By VICTORIA Z. ALEXANDER

Only painting which itself succeeds in beings a monstrous act succeeds in resolving and in reabsorbing the monstrosity of our lives, only painting that succeeds in becoming a mythic operator also succeeds in resolving the monstrosity of the social and of the social order… (Baudrillard in Genosko, 2001:42).I paint for eternity… I never use the word ‘art’… Art today has no meaning. It provides a service like an electrician does, or a baker. Since there are no rules in art, I am not an artist. So I say my work is anti-art… (Odd Nerdrum in Alan Jolis, 1999:118-120).

I. Beyond Art and Culture

The word “art” has become a troubling one in recent years. It is made all the more problematic by those in the “art world” who are part of the culture of endorsement. Curators like other promoters of our culture work, often despite their better intentions, to protect privileged westerners from seeing a world of violence and looking head on at the catastrophe in slow motion that is our Western culture. The painting of Odd Nerdrum includes some of the most striking representations of the inhuman produced in the past thirty years. A self-styled old master with something of the shaman about him (he studied under Joseph Beuys for a time in the 1960’s), Nerdrum paints unsettling scenes. These paintings are too radical to be considered as art by many in the contemporary art world and his work presents a deep challenge to that world and its defenders. Justin Spring, writing for Art Forum sounded a skeptical tone: “Though strong and technically accomplished Odd Nerdrum’s recent paintings seem at first like so much virtuosic pastiche”. Spring goes on to compare viewing Nerdrum’s work with the experience of seeing numerous works from the Metropolitan “coalesce into one work of nightmarish intensity” (Spring, 1993). Another New York based critic deepened the effort to protect us from Nerdrum’s work in a review of his show at the Forum Gallery:

His repertory of New Old Master showmanship camps in full feather past the footlights. Nothing here supports its own publicity as a Rembrandtian critic of modernity. Mr. Nerdrum is a parodist. That his parodies are mistaken for prophecies is a testament to P. T. Barnum’s grasp of public credulity and appetite for spectacle. In the end, failed prophecy is a form of nostalgia. It is dispiriting to see technique lavished on an art running on empty (Mullarky 2004).

Mullarky deeply underestimates Nerdrum’s “Rembrandtian” contempt for ingratiation.

Nerdrum has been received largely as an outcast in the official art world because his painting poses such a threat to it by evoking ideas that do not promote our culture or what the majority in the art world consider to be art. Nerdrum’s works do not possess a faith in humanism or ideologies of progress. This is not the art of enlightenment – it is an art of the inhuman – and the inhuman is something that occupies a far greater period of time in human history than does the human. Late modernity (the past half century) has been (in the West) merely a respite from the greater part of human history – a history of war and other inhuman activities. It has been a fertile time for humanism and Enlightenment thinking despite the presence of contemporary evacuations of the meaning of these concepts. Like Nerdrum’s art, these meanings are often ignored in the official circles of promotional globalization. Nerdrum’s art plays a vital role in the contemporary effort to open a breach where we may begin to consider the inhuman aspects of humanity (see also Baudrillard, 1998:97)

Nerdrum’s paintings are marvels – the kind of phenomenon that is so astonishing it can force us outside of our routinized cultural slumber. Nerdum’s art does this by being more “real” than our everyday perceptions of reality. Nerdum’s painting is neither a critique of violence nor is it art (in the terms of the art world in which he matured). Nerdrum’s painting then is a double challenge: a challenge to art’s inclusion in the culture of promotion and a challenge to contemporary notions that the inhuman has been tamed or surpassed by humanism. This is precisely where Nerdrum’s painting avoids so much of the banality and emptiness of contemporary art. What comes after art? Many things and among them is the painting of Odd Nerdrum.

