In the best of all possible worlds, perhaps in the not distant future, Raymond Liddell will purchase a house in Tuscany where he hopes to reread all of the Greek and Roman classics, in the original. And to wander through ancient ruins with Pausanias’s 2nd century A.D. “Description of Greece” in hand while romancing the stones.

Between now and then, however, there is a lot on his plate including teaching the classics and art history at Emerson College and the Art Institute of Boston as well as a recent appointment as Contributing Editor to Art New England. He was brought into the publication by Ellen Howards who is fairly new to the position of Editor in Chief. Previously she was an editor of the former Arts Media. As is often the case when a new editor is installed they come with people they are used to working with and there are housekeeping and staff changes. Liddell expects to have a consulting role as the bimonthly art publication undergoes changes initiated to correct the declining circulation and ad revenue of the past few years which came with new ownership and editorial direction. In the December/ January issue in its annual disclosure statement the publication stated a press run of some 10,000 copies.

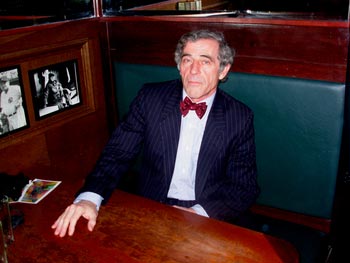

As we met over a beer and burger covering a range of issues and highlights of his personal history the lmits of an audience for arts writing was a topic of discussion. He asked rhetorically just how large the potential readership might be? And how a publication might grow its audience by covering more relevant issues? Frankly, for the past few years, after leaving a long association as a columnist, I have not felt a compelling urge to keep up with its content. So I will follow with renewed interest how ANE progresses in its coming issues. In general, it takes several issues for a new editor to make a significant impact. There is the challenge of recruiting writers as well as the brain storming involved with editorial direction and policy.

In the last issue, Liddell covered the blog phenomenon in arts writing and interviewed me for the piece. By the time the article appeared I was surprised at how low were the circulation figures I stated. Since that interview last fall the readership has grown steadily and in January the combined visitors to Maverick/ Berkshire Fine Arts reached 9,500 which is about equal to the bimonthly press run of ANE. But Raymond pointed out that to make a comparison is a matter of apples and oranges. That ANE reflects the business plan of a for profit publication and the art blogs such as mine or Big Red and Shiny (which has a circulation between 12,000 and 15,000 monthly) are primarily artist run labors of love which generate little or no revenue. At least for now the model of print media remains although it is widely observed to be in decline next to the change of habit of people seeking information on line.

Just how did Lidell arrive at this interesting juncture? Actually,through a fascinating and circuitous route. He grew up in Cambridge, Mass. but attended Phillips Academy in Andover before earning a bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Harvard in 1968. Some of the interesting students he recalls from that time were involved, as he was, with the Loeb Drama Center including John Lithgow, Tommy Lee Jones and Stockard Channing. “I acted and worked on tech and lighting at the Loeb” he said. “That was before Robert Brustein’s American Repertory Theatre took over. When I was a student we had productions on the main stage and students were not happy when they were replaced by a professional company.”

Just where did art come in I asked? At that time the visual arts were viewed as electives taught at the Carpenter Center housed in Le Corbusier’s only American building. “ I took courses in still photography and animation from Derek Lamb. He is familiar as the animator of the Ed Gorey sequence that opens Mystery Theatre for PBS. At Harvard one could major in art history but not in studio art.

“After Harvard I worked for four months on a dig in Turkey,” he said. “I was a field photographer for the excavation at Sardis. This is when I fell in love with archaeology. But it was inevitable that I would eventually be drafted so I cut a deal and joined the Navy where I went to film school to become a combat cinematographer. I was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet Combat Camera Group. We were a mobile unit and focused on shooting news footage. The group was founded by Edward Steichen during World War Two. I greatly respect his work. He had a long and significant career in the Navy. Steichen brought them up to speed in such areas as aerial surveilance, documentary, and spy photography. I did that for four years until 1972. In 1971, I was named the Department of Defense News Film Photographer of the Year.”

With that background and training one assumes that he was destined for a career as a cinematographer. But in the course of lugging around heavy shoulder held cameras with a double battery belt, he suffered spinal trauma which put an end to any ambition of continuing as a “shooter.”

Following being mustered out of the Navy he enrolled as a special student in the classics at Harvard. Over the next three years he studied intensive Greek and German to prepare for a doctoral program in Classical art. He went on to four years of study at Bryn Mawr under the renowned authority on Ancient Greek sculpture, Dr. Brunhilde Ridgeway. He earned a Master’s degree but before undertaking to write a dissertation he was given an offer he could not refuse.

He left graduate school in the Classics to become the second adminsitrative director of the Museum of Broadcasting which was then located at 1 East 53rd street next to the Museum of Modern Art. It has since expanded and is located near CBS on West 54th Street. Now there is also a branch of the Museum in Los Angeles. He describes the museum as having the “world’s largest collection of TV and Radio tapes. It is a destination for scholars as well as having great public access to the collection. They put on exhibitions and publish monographs in the field.”

