By MICAH J. MALONE

Camouflage is a modest exhibition dealing with artist’s use of pattern to construct paintings. The title of the exhibitions takes its name from Andy Warhol’s giant 37-foot canvas. While pattern has certainly been a major theme among post-war painters, the use of pattern obviously dates much further back. Aristotle first coined the term “horror vacui”, or the fear of empty space, and Islamic artists, the Victorian Decorative arts movement and many “outsider” artists later developed the concept as a stylistic approach to making very intricate patterns with symbols, words, pictures, or anything else. However, while the fear of empty space seemingly drives any pattern and its need to complete space, most of the artists in this exhibition seem intent to distinguish their approach to pattern, rather than distinguish a particular type of pattern.

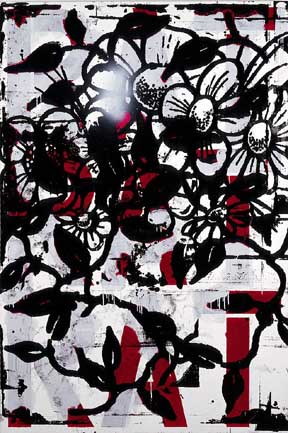

Pattern takes care of your composition. Once a design is developed, there is seemingly limited intervention in the overall look of the picture. One intervention might be Christopher Wool’s use of templates and a wet background to make inconsistencies throughout the painting: smears, runs and drips all break up the composition and insert the hand of Wool. His simple black on white floral motif is eerily transcended with breaks in the creation of the painting. His technique begins to define the picture as a “Christopher Wool” as opposed to simple pattern. For decades, Agnes Martin similarly exploited the inconsistencies of a given motif. Her washes and ruler lines have always ebbed and flowed with the movement of her own body, which breathes, shakes and meditates as she works. It is these types of interventions, or jolts in picture making that make Martin and Wool distinct. Ironically, through very familiar and simple patterns they have each carved a space where their particular pictures stand out. Virtually any art connoisseur can immediately spot a Wool or a Martin and it is the distinct “upsets” in their pictures that do it.

Both Wool’s and Martin’s pictures become distinct by way of how they are painted, as opposed to what is painted. Andy Warhol first became famous for a similar use of “upsets” in his pictures. His early series of car crashes, Marilyn Monroe and electric chairs are all distinct by way of his “indifferent” approach to proper silk-screening techniques and his embrace of off-register color. However, his monumental “Camouflage” is distinct for Warhol, in that it shows none of his trademark character. “Camouflage” is well crafted, clean, and the design of the government and void of any of the artist’s hand. This aspect makes it very different from the Martin and Wool pictures, in that the concept of camouflage itself is utilized. Camouflage might represent the artist himself and his well-known ability to disguise his intentions, motives and humanity.

Damien Hirst is represented by a new piece “The Kingdom of the Father.” The monumental butterfly painting (making its public debut here) is constructed in such a way to resemble stained glass windows found in old churches. Hirst is perhaps the only artist in the exhibition that seems intent to dazzle with his choice of pattern. Indeed, the amount of butterflies and the intricate filling of space best represents the origins of “horror vacui.” Perhaps his fear of empty space stems from a fear of not satisfying the public. Hirst is often noted as much for his theatricality and public relations as he is for anything else. His work (and presumably Hirst himself) truly needs the public. So much so, that pattern might be a natural way for Hirst to make sure everyone knows he’s giving his best, filling every bit of space for the greatest affect possible. Perhaps it isn’t a fear of empty space, but of an empty room.

- Christopher Wool, I Smell a Rat, enamel and alkyd on aluminum, 1989-94.

- Damien Hirst, Kingdom of the Father, butterflies and enamel on panel, 2007.

"Camouflage" is on view from August 4th, 2007 - November 4th, 2007 at the Portland Art Musuem.

All images are courtesy of the artists and Portland Art Museum.