II. Painting as a Monstrous Act

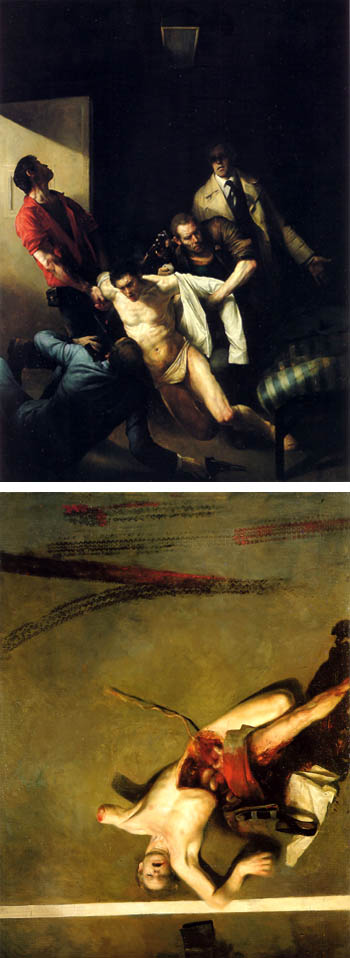

In the 1970’s some of Nerdum’s art was more concerned with the social. His The Murder of Andreas Baader is among the most overtly political paintings of the twentieth century. In this painting we see Nerdrum has already developed his command of “old master” style (following Rembrandt and Caravaggio in particular) for representing the contemporary.

At the same time Nerdrum was making paintings that eventually took him beyond the social such as Amputation. This painting may be also seen as a nod to Andy Warhol’s “accident” silk screens of the 1960’s and as a metaphor for Nerdrum’s treatment by the contemporary art world (and that of the Old Masters as well). Amputation contains the leftovers of a torture-murder scene in the middle of a highway. This is not an accident scene – no effort has been made to assist or remove the body. Importantly, Nerdrum’s paintings show how him to be turning his back on a modernism that had chosen to turn its back on classical style and technique. In Amputation, time (which is both crucial and elusive in reading Nerdum’s work), is told by the presence of twentieth century clothing, an asphalt highway, and the hairstyle of the victim. Nerdrum’s 1970s work showed great promise and it is a promise which he has matched with many exciting and thought provoking works since. Paul Cantor does a wonderful job of describing Nerdrum’s place in the contemporary: “For those who have not seen Nerdrum’s paintings, I try to describe them this way: Imagine the result if Rembrandt had painted the sets of The Road Warrior” (Cantor, 2004).

Nerdrum has since made paintings that the art world has great difficulty dealing with. One of the reasons I think the incredibly artifical term “postmodernism” was embraced by the art world is that it provided it with a place to ghettoize yet absorb (as one more “ism”), a deluge of problematic works from younger artists – an attempt to force into the art world’s conception of the “modern” things which belonged elsewhere. From the point of view of the art world if contemporary painting was allowed to stand as something from a time other than modernism – then modernism would be exposed as having fallen out of time. The enigmatic work by Tibor Csernus is but one other example of this kind of painting that led the art world into many uncomfortable convulsions in its attempt to attach it to modernism under the meaningless label “postmodernism”.

Exactly at the moment many artists were evacuating painting for other forms, Nerdrum not only remained a painter, but one who turned modernism’s logic against itself.

Eighty years earlier painters like the young modernist Picasso had been told they were not producing art because it did not meet the strictures of hegemonic academic classicism. Nerdrum made himself into a painter during a time in which modernism was hegemonic and had long established its message that creativity is the result of an artist turning his/her back on the past. Ironically, when Nerdrum turned his back on the past it was only modernism he put behind him. This is true of many on whom the art world hung the label “post-modernist”. Nerdrum is a non-modernist but fits into the term “postmodern” only in terms of its sense of appropriation from early times.

In the 1980’s Nerdrum settled into what has become his unique style drawing on old master technique and the dedicated study of old master paintings. He is known to stand before old master works in museums (Rembrandt or Caravaggio in particular) for hours memorizing them. He re-presents the mythic light and time that suffuses the Baroque, itself a time of vast social and artistic uncertainty. Nerdrum’s subject matter is not art or using art to simulate art – but rather art in its traditional sense as a simulation of the world – as an attempt to paint a world that we know only as appearances.