Just how did such an opportunity come seemingly out of the blue? “When I was a graduate student at Harvard I was hired as a Teaching Assistant for an undergraduate course on the History of Media, from Guttenberg to Television,” he explained. “It was taught by Robert Saudek who was a producer in the early days of broadcasting. Do you recall a show called ‘Omnibus’ which was hosted by Alistair Cook? He produced that show and knew Cook who frequently came to Cambridge to lecture as a part of the course.”

Liddell recalls many a pleasant occasion spent with Saudek, Cook and the Master of the House when he visited Cambridge. “He was a born story teller” Liddell recalled adding that there were usually free flowing spirits to stoke the spirited conversation. “Cook was a wonderful and charming man just like you saw him on TV as host of Masterpiece Theatre. But much funnier in real life. Later William S. Paley (President of CBS) asked Saudek to found the Museum of Broadcasting which he also funded very generously. Years later Saudek asked me to take over. I spent three years there before receiving another offer I could not refuse. To join the Brooklyn Museum as Vice Director for three years. Then came the offer to be executive director of the Archaeological Institute of America which I did for the next two and a half years. By then I had it with running big organizations.”

The money and prestige of running major instititions in New York City lost its charm. These positions he describes as entailing 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. Most of all he regretted being on the administrative rather than the creative side of museums. “The curators get to plan and research exhibitions which is the fun part” he explained. “And I had to find a way to pay for it.” But having spent all those years in administration he felt it was too late to go back to finish graduate study. Instead he pursued independent consulting discovering that he could do quite well advising on development and fund raising and not be chained to a desk. Today he describes himself as “semi retired” is debt free and “ I never use a credit card except when traveling.” So he is that rare individual who gets to do what pleases and interests him. He regrets that he didn’t start teaching sooner.

“I teach Greek and Roman history and literature in translation at Emerson College” he said. Interestingly Emerson specialises in performance and broadcasting.

Considering that could be a tough and demanding course I asked how students respond. “They like it” he said. “For example we started reading the Odyssey and I showed them how easy it was to translate the opening lines from Greek to English. They were very responsive and some even expressed being interested in studying Greek.”

More importantly teaching the classics is a way of coming back to his first love. “I didn’t go to graduate school to be an administrator.” Clearly he is enjoying life more fully having distanced himself from such responsibilities. I asked how he had gotten into writing journalism and arts criticism. It started by free lancing for the Essex Country Newspapers on the North Shore of Boston including the Gloucester Times, where he lived for many years until relocating to inner Boston, the Salem Evening News, and the Newburyport Times. He was fortunate to work with a good editor and got to write a range of features, travel pieces, restaurant reviews and arts coverage. Along the way he wrote for the old Arts Media where Howards was an editor.

With an extensive background in arts adminsitration, development and fundraising I asked for his views of the emergence of the new Institute of Contemporary Art and its 60,000 square foot new waterfront venue? Actually it is a topic we have discussed on a number of occasions both on and off the record. Overall, he has questions but takes a wait and see approach. It will be more than a year before there is a financial report filed with the Charity Desk of the Attorney General’s office. I have spent many a session looking into those documents and it takes care and a critical eye to deconstruct the raw figures into a larger context and overview.

“We (journalists) can ask them questions but they are not obliged to give answers” he said. In fact since its relocation the media requests at the ICA have so greatly increased that it has become ever more challenging to get through to them with even routine requests for press access to events let alone any serious reporting. With the current barrage of coverage, mostly euphoric hype, the ICA can be selective about whose calls to return.

As a writer and editor of Art New England surely there is much he would like to know on behalf of the publication and its readers. So active journalists covering the same material and events can get a bit dodgy about giving straight up information and clues to a colleague pursuing the same potential story. But he offered generic comments and observations.

“You and I have already talked about what we consider the squandered space in the lobby area” he said. “Has the euphoria started to die down? Are there any figures available about actual day to day attendance? Just what are the target goals for attendance and box office revenue to service debt? There are questions that cannot be answered without touring the non public spaces of the museum. If they are developing a permanent collection just what space and facilities have been provided to store and conserve the work? There is just no way of telling.”

Right now the ICA doesn’t appear to “need” the media. They have been on the receiving end of numerous puff pieces stating that director Jill Medvedow has pulled off a “miracle” in a community where contemporary art has received little tangible support. While it has been reported that she raised some $60 million has any journalist had access to the books? How much of that, for example, was gifted and how much borrowed? When and if the ICA starts to feel “pinched” in reaching its attendance target and revenues, which seems inevitable considering the scale and risk of this venture, perhaps it will be more “accessible” to the media. There was many a long stretch in the history of the ICA when it got by on the “kindness of strangers.” Usually that meant Boston’s artists who were often asked to donate their works for fundraising drives. When museums such as the ICA and Rose, for example, had small budgets for exhibitions they tended to rely more on “local art.”

But as Liddell aptly comments we will have to take a wait and see approach as these issues play out. While on the other end of town Malcolm Rogers moves forward with building and expansion plans for the Museum of Fine Arts which are at least triple the critical mass and scale of intensity of those that were faced by the ICA. Then there is the Big Dig which many prefer to view as the Big Mess. So there will be lots to chew on the next time we chow down with a brewskie.

All images are courtesy of the author.