FAITH AND THE SALE OF ART

One of the many side-effects of a bursting economic bubble is the revealing of the nature of the shady deals and shaky business models that seem so infallible when money is easy. Ponzi schemes collapse, risky investments fail, and unstable business practices become obvious and suspicious. The art world, and its recent bubble are no exception, and much ink has been spilled over the flaws in the system, the necessary market contractions, and the people who believed in and supported the whole house of cards.

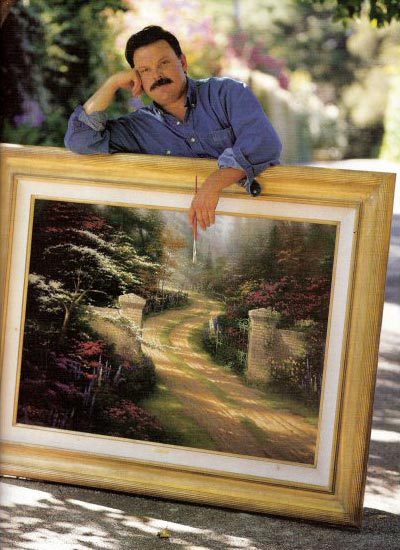

The sale of art as investment has always been somewhat predicated on a kind of faith -- faith in the expanding value of the art market, faith in the career of the artist, faith in the reputation of the dealer, and so on. But it is faith of a different kind, the religious kind, that motivates the sale of Thomas Kinkade's paintings and, apparently, how his company negotiates with potential dealers.

On June 18, 2009, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that a Federal appeals court had "restored an arbitration panel's $2.1 million award to two former gallery owners who say Kinkade's company duped them into investing their life's savings in a doomed enterprise." The story, as presented in the article, reveals that Kinkade's business model included the exploitation of the religious faith of potential dealers to encourage them to invest in his paintings.

In their lawsuit, Hazlewood and Spinello, former San Ramon residents who operated their art galleries in Virginia and were married at the time, said the company had exploited their faith to reel them in.

At a weeklong presentation for prospective Kinkade Signature Gallery owners, company executives "said they would support us as partners in spreading the light," Spinello said at the time of the arbitration award. "They said their business was blessed."

Thomas Kinkade, who bills himself as "The Painter of Light," is not generally considered an important figure in the art world, despite the scale of his business and the amount of work he sells each year. This is partially due to the Christian themes in his work, as well has his sales model directed at a decidedly non-art-world audience. The SF Chronicle politely says that is paintings "have been far more popular with the public than with art critics." It is not Kinkade's relationship to the art world that is at issue here, though, and at the core of the case, says Felix Salmon, is the fact that "Kinkade is more of a bad businessman than an evil one."

The people who ran Kinkade stores are upset at him, because he acted a bit like Chrysler towards dealers it ended up closing: Kinkade forced the dealers to buy expensive inventory which simply didn’t sell, and refused to accept returns unless they were accompanied by orders for three times as much art as was being returned. Obviously, it was hard for the shops to make money in such circumstances. But I get the feeling they’re missing the forest for the trees: they weren’t losing money because of the decisions being made by Kinkade’s company, so much as they were losing money because they’d hitched their wagon to a company which was in a tailspin.

Over at Pandagon, Amanda Marcotte addressed the part of this that is more interesting, and more revealing, by considering how people's faith was exploited to make money. She sums up:

I wouldn’t be surprised if this sort of thing is all over the evangelical community, because they do have their own economy of Jesus gear and half-baked entrepreneurial projects. In the past, I tended to think most of the Jesus gear stuff, from Jesus T-shirts to Christian rock, was pretty harmless, but now I’m not so sure. All these products need distributors, and since most of them rely heavily on word-of-mouth and church-based marketing, there’s a lot of room for exploitation there.

There are a number of parallels here to the art fair boom that is now going bust. Artists, and their dealers, sell work based on an artificial inflation of value, that is predicated on a number of articles of faith (some of which I listed above). The gallery system is designed to create this market value for work that far exceeds the usual methods of valuing a product, which include material costs, labor, marketing and some profit margin.1 The perpetuation of this idea, this article of faith among collectors and investors, that a work of art has a value that will increase over time, is the life-blood of the art market. The intrusion of anything that undermined that faith would be a real blow to the short-term, if not long-term, perpetuation of an art market bubble.

Yet, I would argue that the rise of the art fairs did just that, by flattening the hierarchies within the market and creating a sense of commodity around the art on view. Where the gallery system thrives on the prestige of the dealers and the very status of the art as being better than a commodity, more valuable and important, this new model required that the whole prestige system be unraveled. For this reason, a number of galleries sought out artists whose work was marketable in a fair context, but which might not survive in the larger gallery system. This is only to say that the work was more accessible in the art-saturated environment of the fairs, and not to devalue the work or the artists. However, it is very telling that many galleries fostered artists specifically for the fairs, while maintaining a separate roster for solo shows in their galleries.

The long term effects of this may be negligible, but in the short term it is already pretty clear that the genie is hard to put back in the bottle, and that the audiences fostered at the art fairs will not easily transition from the commodity-based market of the fair to the prestige-based system of the galleries. The big ticket art, the kind of work that all galleries hope to move, requires faith on the part of the collector that the art surpasses its status as a commodity and will endure as a meaningful and valuable object far into the future. Undermining that faith through art fairs, cut-rate prices, and other subtle signals that the prestige of the work might be compromised, make it harder to sell the work.

In many ways, the story of Thomas Kinkade's creation of a market based on religious faith, and the idea that the galleries of his dealers were "blessed," is not too far from some of the faith required to support the kind of art world bubble we just witnessed. Kinkade's market is probably more stable, in fact, because while the market downturn may undercut his profits, his audience will always have their faith. In the art world, the two are far more interdependent, and small changes in one can have a drastic impact on the other. The current shifts in the art market, necessitated by the economic downturn, may signal some long-term changes in how art is valued and sold and it appears that some of these changes will be based in the new perceptions of art fostered during the bubble years by galleries hoping to make quick money. The market will rebound, as it always does, but how artists and their work become valued, and the willingness of collectors to continue the faith-based system, remains to be seen.

- Thomas Kinkade, the Painter of Ligh

- Thomas Kinkade, I’ll Be Home For Christmas

- Thomas Kinkade, The Good Shepard’s Cabin

1 - It could be argued here that the gallery system itself is a giant marketing operation, and thus the marketing costs are exponentially larger than for most other products, however I think that argument only stretches so far when considering the sale prices of many artists.

Thomas Kinkade's website

San Francisco Chronicle: Artist's firm on hook for $2.1 million by Bob Egelko

Pandagon: The Broken Ethics of the Evangelical Economy by Amanda Marcotte

Images found online here, here and here.