This is where illusion plays a strong role in his work. Nerdrum produces the kind of “realism” that is lacking in most contemporary art. Nerdrum’s art (especially the many pieces featuring people with amputations) stands up well to Baudrillard’s claim that “art become a mythic operator…in resolving the monstrosity of the social and of the social order”. Many of Nerdrum’s paintings are of subject matter in a time not far removed from our own. The presence of the rifles in works such as Five persons Around a Water Hole and The Water Protectors bring his subjects startlingly close to our time. Otherwise his work gives few clues to when the scene depicted is taking place. The Night Guard (wearing an early twentieth century leather aviator’s Helmet) or Refugees at Sea (the presence of an automobile tire) tell us that the human figures he paints have passed through some sort of collapse of our contemporary world – while the figures in other of his paintings Initiation, Iron Law and Man With a Horse’s Head could be inhabitants of a world centuries past. The future of civilization is highly contested by the presence of temporal objects in Nerdrum’s work. For me, the overall challenge to the social that Nerdrum continues to pose, weather or not an object appears to link it to a time closer to our own, is that his characters taken as a whole operate in a desert-like landscape where the myth of the social and of humans as social beings has broken down. One thinks of the desert often in looking at Nerdrum’s painting for the desert points to the inhumanity of our asocial and superficial world. The desert is: an ecstatic critique of culture, and ecstatic form of disappearance” (Baudrillard, 1988:5).

Nerdrum’s small groups exist in an environment in which water must be protected, a night guard is necessary, and guns are essential and very present aspects of daily life. The question is unavoidable as to whether these people are the few survivors of a post apocalyptic (post nuclear catastrophe) landscape. It seems that people with remnants of twentieth century technology (guns, lanterns, aviator helmets, tires, and a few articles of the clothing of modernity) – have been hurled by some catastrophe back to a primordial landscape where most of the inhabitants wear animal skins. There is no greenery, little evidence of food – what do Nerdrum’s characters eat? He paints a loaf of bread and a single apple as stand alone works but we never see in his work a grain field from which the ingredients for the bread may have come or a tree that would produce fruit. If we are to demand of art that it challenges (a demand we must make of theory too), it must challenge not only our idea of art, but our idea of the social.

The evil genius of Odd Nerdrum is his ability to make mythic landscapes and monstrous depictions so believable and so easily recognizable as our own after the catastrophe in slow motion which is our society and culture. It seems such a short distance to places very much like Nerdrum’s landscapes as we have witnessed in recent years (Yugoslavia, Darfur, Rwanda). His work vividly reminds us that the horizon of disappearance (of our taken for granted “culture”) rests just beyond our present horizon of social appearances. One also thinks of the death squad culture of Baghdad today. Operating as they do Nerdrum’s paintings challenge us with depictions of a world that is more real than the real by thrusting us forward into world which is at once primordial where initiation rights, raw violence, and survival are the stuff of daily existence. Evil breathes deeply in the atmosphere of an Odd Nerdrum painting. It is this kind of evil which protects us from a proliferation of the “good” – even worse human nightmares of computer modeling, stage managed elections, sound-bite politics, and mall culture. Maybe his work simply tells us that we will fail the great test we are currently undertaking to see if anything human will survive the technical and operational order of cloning, and genetic operationality:

...perhaps we may see this as a kind of adventure, a heroic test: to take the artificialization of living beings as far as possible in order to see, finally, what part of human nature survives the greatest ordeal. If we discover that not everything can be cloned, simulated, programmed, genetically and neurologically managed, then whatever survives could be truly called “human”: some inalienable and indestructible human quality could finally be identified (Baudrillard, 2000:15-16).

III. Anti-dote

And so Odd Nerdrum’s mythic landscapes open a gap in the world of contemporary art and humanist fantasies of cultural permanence or human life without violence. Nerdrum forces us to look closely at the nothingness to which our artifical civilization teeters. It is but one step, he seems to be saying, to the deserts where these human figures occupy a land where almost nothing we take for granted in our contemporary exists. His figures wander the face of a world which is post-culture and certainly post metastatic in the sense of our contemporary cancerous form of globalization by proliferation. As works which represent the more real than real Nerdrum’s paintings participate in a devastating illusion – an illusion of devastation.

