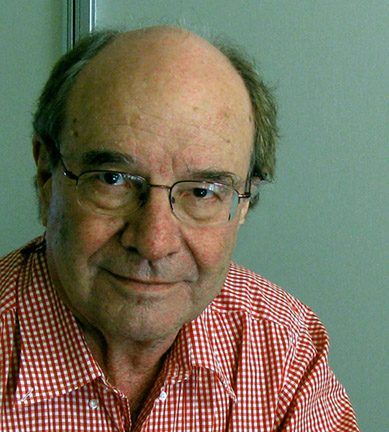

PROFILE: WALLY GILBERT

The polymath is in danger of becoming a dying breed. In days of yore, it was not considered exceptional for the likes of Leonardo da Vinci to whip up masterpieces whilst also investigating profound questions in anatomy and physics. In today's society however, educational courses and career paths have become increasingly specific and specialized, so the idea of scientist, turned businessman, turned artist might seem a strange one. But Nobel-prize winning art photographer, Wally Gilbert personifies that idea. It may be one thing to dabble, but having mastered in physics at world-class institutions, led a successful biotechnology company and turned his hand to successful art photography that has been exhibited across the US and in Europe, Gilbert may be one of the twenty-first century's rare Renaissance men.

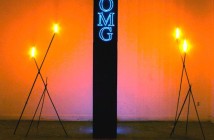

Gilbert’s studio is a riot of color and texture. Dressed in a smart corporate suit, indicative of his flair for business, he describes his technique with digital cameras used to produce the patterns and images, both strange and banal, which that hang from the studio's walls and pillars. It is a small oasis of light and life in the midst of a desolate industrial park in north Somerville. Themes of the cold and the industrial run through some of Gilbert’s digital photography, such as his series of twelve-by-eight-feet extreme close-ups of peeling paint, chain links and rust. These are juxtaposed with luminous images of flowers and decaying fruit, dynamic bullfighters and graceful ballet dancers. A dazzling array of glossy computer screens in the corner of the studio, ablaze with holographic screen-savers, seems to come straight out of a science-fiction movie scene.

The creation and decay of organisms, the power of technology and industry - these are all themes of 77-year-old Gilbert’s long and varied career before he turned to fine-art photography as a profession in 2002. His Nobel Prize, won in 1980, together with Frederick Sanger and Paul Berg for pioneering work in the field of chemistry, was the pinnacle of a career in scientific research that spanned four decades. Even within the realm of science, Gilbert was not bound to one discipline. Gilbert majored in chemistry and physics at Harvard, and mastered theoretical physics at the University of Cambridge in England. In 1960, he returned to Harvard for research and teaching and has been based in Boston, his birthplace, ever since. In the 1970s, he moved onto research in the molecular proteins similar to DNA called RNA, and proposed the RNA world hypothesis for the origins of life, and completed groundbreaking work on the genetic control of protein products.

Gilbert's interests have constantly evolved, shifted gears or completely changed over the years. "It's a very common but deleterious conception that one has to train in one particular thing and then stick with that for the rest of one's life,” he says. “You shouldn't be constrained in this way: it's wildly wrong and very dangerous.”

Gilbert decided to close his lab down because he felt he could no longer embark upon genuinely creative research. After running BioGen, a biotechnology company throughout the 1980s, Gilbert decided to channel his creative energies into digital photography.

"Of course, research is an ongoing theme. One completes a set of problems, but a lot of problems are still left unsolved. Nobel Prize winners are always looking for an encore, and driven by desire to repeat," says Gilbert.

Gilbert, however, seems exempt from such desires and pursued photography instead of another prize. In 2002, he discovered he could take large photographs, starting at two by four feet, using very small cameras. He was drawn to the different emotional effects that pixellation and lighting can create.

"Playing with a camera has sort of been a lifelong hobby on one level and I took it as seriously as you can take a hobby, " says Gilbert, who has no formal training in photography. An auto-didactic, Gilbert gave up teaching others to teach himself the visual discipline. Armed initially with only a "general interest in art as an observer," Gilbert claims his prior experiences helped him in his approach to photography. "As someone who was an experimental scientist, technical things like Photoshop were not a barrier for me to try anything," he says.

Gilbert likes to stick to simple devices, using very small cameras with as few as two mega-pixels to create large, mostly unfocused pictures which achieve a soft, hazy and often dreamlike effect. His interest in molecular science is apparent in the granular effects of his close-up shots of inanimate objects, emphasizing texture and color.

A new challenge arose when Boston Globe arts writer Christine Temin invited Gilbert to photograph the Boston Ballet Company for a book she was writing. The small, basic cameras that Gilbert preferred were not sufficient to capture the complex light and motion that dance photography requires. Another challenge came in trying not to turn the photograph series into reportage. "I like to photograph, but not to record," says Gilbert. His 'art's for art's sake' philosophy seems to jar with his former career in research. He takes a specific approach when it comes to his subjects: “I go in seeking some notion of beauty that is not conventional, it can be found in form and texture," says Gilbert.

Gilbert overcame these challenges however to produce Boston Ballet and Beyond, a photographic essay, which was exhibited at the Schomburg Gallery in California earlier this year. Gilbert prefers experimenting with color- isolation, form and texture to conventional 'beauty' shots added to the Boston Ballet series by creating color-blocks of the ballet dancers' silhouettes

Creativity is the lifeblood of Gilbert’s career moves, in art and in the less obvious realms of science and business. He has moved from the lab, to the business boardroom and now to the art studio. In addition to his photography, he remains a venture capitalist with stakes in several biotechnology companies. As he says, "Both art and science involve personal creation - new knowledge in one sense and new ideas or emotions in the other. The general interest is where can I find something that is novel and will affect the world, or affect the individual.”

"I have a strongly visual component in all my work. When I conduct experiments, I see them in visual terms rather than purely symbolic, abstract terms. These are the underlying themes of my work so far."

- Wally Gilbert: physicist, biochemist, Nobel laureate and photographer.

- Image of Gilbert’s studio in Somerville’s Brickbottom district by Chris Devers. CC-licensed photo acquired on Flickr.

- Wally Gilbert, Boston Ballet #14F, Tutu and bodice for Raymonda, Act III, Kodak Print, Face-mounted on Plexiglas. Image courtesy of the artist and Schomburg Gallery, Santa Monica, CA.

Wally Gilbert's work on Artspan.

Gilbert's page on Somerville's Brickbottom Artist Association's website.

"Fresh Fruit," a two person exhibit with Gilbert and sculptor Stephanie Chubbuck, is on view through July 2009 at the Mayyim Hayyim Gallery in Newton, Mass.