activist and pragmatic perspectives, exploratory perspectives, aesthetic perspectives. They're taking it all on and their work is on the cutting edge of an incredibly important bunch of issues. And it's taking all sorts of forms, more than I can begin to list.

Clearly it's extremely important that we take a very hard look at our relationship to our environment and reckon with our position within and without it. Right now, the Kepler telescope is searching for earthlike planets out there. We have begun spending huge money searching for truly new landscapes that we can...use. I think landscape is actually where it's at. The marginalization is over. Landscape is Nature, and Nature, regardless of how it's represented and who's doing the representing, is a vacuum working as hard as it possibly can to bring everything to its still point as quickly as possible. We want to marginalize art that attempts to discuss that? Good luck to us!

- Christopher Lamberg-Karlovsky, detail and installation shots of Traveling Suite, mixed media, 2008.

SMFA Traveling Scholars Exhibition

"SMFA Traveling Scholars" was on view through March 3rd at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston - located at 465 Huntington Ave., Boston, MA.

All images are courtesy of the artist.