Nerdrum’s work explores the illusion of the social and the illusion of endless capitalist globalization. In Nerdrum’s work we are not shown how the machine has broken down but we are confronted with its remnants. To do this Nerdrum creates a scene other than the real – a kind of shock therapy for a society asleep at the wheel. One does not get the impression that Nerdrum has any hope for us avoiding the futures he paints although one never feels he is looking forward to inhabiting these post catastrophic landscapes either. Nerdrum is criticized for what he paints not unlike some of the criticism Baudrillard received for what he wrote – there is a sense among some that Nerdrum and Baudrillard are proponents of catastrophe. Because one paints or writes a particular scenario does not mean that one is in favour of it. Like Baudrillard’s writing, Nerdrum’s painting posits a challenge to go beyond the real – there is no collusion with reality here and no collusion with the art world either.

Nerdrum’s work possesses a sense of deep time – a longing for eternity which is represented by the sunsets which he paints so often. He has written that “he who has seen a glimpse of eternity can offer no contribution to art” (Nerdrum, 2001:107). Nerdrum reminds us that on either side of our monstrous civilization lies a dark abyss. Modernism before Nerdrum seemed merely a tired part of the promotional culture of its time serving up pretty and abstract colours as a form of advertising copy for a metastatic culture – now, after Nerdrum, modernism seems so old and sad (see Cantor, 2004). Nerdrum’s reply to the vehement rejection of his work by modernist critics has been to say that he is no longer producing art. If modernism has captured art and relegated all else to the status of kitsch, then Nerdrum is happy to understand his painting as anti-art, as kitsch:

As soon as I discovered the nature of art and of kitsch, I understood where I belonged. …I have strived to become skillful enough to depict human longing through my kitsch. …Art exists for art itself and addresses the public. Kitsch serves life and addresses the human being (Nerdrum, 2001:1).

Elsewhere he has said:

Kitsch is the opposite of the public space, of the public conversation, of the demand for objectivity and functionality. Kitsch is the intimate space, our selves, our love and our congeniality, our yearnings and our hopes, and our tears, joys and passion. Kitsch comes from the creative person’s private space, and speaks to other private spaces. Kitsch deals therefore with giving intimacy dignity (Nerdrum, 2000).

Nerdrum’s painting then is an anti-art (antidote) for the art world of our time and the promotional culture of which it is a key part. Few painters at the end of the twentieth century were so able to show the art world, by their own example, how much it has lost and what it is not. This assessment applies both to Nerdrum’s old master style and to the stark thoughts his severe images raise about the inhuman ever present just over the horizon of human society. Nerdrum’s painting should be more widely known. I wonder many are willing to work hard enough to deserve it?

- Images above, top: Odd Nerdrum, The Murder of Andreas Baader, oil on canvas, 1978 bottom: Odd Nerdrum Amputation, oil on canvas, 1974.

- Images above, top: Odd Nerdrum, Man With A Horse’s Head, oil on canvas, 1993, bottom: Odd Nerdrum, Pissing Woman, oil on canvas, 1998

1. Jean Baudrillard, America, New York: Verso, 1988.

2. Jean Baudrillard. Paroxysm, Conversations with Philippe Petit, New York: Verso, 1998.

3. Jean Baudrillard, The Vital Illusion, Columbia University Press, 2000.

4. Jean Baudrillard, Impossible Exchange, London: SAGE, 2001.

5.Paul Cantor, “The Importance of Being Odd: Nerdrum’s Challenge to Modernism”, www.artcyclopedia.com

6. Gary Genosko (Editor), The Uncollected Baudrillard, Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE.

7. Alan Jolis, “Odd Man In”, ArtNews, January 1999.

8. Odd Nerdrum, On Kitsch, Oslo: Kagge Forlag, 2001.

9. Odd Nerdrum, ArtNews, April 2000.

Odd Nerdrum

Wikipedia - Odd Nerdrum

All images are courtesy of the artist, all images are copyright of Odd Nerdrum.